Princess Olga, baptized Elena. Born approx. 920 - died July 11, 969. The princess who ruled the Old Russian state from 945 to 960 after the death of her husband, Prince of Kyiv Igor Rurikovich. The first of the rulers of Rus' accepted Christianity even before the baptism of Rus'. Holy Equal-to-the-Apostles of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Princess Olga was born ca. 920

The chronicles do not report Olga's year of birth, but the later Degree Book reports that she died at the age of about 80, which places her date of birth at the end of the 9th century. The approximate date of her birth is reported by the late “Arkhangelsk Chronicler”, who reports that Olga was 10 years old at the time of her marriage. Based on this, many scientists (M. Karamzin, L. Morozova, L. Voitovich) calculated her date of birth - 893.

The life of the princess states that her age at the time of death was 75 years. Thus Olga was born in 894. True, this date is called into question by the date of birth of Olga’s eldest son, Svyatoslav (around 938-943), since Olga should have been 45-50 years old at the time of her son’s birth, which seems incredible.

Considering the fact that Svyatoslav Igorevich was Olga’s eldest son, Boris Rybakov, taking 942 as the prince’s date of birth, considered the year 927-928 to be the latest point of Olga’s birth. A similar opinion (925-928) was shared by Andrei Bogdanov in his book “Princess Olga. Holy warrior."

Alexey Karpov in his monograph “Princess Olga” makes Olga older, claiming that the princess was born around 920. Consequently, the date around 925 seems more correct than 890, since Olga herself in the chronicles for 946-955 appears young and energetic, and gives birth to her eldest son around 940.

According to the earliest ancient Russian chronicle, “The Tale of Bygone Years,” Olga was from Pskov (Old Russian: Pleskov, Plskov). The life of the holy Grand Duchess Olga specifies that she was born in the village of Vybuty in the Pskov land, 12 km from Pskov up the Velikaya River. The names of Olga’s parents have not been preserved; according to the Life, they were of humble birth. According to scientists, Varangian origin is confirmed by her name, which has a correspondence in Old Norse as Helga. The presence of presumably Scandinavians in those places is noted by a number of archaeological finds, possibly dating back to the first half of the 10th century. The ancient Czech name is also known Olha.

The typographical chronicle (end of the 15th century) and the later Piskarevsky chronicler convey a rumor that Olga was the daughter of the Prophetic Oleg, who began to rule Russia as the guardian of the young Igor, the son of Rurik: “Nitsyi say, ‘Yolga’s daughter is Yolga’.” Oleg married Igor and Olga.

The so-called Joachim Chronicle, the reliability of which is questioned by historians, reports Olga’s noble Slavic origins: “When Igor matured, Oleg married him, gave him a wife from Izborsk, the Gostomyslov family, who was called Beautiful, and Oleg renamed her and named her Olga. Igor later had other wives, but because of her wisdom he honored Olga more than others.”.

If you believe this source, it turns out that the princess renamed herself from Prekrasa to Olga, taking a new name in honor of Prince Oleg (Olga is the female version of this name).

Bulgarian historians also put forward a version about the Bulgarian roots of Princess Olga, relying mainly on the message of the “New Vladimir Chronicler”: “Igor got married [Ѻlg] in Bulgaria, and princess Ylga sings for him”. And translating the chronicle name Pleskov not as Pskov, but as Pliska - the Bulgarian capital of that time. The names of both cities actually coincide in the Old Slavic transcription of some texts, which served as the basis for the author of the “New Vladimir Chronicler” to translate the message in the “Tale of Bygone Years” about Olga from Pskov as Olga from the Bulgarians, since the spelling Pleskov to designate Pskov has long gone out of use .

Statements about the origin of Olga from the annalistic Carpathian Plesnesk, a huge settlement (VII-VIII centuries - 10-12 hectares, before the 10th century - 160 hectares, before the 13th century - 300 hectares) with Scandinavian and West Slavic materials are based on local legends.

Marriage to Igor

According to the Tale of Bygone Years, the Prophetic Oleg married Igor Rurikovich, who began to rule independently in 912, to Olga in 903, that is, when she was already 12 years old. This date is questioned, since, according to the Ipatiev list of the same “Tale,” their son Svyatoslav was born only in 942.

Perhaps to resolve this contradiction, the later Ustyug Chronicle and the Novgorod Chronicle, according to the list of P. P. Dubrovsky, report Olga’s age of ten at the time of the wedding. This message contradicts the legend set out in the Degree Book (second half of the 16th century), about a chance meeting with Igor at a crossing near Pskov. The prince hunted in those places. While crossing the river by boat, he noticed that the carrier was a young girl dressed in men's clothing. Igor immediately “flared with desire” and began to pester her, but received a worthy rebuke in response: “Why do you embarrass me, prince, with immodest words? I may be young and humble, and alone here, but know: it is better for me to throw myself into the river than to endure reproach.” Igor remembered about the chance acquaintance when the time came to look for a bride, and sent Oleg for the girl he loved, not wanting any other wife.

The Novgorod First Chronicle of the younger edition, which contains in the most unchanged form information from the Initial Code of the 11th century, leaves the message about Igor’s marriage to Olga undated, that is, the earliest Old Russian chroniclers had no information about the date of the wedding. It is likely that the year 903 in the PVL text arose at a later time, when the monk Nestor tried to bring the initial ancient Russian history into chronological order. After the wedding, Olga’s name is mentioned again only 40 years later, in the Russian-Byzantine treaty of 944.

According to the chronicle, in 945, Prince Igor died at the hands of the Drevlyans after repeatedly collecting tribute from them. The heir to the throne, Svyatoslav, was only three years old at that time, so Olga became the de facto ruler of Rus' in 945. Igor's squad obeyed her, recognizing Olga as the representative of the legitimate heir to the throne. The decisive course of action of the princess in relation to the Drevlyans could also sway the warriors in her favor.

After the murder of Igor, the Drevlyans sent matchmakers to his widow Olga to invite her to marry their prince Mal. The princess successively dealt with the elders of the Drevlyans, and then brought their people into submission. The Old Russian chronicler describes in detail Olga’s revenge for the death of her husband:

First revenge:

The matchmakers, 20 Drevlyans, arrived in a boat, which the Kievans carried and threw into a deep hole in the courtyard of Olga's tower. The matchmaker-ambassadors were buried alive along with the boat.

“And, bending towards the pit, Olga asked them: “Is honor good for you?” They answered: “Igor’s death is worse for us.” And she ordered them to be buried alive; and they fell asleep,” says the chronicler.

Second revenge:

Olga asked, out of respect, to send new ambassadors from the best men to her, which the Drevlyans willingly did. An embassy of noble Drevlyans was burned in a bathhouse while they were washing themselves in preparation for a meeting with the princess.

Third revenge:

The princess and a small retinue came to the lands of the Drevlyans to celebrate a funeral feast at her husband’s grave, according to custom. Having drunk the Drevlyans during the funeral feast, Olga ordered them to be chopped down. The chronicle reports five thousand Drevlyans killed.

Fourth revenge:

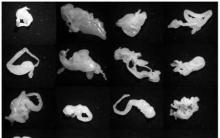

In 946, Olga went with an army on a campaign against the Drevlyans. According to the First Novgorod Chronicle, the Kyiv squad defeated the Drevlyans in battle. Olga walked through the Drevlyansky land, established tributes and taxes, and then returned to Kyiv. In the Tale of Bygone Years (PVL), the chronicler made an insert into the text of the Initial Code about the siege of the Drevlyan capital of Iskorosten. According to the PVL, after an unsuccessful siege during the summer, Olga burned the city with the help of birds, to whose feet she ordered lit tow with sulfur to be tied. Some of the defenders of Iskorosten were killed, the rest submitted. A similar legend about the burning of the city with the help of birds is also told by Saxo Grammaticus (12th century) in his compilation of oral Danish legends about the exploits of the Vikings and the skald Snorri Sturluson.

After the reprisal against the Drevlyans, Olga began to rule Russia until Svyatoslav came of age, but even after that she remained the de facto ruler, since her son spent most of his time on military campaigns and did not pay attention to governing the state.

Olga's reign

Having conquered the Drevlyans, Olga in 947 went to the Novgorod and Pskov lands, assigning lessons (tribute) there, after which she returned to her son Svyatoslav in Kyiv.

Olga established a system of “cemeteries” - centers of trade and exchange, in which taxes were collected in a more orderly manner; Then they began to build churches in graveyards. Olga’s journey to the Novgorod land was questioned by Archimandrite Leonid (Kavelin), A. Shakhmatov (in particular, he pointed out the confusion of the Drevlyansky land with the Derevskaya Pyatina), M. Grushevsky, D. Likhachev. The attempts of Novgorod chroniclers to attract unusual events to the Novgorod land were also noted by V. Tatishchev. The chronicle's evidence of Olga's sleigh, allegedly kept in Pleskov (Pskov) after Olga's trip to the Novgorod land, is also critically assessed.

Princess Olga laid the foundation for stone urban planning in Rus' (the first stone buildings of Kyiv - the city palace and Olga's country tower), and paid attention to the improvement of the lands subject to Kyiv - Novgorod, Pskov, located along the Desna River, etc.

In 945, Olga established the size of the “polyudya” - taxes in favor of Kyiv, the timing and frequency of their payment - “rents” and “charters”. The lands subject to Kyiv were divided into administrative units, in each of which a princely administrator, a tiun, was appointed.

Konstantin Porphyrogenitus, in his essay “On the Administration of the Empire,” written in 949, mentions that “the monoxyls coming from external Russia to Constantinople are one of Nemogard, in which Sfendoslav, the son of Ingor, the archon of Russia, sat.” From this short message it follows that by 949 Igor held power in Kyiv, or, which seems unlikely, Olga left her son to represent power in the northern part of her state. It is also possible that Constantine had information from unreliable or outdated sources.

Olga’s next act, noted in the PVL, is her baptism in 955 in Constantinople. Upon returning to Kyiv, Olga, who took the name Elena in baptism, tried to introduce Svyatoslav to Christianity, but “he did not even think of listening to this. But if someone was going to be baptized, he did not forbid it, but only mocked him.” Moreover, Svyatoslav was angry with his mother for her persuasion, fearing to lose the respect of the squad.

In 957, Olga paid an official visit to Constantinople with a large embassy, known from the description of court ceremonies by Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus in his essay “On Ceremonies.” The Emperor calls Olga the ruler (archontissa) of Rus', the name of Svyatoslav (in the list of retinue the “people of Svyatoslav” are indicated) is mentioned without a title. Apparently, the visit to Byzantium did not bring the desired results, since PVL reports Olga's cold attitude towards the Byzantine ambassadors in Kyiv shortly after the visit. On the other hand, Theophanes' Successor, in his story about the reconquest of Crete from the Arabs under Emperor Roman II (959-963), mentioned the Rus as part of the Byzantine army.

It is not known exactly when Svyatoslav began to rule independently. PVL reports his first military campaign in 964. The Western European chronicle of the Successor of Reginon reports under 959: “They came to the king (Otto I the Great), as it later turned out to be a lie, the ambassadors of Helena, Queen of Rugov, who was baptized in Constantinople under the Emperor of Constantinople Romanus, and asked to consecrate a bishop and priests for this people.”.

Thus, in 959 Olga, baptized Elena, was officially considered the ruler of Rus'. The remains of a 10th-century rotunda, discovered by archaeologists within the so-called “city of Kiya,” are considered material evidence of the stay of Adalbert’s mission in Kyiv.

The convinced pagan Svyatoslav Igorevich turned 18 years old in 960, and the mission sent by Otto I to Kyiv failed, as the Continuer of Reginon reports: “962 year. This year Adalbert returned back, having been appointed bishop of Rugam, because he did not succeed in anything for which he was sent, and saw his efforts in vain; on the way back, some of his companions were killed, but he himself barely escaped with great difficulty.”.

The date of the beginning of Svyatoslav’s independent reign is quite arbitrary; Russian chronicles consider him to be the successor to the throne immediately after the murder of his father Igor by the Drevlyans. Svyatoslav was constantly on military campaigns against the neighbors of Rus', entrusting the management of the state to his mother. When the Pechenegs first raided the Russian lands in 968, Olga and Svyatoslav’s children locked themselves in Kyiv.

Having returned from the campaign against Bulgaria, Svyatoslav lifted the siege, but did not want to stay in Kyiv for long. When the next year he was about to go back to Pereyaslavets, Olga restrained him: “You see, I’m sick; where do you want to go from me? - because she was already sick. And she said: “When you bury me, go wherever you want.”.

Three days later, Olga died, and her son, and her grandchildren, and all the people cried for her with great tears, and they carried her and buried her in the chosen place, Olga bequeathed not to perform funeral feasts for her, since she had a priest with her - he and buried blessed Olga.

The monk Jacob, in the 11th century work “Memory and Praise to the Russian Prince Volodymer,” reports the exact date of Olga’s death: July 11, 969.

Olga's baptism

Princess Olga became the first ruler of Rus' to be baptized, although both the squad and the Russian people under her were pagan. Olga’s son, the Grand Duke of Kiev Svyatoslav Igorevich, also remained in paganism.

The date and circumstances of the baptism remain unclear. According to the PVL, this happened in 955 in Constantinople, Olga was personally baptized by Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus with the Patriarch (Theophylact): “And she was given the name Elena in baptism, just like the ancient queen-mother of Emperor Constantine I.”.

PVL and the Life decorate the circumstances of the baptism with the story of how the wise Olga outwitted the Byzantine king. He, marveling at her intelligence and beauty, wanted to take Olga as his wife, but the princess rejected the claims, noting that it was not appropriate for Christians to marry pagans. It was then that the king and the patriarch baptized her. When the tsar again began to harass the princess, she pointed out that she was now the tsar’s goddaughter. Then he richly presented her and sent her home.

From Byzantine sources only one visit of Olga to Constantinople is known. Konstantin Porphyrogenitus described it in detail in his essay “On Ceremonies”, without indicating the year of the event. But he indicated the dates of official receptions: Wednesday, September 9 (on the occasion of Olga’s arrival) and Sunday, October 18. This combination corresponds to 957 and 946 years. Olga's long stay in Constantinople is noteworthy. When describing the technique, the name is basileus (Konstantin Porphyrogenitus himself) and Roman - basileus Porphyrogenitus. It is known that Roman II the Younger, the son of Constantine, became his father's formal co-ruler in 945. The mention at the reception of Roman's children testifies in favor of 957, which is considered the generally accepted date for Olga's visit and her baptism.

However, Konstantin never mentioned Olga’s baptism, nor did he mention the purpose of her visit. A certain priest Gregory was named in the princess’s retinue, on the basis of which some historians (in particular, Academician Boris Alexandrovich Rybakov) suggest that Olga visited Constantinople already baptized. In this case, the question arises why Constantine calls the princess by her pagan name, and not Helen, as the Successor of Reginon did. Another, later Byzantine source (11th century) reports baptism precisely in the 950s: “And the wife of the Russian archon, who once set sail against the Romans, named Elga, when her husband died, arrived in Constantinople. Baptized and having openly made a choice in favor of the true faith, she, having received great honor for this choice, returned home.”.

The successor of Reginon, quoted above, also speaks about baptism in Constantinople, and the mention of the name of Emperor Romanus testifies in favor of baptism in 957. The testimony of the Continuer of Reginon can be considered reliable, since, as historians believe, Bishop Adalbert of Magdeburg, who led the unsuccessful mission to Kyiv, wrote under this name (961) and had first-hand information.

According to most sources, Princess Olga was baptized in Constantinople in the fall of 957, and she was probably baptized by Romanos II, son and co-ruler of Emperor Constantine VII, and Patriarch Polyeuctus. Olga made the decision to accept the faith in advance, although the chronicle legend presents this decision as spontaneous. Nothing is known about those people who spread Christianity in Rus'. Perhaps these were Bulgarian Slavs (Bulgaria was baptized in 865), since the influence of Bulgarian vocabulary can be traced in the early ancient Russian chronicle texts. The penetration of Christianity into Kievan Rus is evidenced by the mention of the cathedral church of Elijah the Prophet in Kyiv in the Russian-Byzantine treaty (944).

Olga was buried in the ground (969) according to Christian rites. Her grandson, Prince Vladimir I Svyatoslavich, transferred (1007) the relics of saints, including Olga, to the Church of the Holy Mother of God in Kyiv, which he founded. According to the Life and the monk Jacob, the body of the blessed princess was preserved from decay. Her “shining like the sun” body could be observed through a window in the stone coffin, which was opened slightly for any true believer Christian, and many found healing there. All the others saw only the coffin.

Most likely, during the reign of Yaropolk (972-978), Princess Olga began to be revered as a saint. This is evidenced by the transfer of her relics to the church and the description of miracles given by the monk Jacob in the 11th century. Since that time, the day of remembrance of Saint Olga (Elena) began to be celebrated on July 11, at least in the Tithe Church itself. However, official canonization (churchwide glorification) apparently occurred later - until the middle of the 13th century. Her name early becomes baptismal, in particular among the Czechs.

In 1547, Olga was canonized as Saint Equal to the Apostles. Only five other holy women in Christian history have received such an honor (Mary Magdalene, First Martyr Thekla, Martyr Apphia, Queen Helen Equal to the Apostles and Nina, the enlightener of Georgia).

The memory of Equal-to-the-Apostles Olga is celebrated by Orthodox churches of the Russian tradition on July 11 according to the Julian calendar; Catholic and other Western churches - July 24 Gregorian.

She is revered as the patroness of widows and new Christians.

Princess Olga (documentary film)

Memory of Olga

In Pskov there is the Olginskaya embankment, the Olginsky bridge, the Olginsky chapel, as well as two monuments to the princess.

From the time of Olga until 1944, there was a churchyard and the village of Olgin Krest on the Narva River.

Monuments to Princess Olga were erected in Kyiv, Pskov and the city of Korosten. The figure of Princess Olga is present on the monument “Millennium of Russia” in Veliky Novgorod.

Olga Bay in the Sea of Japan is named in honor of Princess Olga.

The urban-type settlement Olga, Primorsky Territory, is named in honor of Princess Olga.

Olginskaya street in Kyiv.

Princess Olga Street in Lviv.

In Vitebsk, in the city center at the Holy Spiritual Convent, there is the St. Olga Church.

In St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican, to the right of the altar in the northern (Russian) transept, there is a portrait image of Princess Olga.

St. Olginsky Cathedral in Kyiv.

Orders:

Insignia of the Holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Princess Olga - established by Emperor Nicholas II in 1915;

“Order of Princess Olga” - state award of Ukraine since 1997;

The Order of the Holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Princess Olga (ROC) is an award of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Olga's image in art

In fiction:

Antonov A.I. Princess Olga;

Boris Vasiliev. "Olga, Queen of the Rus";

Victor Gretskov. "Princess Olga - Bulgarian princess";

Mikhail Kazovsky. "The Empress's Daughter";

Alexey Karpov. “Princess Olga” (ZhZL series);

Svetlana Kaydash-Lakshina (novel). "Princess Olga";

Alekseev S. T. I know God!;

Nikolay Gumilyov. "Olga" (poem);

Simone Vilar. "Svetorada" (trilogy);

Simone Vilar. "The Witch" (4 books);

Elizaveta Dvoretskaya “Olga, the Forest Princess”;

Oleg Panus “Shields on the Gates”;

Oleg Panus “United by Power.”

In cinema:

“The Legend of Princess Olga” (1983; USSR) directed by Yuri Ilyenko, in the role of Olga Lyudmila Efimenko;

"The Saga of the Ancient Bulgars. The Legend of Olga the Saint" (2005; Russia) directed by Bulat Mansurov, in the role of Olga.;

"The Saga of the Ancient Bulgars. Vladimir's Ladder Red Sun", Russia, 2005. In the role of Olga, Elina Bystritskaya.

In cartoons:

Prince Vladimir (2006; Russia) directed by Yuri Kulakov, voiced by Olga.

Ballet:

“Olga”, music by Evgeniy Stankovych, 1981. It was performed at the Kiev Opera and Ballet Theater from 1981 to 1988, and in 2010 it was staged at the Dnepropetrovsk Academic Opera and Ballet Theater.

Princess Olga is one of the outstanding and mysterious personalities on the Kiev throne. She ruled Russia for 15 years: from 945 to 960. And she became famous as the first female ruler, as a firm, decisive politician and as a reformer. But some facts of her affairs and life are very contradictory, and many points have not yet been clarified. This makes it possible to question not only her political activities, but her very existence. Let's look at the data that has reached us.

We can find information about Olga’s life in the “State Book” (1560-1563), which gives a systematic presentation of Russian history, in the “Tale of Bygone Years”, in the collection “On the Ceremonies of the Byzantine Court” by Constantine Porphyrogenitus, in the Radziwill and some others chronicles. Some of the information that can be gleaned from them is controversial, and sometimes the exact opposite.

Personal life

The biggest doubts are raised about the dating of the princess's birth. Some chroniclers report the year 893, but then she would have gotten married at the age of ten and given birth to her first son at 49. Therefore, this date seems unlikely. Modern historians put forward their dating: from 920 to 927-928, but confirmation of these guesses is nowhere to be found.

Olga’s nationality also remained unclear. She is called a Slav from Pskov (or from ancient times near Pskov), a Varangian (due to the similarity of her name with the Old Scandinavian Helga), and even a Bulgarian. This version was put forward by Bulgarian historians, translating the ancient spelling of Pskov Pleskov as Pliska, the capital of what was then Bulgaria.

Olga's family is also controversial. It is generally accepted that she is of humble origin, but there is the Joachim Chronicle (although its authenticity is in doubt), which reports the princely origin of the princess. Some other chronicles, also controversial, confirm the speculation that Olga was allegedly the daughter of the Prophetic Oleg, the regent of Igor Rurikovich.

Olga's marriage is the next controversial fact. According to the Tale of Bygone Years, the wedding took place in 903. There is a beautiful legend that talks about the unintentional meeting of Igor and Olga in the forests near Pskov. Allegedly, the young prince was crossing the river on a ferry, which was driven by a beautiful girl in men's clothing - Olga. He proposed to her - she refused, but later their marriage still took place. Other chronicles report a legend about an intentional marriage: the regent Oleg himself chose a wife for Igor - a girl named Beautiful, to whom he gave his name.

We cannot know anything about Olga’s future life. Only the fact of the birth of her first son is known - approximately 942. She appears again in chronicles only after the death of her husband in 945. As you know, Igor Rurikovich died while collecting tribute in the Drevlyan lands. His son was then a three-year-old child, and Olga took control of the government.

Beginning of reign

Olga began with the massacre of the Drevlyans. Ancient chroniclers claim that the Drevlyan prince Mal twice sent matchmakers to her with an offer to marry him. But the princess responded with refusals, brutally killing the ambassadors. Then she made two military campaigns in the lands of Mal. During this time, more than 5,000 Drevlyans were killed and their capital, the city of Iskorosten, was destroyed. This begs the question: how after this Olga was canonized as a saint equal to the apostles and called Saint?

The subsequent reign of the princess was of a more humane nature - she set the first example of the construction of buildings made of stone (the Kiev palace and Olga's country residence), traveled around the lands of Novgorod and Pskov, and established the amount of tribute and the places where it was collected. But some scientists doubt the truth of these facts.

Baptism in Constantinople

All sources name only the approximate date, place and godchildren of Olga, which also raises many questions. But most of them agree that she accepted the Christian faith in 957 in Constantinople, and her godparents were the Byzantine Emperor Roman II and Patriarch Polyeuctus. Slavic chronicles even cite a legend about how the emperor wanted to take Olga as his wife, but she outwitted him twice and left him with nothing. But in the collection of Constantine Porphyrogenitus it is indicated that Olga was already baptized during the visit.

Assumptions

Of course, such contradictions in the sources can be explained by the remoteness of Olga’s era. But we can assume that the chronicles tell us about two (or even more) women of the same name. After all, at that time in Rus' there was a custom of polygamy, and there is information about several wives of Igor. Maybe in 903 the prince took one Olga of the same origin as his wife, and another Olga of a different origin gave birth to Svyatoslav. This easily explains the confusion with the year of her birth, the date of her marriage and the birth of her son.

And in the same way I would like to believe that a completely different Olga was canonized, not the one who carried out brutal reprisals against the Drevlyans.

They were also just waiting for an opportunity to plunder the Russian land. But Princess Olga, Svyatoslav’s mother, turned out to be a very intelligent woman, moreover, of a firm and decisive character; fortunately, among the boyars there were experienced military leaders devoted to her.

First of all, Princess Olga cruelly took revenge on the rebels for the death of her husband. This is what the legends say about this revenge. The Drevlyans, having killed Igor, decided to settle the matter with Olga: they chose twenty of their best husbands from among them and sent to her with an offer to marry their prince Mal. When they arrived in Kyiv and Princess Olga found out what was the matter, she told them:

“I love your speech, I can’t resurrect my husband.” I want to honor you tomorrow in front of my people. Go now to your boats; tomorrow I will send people for you, and you tell them: we don’t want to ride or walk, carry us in boats, and they will carry you.

When the next morning people came to the Drevlyans from Olga to call them, they answered as she had taught.

“We are in bondage, our prince was killed, and our princess wants to marry your prince!” - said the people of Kiev and carried the Drevlyans in a boat.

The ambassadors sat arrogantly, proud of their high honor. They brought them to the yard and threw them with the boat into a hole that had previously been dug on Olga’s orders. The princess leaned towards the pit and asked:

- Is honor good for you?

“This honor is worse for us than Igor’s death!” - answered the unfortunate ones.

Princess Olga's revenge on the Drevlyans. Engraving by F. Bruni

Princess Olga ordered to cover them alive with earth. Then she sent ambassadors to the Drevlyans to say: “If you really ask me, then send your best men for me, so that I come to you with great honor, otherwise the people of Kiev will not let me in.”

New ambassadors from the Drevlyans arrived. Olga, according to the custom of that time, ordered a bathhouse to be prepared for them. When they entered there, they were locked up by order of the princess and burned along with the bathhouse. Then she sent again to tell the Drevlyans: “I’m already on my way to you, prepare more honey - I want to create it on the grave of my husband.” funeral feast(wake)".

The Drevlyans fulfilled her demand. Princess Olga with a small retinue came to Igor’s grave, cried for her husband and ordered her people to build a high burial mound. Then they began to hold a funeral feast. The Drevlyans sat down to drink, the youths (younger warriors) Olgins served them.

-Where are our ambassadors? - the Drevlyans asked the princess.

“They are coming with my husband’s retinue,” Olga answered.

When the Drevlyans became drunk, the princess ordered her squad to cut them down with swords. Many of them were cut down. Olga hurried to Kyiv, began to gather a squad and the next year went to the Drevlyansky land; She also had her son with her. The Drevlyans thought about fighting in the field. When both armies came together, little Svyatoslav was the first to throw a spear, but his childish hand was still weak: the spear barely flew between the horse’s ears and fell at his feet.

- The prince has already begun! - the commanders shouted. - Squad, forward, follow the prince!

The Drevlyans were defeated, fled and took refuge in cities. Princess Olga wanted to take the main one, Korosten, by storm, but all efforts were in vain. The residents defended themselves desperately: they knew what awaited them if they surrendered. The Kyiv army stood near the city for a whole summer, but could not take it. Where strength does not take you, sometimes you can take it with intelligence and dexterity. Princess Olga sent to tell the Korosten people:

– Why don’t you give up? All the cities have already surrendered to me, are paying tribute and calmly cultivating their fields, and you, apparently, want to wait until you starve to death?!

The Korostenians replied that they were afraid of revenge, and they were ready to give tribute in both honey and furs. Princess Olga sent to tell them that she had already taken enough revenge and demanded only a small tribute from them: three doves and three sparrows from each yard. The besieged were glad that they could get rid of trouble so cheaply, and fulfilled her wish. Olga ordered her soldiers to tie pieces of tinder (that is, rags soaked in sulfur) to the birds’ feet and, when it got dark, light the tinder and release the birds. The sparrows flew under the roofs to their nests, the pigeons to their dovecotes. The houses at that time were all wooden, with thatched roofs. Soon Korosten was ablaze from all over, all the houses were engulfed in fire! In horror, the people rushed out of the city and fell straight into the hands of their enemies. Princess Olga took the elders captive, and ordered the common people to beat some, gave others into slavery to her warriors, and imposed a heavy tribute on the rest.

Olga sacrificed many captured Drevlyans to the gods and ordered them to be buried around Igor’s grave; then she held a funeral feast for her husband, and war games took place in honor of the late prince, as custom required.

If Olga was not so cunning, and the Drevlyans were as simple and trusting as legend says, then the people and the squad still believed that this was exactly what happened: they praised the princess for the fact that she cunningly and cruelly took revenge on the Drevlyans for their death husband In the old days, the morals of our ancestors were harsh: bloody revenge was required by custom, and the more terrible the avenger took revenge on the murderers for the death of his relative, the more praise he deserved.

Having pacified the Drevlyans, Princess Olga with her son and retinue went through their villages and cities and established what tribute they should pay her. The next year, she and her squad walked around her other possessions, divided the lands into plots, and determined what taxes and dues the residents had to pay her. The intelligent princess, apparently, clearly understood how much evil there was from the fact that the prince and his squad took tribute as much as they wanted, but the people did not know in advance how much they were obliged to pay.

Princess Olga in Constantinople

Olga’s most important deed was that she was the first of the princely family to convert to Christianity.

Princess Olga. Baptism. The first part of the trilogy "Holy Rus'" by S. Kirillov, 1993

Most sources consider the date of Princess Olga's baptism in Constantinople to be the fall of 957.

Upon returning to Kyiv, Olga strongly wanted to baptize her son Svyatoslav into the Christian faith.

“Now I have come to know the true God and I rejoice,” she said to her son, “be baptized, you too will know God, there will be joy in your soul.”

- How can I accept a different faith? – Svyatoslav objected. - The squad will laugh at me!..

“If you are baptized,” Olga insisted, “everyone will follow you.”

But Svyatoslav remained adamant. The soul of the warrior-prince was not ready for baptism, for Christianity with its meekness and mercy.

After the murder of Prince Igor, the Drevlyans decided that from now on their tribe was free and they did not have to pay tribute to Kievan Rus. Moreover, their prince Mal made an attempt to marry Olga. Thus, he wanted to seize the Kyiv throne and single-handedly rule Russia. For this purpose, an embassy was assembled and sent to the princess. The ambassadors brought rich gifts with them. Mal hoped for the cowardice of the “bride” and that she, having accepted expensive gifts, would agree to share the Kiev throne with him.

At this time, Grand Duchess Olga was raising her son Svyatoslav, who, after Igor’s death, could lay claim to the throne, but was still too young. Voivode Asmud took charge of young Svyatoslav. The princess herself took up state affairs. In the fight against the Drevlyans and other external enemies, she had to rely on her own cunning and prove to everyone that the country, which had previously been ruled only by the sword, could be ruled by a woman’s hand.

War of Princess Olga with the Drevlyans

When receiving the ambassadors, Grand Duchess Olga showed cunning. By her order, the boat on which the ambassadors sailed , They picked him up and carried him into the city along the abyss. At one point the boat was thrown into the abyss. The ambassadors were buried alive. Then the princess sent a message agreeing to the marriage. Prince Mal believed in the sincerity of the message, deciding that his ambassadors had achieved their goal. He gathered noble merchants and new ambassadors to Kyiv. According to ancient Russian custom, a bathhouse was prepared for the guests. When all the ambassadors were inside the bathhouse, all exits from it were closed, and the building itself was burned. After this, a new message was sent to Mal that the “bride” was going to him. The Drevlyans prepared a luxurious feast for the princess, which, at her request, was held not far from the grave of her husband, Igor. The princess demanded that as many Drevlyans as possible be present at the feast. The prince of the Drevlyans did not object, believing that this only increased the prestige of his fellow tribesmen. All guests were given plenty of drink. After this, Olga gave a signal to her wars and they killed everyone who was there. In total, about 5,000 Drevlyans were killed that day.

In 946 Grand Duchess Olga organizes a military campaign against the Drevlyans. The essence of this campaign was a demonstration of strength. If earlier they were punished by cunning, now the enemy had to feel the military power of Rus'. The young prince Svyatoslav was also taken on this campaign. After the first battles, the Drevlyans retreated to the cities, the siege of which lasted almost the entire summer. By the end of the summer, the defenders received a message from Olga that she had had enough of revenge and did not want it anymore. She asked only for three sparrows, as well as one dove for each resident of the city. The Drevlyans agreed. Having accepted the gift, the princess’s squad tied the already lit sulfur tinder to the birds’ paws. After this, all the birds were released. They returned to the city, and the city of Iskorosten was plunged into a huge fire. The townspeople were forced to flee the city and fell into the hands of the Russian warriors. Grand Duchess Olga condemned the elders to death, some to slavery. In general, Igor’s murderers were subject to an even heavier tribute.

Olga's adoption of Orthodoxy

Olga was a pagan, but often visited Christian cathedrals, noticing the solemnity of their rituals. This, as well as Olga’s extraordinary mind, which allowed her to believe in God Almighty, was the reason for baptism. In 955, Grand Duchess Olga went to the Byzantine Empire, in particular to the city of Constantinople, where the adoption of a new religion took place. The patriarch himself was her baptizer. But this did not serve as a reason for changing the faith in Kievan Rus. This event did not in any way alienate the Russians from paganism. Having accepted the Christian faith, the princess left government, devoting herself to serving God. She also began helping to build Christian churches. The baptism of the ruler did not yet mean the baptism of Rus', but it was the first step towards the adoption of a new faith.

The Grand Duchess died in 969 in Kyiv.

Regency under Svyatoslav: 945-962

From the biography

- Princess Olga is cunning (according to legend), holy (as the church called her), wise (as she remains in history).

- In the chronicle she is described as a beautiful, intelligent, energetic woman and, at the same time, a far-sighted, cold-blooded and rather cruel ruler

- There is a legend about how Olga brutally avenged the death of her husband, Igor. The first embassy was buried alive in the ground. The second was interrupted after a drunken feast. By order of Olga, the capital of the Drevlyans, Iskorosten, was burned (she asked from each yard for two doves and a sparrow, to whose paws a lit tow was tied). 5,000 people died.

- Such revenge was not considered cruelty in those days. It was a natural desire to take revenge for a loved one.

- Olga ruled during the childhood of her son Svyatoslav, but even after that she remained in leadership for a long time, since Svyatoslav spent most of his time on military campaigns.

- Princess Olga was one of the first rulers who paid great attention to diplomacy in relations with neighboring countries.

- In 1547 she was canonized.

Historical portrait of Olga

Areas of activity

1.Domestic policy

| Areas of activity | Results |

| Improving the taxation system. | Carried out tax reform, introduced lessons- the size of the tribute, which was clearly defined. |

| Improving the system of administrative division of Rus'. | Conducted administrative reform: introduced administrative units - camps and churchyards, where the tribute was taken. |

| Further subjugation of the tribes to the power of Kyiv. | She brutally suppressed the uprising of the Drevlyans, set fire to Iskorosten (she avenged the death of her husband according to custom). It was under her that the Drevlyans were finally subjugated. |

| Strengthening Rus', active construction. | During Olga’s reign, the first stone buildings began to be built, stone construction began. She continued to strengthen the capital, Kiev. During her reign, cities were actively improved, and the city of Pskov was founded. |

2. Foreign policy

| Areas of activity | Results |

| The desire to strengthen the country's prestige on the world stage through the adoption of Christianity. | In 955 g (957 g). accepted the Christian faith under the name Elena. But her son, Svyatoslav, did not support his mother. 959 - embassy to Germany to Otto I. The German bishop Adelbert was expelled by pagans from Kyiv in the same year. |

| Defense of Kyiv from raids. | 968 - led the defense of Kyiv from the Pechenegs. |

| Strengthening ties with the West and Byzantium | She pursued a skillful diplomatic policy with neighboring countries, especially Germany. Embassies were exchanged with her. |

RESULTS OF ACTIVITY

- Strengthening princely power

- Strengthening and flourishing of the state, its power

- The beginning of stone construction in Rus' was laid.

- Attempts have been made to adopt a single religion - Christianity

- Significant strengthening of the international authority of Rus'

- Expansion of diplomatic ties with the West and Byzantium.

Chronology of Olga's life and work

Princess Olga.

Nesterov, 1892

Saint Olga.

Icon

Monument to Princess Olga, Apostle Andrew, Cyril and Methodius in Kyiv, on Mikhailovskaya Square

1911 Authors: I. Kavaleridze, P. Snitkin, architect V. Rykov.

Olga's baptism in Constantinople.

N. Akimov.

Basic terms and conditions of the life insurance contract

Currency option. Options

Why do you dream about a baby boy or girl?

Interesting facts and events from around the world

Shocking facts about everything