Turgenev wrote his story “Mumu” in 1852, but it was published after 2 long years of struggle against censorship in one of the issues of the Sovremennik magazine.

To write such a powerfully impressive work, you yourself need to experience something touching in life, and the author experienced this in childhood and youth. He grew up in a family where the mother was a domineering woman, often offended children, beat them with rods, and treated serfs with hatred.

The story is written in the style of classical realism, because it is based on the author’s personal memories and experiences, and the characters are prototypes of people whom he knew well.

The difficult, hopeless life of serfs in Russia is the main theme of the story. But the author also raises themes of love, fidelity, inner freedom, human relationships.

In the image of the main character we see a collective image of all serfs. They could be sold, exchanged, or lost at cards. But despite all this, they remained hardworking, kind, resilient people, they knew how to sympathize and empathize. The only thing they could not do was fight their situation in order to gain freedom. The title of the work suggests that the serfs silently endured all the hardships of their lives; they, like Gerasim, were silent.

The author endowed the main character of the work with positive traits. The janitor Gerasim works conscientiously, he is respected by those around him, he sincerely loves the laundress Tatyana. But, having learned that the lady is forcibly giving her in marriage to another person, she is very worried and with all her heart becomes attached to the dog Mumu, whom he saved, with whom she shares all her hardships and hardships. And when the dog became an enemy for the lady, Gerasim is forced to drown her. This scene is very touchingly described.

Gerasim lost everything in his life, but at the same time remained a man who did not lose his dignity, who did not become bitter against the world. An internal protest to the life he lived is gradually brewing in him, and with the loss of his last beloved being, this protest intensifies. Gerasim has nothing left to lose. With this mental shock, Gerasim gains inner freedom, he gets rid of his slavish habits of obeying his mistress and leaves her for his native village. He gained freedom, but also doomed himself to loneliness and lived out his life on his own.

Turgenev was very worried about the future of Russia, he was an opponent of serfdom, and with this story he showed that the future of the serfs was in their struggle for their independence and freedom.

Analysis 2

The story “Mumu” by Ivan Sergeevich Turgenev was written in 1852. It tells about the life of Gerasim, a mute janitor, whose life found meaning after he adopted a little mongrel. Since he was mute and could not speak clearly, he addressed her with a small moo, similar to the moo of a moo-moo cow. This is where the title of this story comes from.

Gerasim looked after and watched the dog until it burst into the kitchen and scared the lady. In turn, the lady became angry and ordered the animal to be drowned. Gerasim personally drowns Mumu with his own hands and, unable to bear the burden of his experiences, goes to his native village, where he remains for the rest of his life.

The prototype of the story was an incident the author saw on his own estate. His mother, Varvara Petrovna, was a very complex, domineering and headstrong woman. She became the prototype of that cruel lady described by the writer in the story. Andrey also lived in reality and was mute from birth, but the author changed his name to Gerasim. Only Andrei did not leave the landowner, but continued to dutifully serve further.

The character of the main characters is described very revealingly. The old lady had a very bad character. In terms of appearance, the author does not give anything other than “with a sweet smile on wrinkled lips.” Thanks to this, the author tries to draw the reader’s attention to the situation and characters itself, rather than to material and external qualities. The main character had nervous attacks, during which she became hot and nervous more than necessary. During such a fit, she marries a drunkard shoemaker with the washerwoman Tatyana, without asking the girl.

This character collects all the negative traits of lordly personalities. Their careless attitude towards the serf's soul as a thing that they can drink away, lose, give away and sell.

Gerasim's character is very calm, flexible and hard-working. The author describes him as a big, strong man. His only drawback is muteness. Gerasim postpones the wedding of his beloved Tatyana with a drunkard. Finds a reflection of his love in the dog Mumu. After the lady orders, he personally drowns the dog, the only thing that he loves and who loves him in return with all his shortcomings.

This character is a reflection of the entire serf-owning layer. He is flexible, silent and hard-working. He never says anything against the will of the landowners and fulfills all their whims.

The author shows the reader how difficult the life of serfs can sometimes be. Despite the same human experiences as all other people, the landowners do not see anything humane in them because of their self-will and pride. Also, the writer gives a small warning for the boyars during the scene after Gerasim drowned Mumu and came to the lady. The lady was very frightened by Gerasim's gaze, filled with pain and suffering brought to him. Perhaps this suggests that sooner or later, if you do not change your attitude towards the serfs, their anger and rage will result in an open struggle for freedom.

Several interesting essays

- Essay Is it difficult to be a parent? (final December)

Each task can be done in a different way. Of course, undoubtedly, if we are talking about some objective criteria, then in order to walk two miles, you need to walk two miles, and even then, it is possible to walk in completely different ways.

- Review of the story About Chekhov's Love

This story raises many questions about love. Why don't people choose suitable partners for themselves? Or why do they choose people who are suitable, but with whom they cannot build relationships for some external reason?

- Analysis of Natalie Bunin's story

The novel “Natalie” is included in “Dark Alleys” - a collection of stories and miniatures by Ivan Bunin, the main theme of which is great love - mutual and unhappy, passion and relationships between a man and a woman.

- Essay Female images in the novel Evgeny Onegin Pushkin

The romantic work “Eugene Onegin” contains a galaxy of female images. The author poetically sings of the best qualities of Russian women.

- The image of Parasha in the poem The Bronze Horseman by Pushkin essay

The work “The Bronze Horseman” tells the story of an ordinary poor official who lived in the newly built city of St. Petersburg.

Everyone knows that the plot of “Mumu” has a real source: this story took place on Lutovinov’s estate; the heroes, Gerasim and Kapiton, were not invented. The lady was immediately recognizable as Varvara Petrovna Lutovinova, who so subtly knew how to torment her serfs. However, the meaning of what is told in “Mumu” significantly exceeds both the content of the plot of the work and Lutovinov’s story itself about the janitor Andrei and his dog.

Turgenev's story was immediately perceived as anti-serfdom. Critics wrote that although its plot is “insignificant,” it makes a strong, stunning impression.

At the same time, some researchers believe that the story contains a broader problem area than the sphere of purely social conflict of the era of serfdom. In particular, S. Brover connects the image of Gerasim with characters from Christian mythology and Russian folklore. By the way, note that Iv. Aksakov, reflecting on Gerasim, wrote that in Turgenev’s character “one can hear... the presence of another, deep thought that lies beyond the scope of the work and is not exhausted by the work.”

How does Gerasim first appear before the reader? He is strong and tall. An inch is 4.45 centimeters. But when in Russian folk speech they talk about height in vershoks, they add them to 2 arshins (arshin - 71.1 cm). Consequently, Gerasim’s height turns out to be 1.95 m, which, of course, is surprising, but still really possible.

Turgenev’s use of popular speech in calculating the hero’s height is quite organic. His Gerasim is a peasant, a plowman. It is appropriate to talk about it in popular language. The author’s depiction of the plowman hero as a two-meter-tall giant is also appropriate. The Slavic tradition is characterized by the exaltation of peasant labor, and with it the image of the farmer.

Previously, his huge palms “leaned” on the plow, his strong hands held a scythe, which he wielded crushingly, and a three-yard flail. Now he has a broom and a shovel in his hands, a symbol of the boring prose of urban civilization (S. Brover).

For Gerasim, who picked up a broom and shovel, boredom really becomes an unrelenting companion, since Gerasim’s classes in his new position seemed to him a joke after the hard peasant work; in half an hour everything was ready.

The new position is also boring for him because everything associated with it is imposed labor, made a duty. While hard peasant work, organic to someone born for the land (that’s why Gerasim the Plowman was given heroic strength), gives him true joy.

It was eternal (“tireless”) joyful work in the open air, on a vast land. Nothing hampered the plowman’s movements (no sheepskin coats or caftans!) and he, like a hero, “cut up” with a plow huge chunks of earth that smelled like forbs, mowed with a sweeping sweep, and “non-stop” threshed.

In the city, Gerasim is doomed to monotonous activities that do not correspond to his ideas about work (hence the boredom!): keeping the yard clean,” “bringing a barrel of water twice a day,” “carrying and chopping wood for the kitchen and home,” “Don’t let strangers in and keep watch at night.”

It should be emphasized that in the enclosed space of the hero’s city life, an exceptional pattern of movements (there and back) prevails, while the natural cycle (spring-summer-autumn) does not make peasant life monotonous. This especially confirms the spirituality of Gerasim’s activities.

The lady is a capricious, selfish creature. But at the same time, she is unusually pitiful, if only because she cannot influence much of what is happening in her house, for example, reason with the drunkard Capiton. Gavrila and the housekeeper rob her mercilessly; the lady’s servants are deceitful and lazy. And its power is manifested exclusively in whims and pitiful quirks, but which nevertheless distort the destinies of people.

Endowed with power, a pitiful creature is capable of imposing its own will on others: dooming a girl to a hopeless life with a drunkard, turning a giant, a hero into a janitor, and servants into a crowd of slaves (you can steal from the owner, but still remain his slave)...

Someone else's will not only makes a person powerless. Being a principle unnatural to human nature, it is capable of deforming the qualities of his soul.

The closeness and isolation of Gerasimov’s new life brings him, always alienated by his misfortune from the community of people, face to face with those who are called servants in the manor’s house.

And yet why is Gerasim the most remarkable person in the lady’s courtyard environment? To answer this question, it is necessary to draw up a “collective portrait” of the old lady’s servants.

Everyone who was familiar with V.P. Lutovinova and her estate in Spassky could confirm the documentary basis of the picture of courtyard life in the story “Mumu”. Like the writer’s mother (there were up to several dozen families of housekeepers in Spassky), the old lady kept a “numerous” servant: laundresses, seamstresses, carpenters, tailors and seamstresses, a saddler, maids, a shoemaker, the lady’s house doctor, “who constantly brought the lady cherry laurel drops” ( These drops were also used by the family doctor Varvara Petrovna).

As for the atmosphere in the old lady’s house, here, as in Spassky, everything was trembling, moving, fussing, disingenuous, catching signs of approval or anger. And, really, there was a reason. Like Varvara Petrovna, the old lady loved to test her servants for devotion and obedience, while performing a whole theatrical performance: Gerasim is a hard worker; it is labor that constitutes the content of his life both in the village and in the city. The servants are depicted by Turgenev as idle. In the story, the house servants are never shown working; they drink, sleep, gossip, hang around the yard, keep an eye on Gerasim and that’s all. In this regard, the image of the yard Broshka, with no specific occupation at all, is clear. The lady considered him a gardener. However, the remark of the butler Gavrila is noteworthy when he instructs Broshka to guard the entrance to Gerasim’s closet: “...What should you do? Take a stick and sit here...” - confirming the absolute inaction of this servant at the lady’s court. The only exception to the rule of being idle, established by the servants, is Tatyana, who worked for two. It would not be superfluous to emphasize that in this too she is a kindred spirit to Gerasim (in the village he worked for four and in the city he diligently fulfilled... his duty).

It is also significant that even the craftsmen from among the master’s household are either drunkards (like the shoemaker Kapiton Klimov) or do not know how to do their job, like, for example, the house doctor Khariton.

But, of course, the drunken shoemaker Kapiton, who considered himself a creature “offended and not appreciated,” especially stood out from among the courtyards. How much swagger and arrogance this man carries within himself! Just look at his shaking of his shoulders and complaints about life in Moscow - in some kind of outback! At the same time, we see before us, as the butler Gavrila says, “a bullied man!”, riotous, carefree, in a shabby and tattered frock coat, in “patched trousers,” and, most impressively, in holey boots. Truly a shoemaker without boots, by the way, desperately complaining that he lives without anything to do.

But what the servants have an impeccable command of is the ability to keep in tune with the mood of the hostess. The behavior of the hanger-on, who is at a loss as to the lady’s reaction to Mumu, whom she saw for the first time, is indicative. But the apogee of the servants' servility comes in the events that unfolded around Mumu and her master.

The scene in which it is shown with what fantastic speed the zealous servants pass along the chain the news of the night barking of Gerasim’s dog and, accordingly, the mistress’s suffering, is absolutely stunning. In the picture of the decisive onslaught on the Gerasimovo refuge, Turgenev depicts such a surge of servile zeal that much of the behavior of the servants is difficult to rationally comprehend.

There are several scenes in the work that cause outright bewilderment and even laughter. For example, if it is possible to explain why a whole crowd of people (footmen and cooks led by the butler Gavrila) is advancing on Gerasim’s closet, then it is completely incomprehensible why the butler held his cap during this throw, although there was no wind? One can only imagine the attack on the Gerasimov Shelter so rapid that its participants even tore off their hats as they ran.

Or why, standing under the door of Gerasim’s closet, Gavrila shouted: “Open it... They say open it!”? Perhaps, from excessive zeal, he even forgot about the deafness of the janitor. It is also unclear why, when the door of the closet quickly swung open and all the servants immediately rolled head over heels down the stairs, Gavrila, who, as we know, was standing right next to Gerasim’s door, found himself first on the ground?

In general, from the outside, this whole decisive attack on Gerasim’s closet resembles the attack of hordes of Lilliputians on the sleeping Gulliver. But if Swift’s hero, accepting the laws of the land of Lilliputians and its inhabitants, internally becomes like them, in fact, becomes the same Lilliputian, then Turgenev’s Gerasim was and remains the Man-Mountain. Having forcefully opened the doors of his closet and thereby forcing the servants to slide down the stairs, he, the giant, continued to stand at the top and looked with a grin at the fuss of these little people.

A giant and little people - this is the result of Turgenev’s thoughts about the hero-plowman and the strangers among whom he found himself by the will of the master.

It should be especially emphasized that if for the author Gerasim is a hero, a mighty man, then among the lady’s entourage he is associated with the unclean (“God forgive this devil”, “a devil of this kind”, “forest kikimora”)..

In the world of little people, Gerasim falls into the category of outcasts, outcasts. Following the morality formed by society, “little people” at all times refused to accept people different from them. They constantly spy on the "giants". So in Mumu the servants are watching Gerasim (“From all corners, from under the curtains outside the windows they looked at him”; “Soon the whole house learned about the tricks of the dumb janitor”; “Antipka spied on Gerasim through a crack”).

But the most important thing is not even this, but the indifference of the majority of the servants to Gerasim’s suffering. When he tries to find the Mumu stolen by Stepan, those who knew only laughed at him in response...! All this is so reminiscent of a scene from Pushkin’s fairy tale about the seven heroes, in which Prince Elisha goes to the people in search of his bride. “But who laughs in his face, who would rather turn away...” And then Elisha turns to the forces of nature - the wind, the moon, the sun...

And isn’t the story of Ivan Ivanovich (G. Troepolsky. “White Bim, Black Ear”), whose loneliness was also shared by a dog, not people, similar to the friendship between a lonely man and a dog described by Turgenev? But Turgenev shows the hero’s attempts to become part of the world into which he was forcibly plunged. For this, the writer needed Tatiana's story in the story "Mumu".

This article is devoted to the work of I.S. Turgenev. It will carefully analyze the motives of behavior of the main character of the story “Mumu” - the janitor Gerasim. Probably, those who read, but did not have sufficient psychological insight, were tormented since school by the question of why Gerasim drowned Mumu. During the “investigation” the answer will be given.

Personality of Gerasim

The mighty mute Gerasim was uprooted from his native hut in the village and transplanted into the alien urban soil of Moscow. He was two meters tall. He had an abundance of natural power. A Moscow lady took an eye on him and ordered him to be transported from the village to her house. She identified him as a janitor, for he was a noble worker.

No matter how far this information may seem to the reader from answering the question of why Gerasim drowned Mumu, it is very important and is directly related to him. This is the foundation for understanding the hero’s inner world.

Love triangle: Gerasim, Tatiana and Kapiton

The lady had one simple girl in her employ - Tatyana (she worked as a laundress). Gerasim liked the young woman, although both the other servants and the mistress herself understood that such a marriage was hardly possible for obvious reasons. Nevertheless, Gerasim tenderly cherished within himself a timid hope, firstly, for reciprocity, and secondly, that the lady would consent to the marriage.

But, unfortunately, the hopes of the main character were not destined to come true. The quarrelsome and self-centered lady decided in her own way: the drunken shoemaker, who had gotten out of hand, was appointed Tatyana’s husband by the lord’s permission. He himself is not against it, but he was afraid of Gerasim’s reaction to this news. Then the master's servants resorted to a trick: knowing that the dumb janitor could not stand drunkards, the servants forced Tatyana to walk in front of Gerasim drunk. The trick was a success - the janitor himself pushed his sweetheart into Kapiton’s arms. True, the lady’s experiment did not end well. Her shoemaker drank himself to death even in the hands of a hardworking and, one might say, gentle to the point of slavery washerwoman. The unhappy couple's days passed joylessly in a remote village.

The love triangle is important in the context of answering the question of why Gerasim drowned Mumu, since it reveals the “chemistry” of the janitor’s future attachment to his dog.

Gerasim and Mumu

When Gerasim suffered from unspent love, he found a dog. She was only three weeks old. The janitor rescued the dog from the water, brought him to his closet, organized a rookery for the dog (it turns out it was a girl), and fed it milk.

In other words, now the love of a simple Russian mute man, unclaimed by a woman, is completely invested in the creature who unexpectedly appeared in his life. He names the dog Mumu.

The ending of the story

The main character's problems arose when the lady, who had not seen the dog before, suddenly discovered it. Mumu has lived with Gerasim like Christ in his bosom for more than a year. The owner was delighted with the dog. She asked to be immediately brought to the master's chambers. When the dog was delivered, she behaved warily and aggressively in an unfamiliar environment. She didn’t drink the owner’s milk, but began barking at the lady.

Of course, the lady could not bear such an attitude and ordered the dog to be removed from her possession. And so they did. Gerasim looked and looked for her, but never found her. But Mumu returned to her owner one fine day with a chewed leash around her neck. Gerasim realized that the dog did not run away from him on its own, and began to hide it from prying eyes in his closet, and he only took it out into the street at night. But on one such walking night, a drunk lay down near the fence of the owner’s estate. Mumu did not like drunkards, just like her owner, and began to bark hysterically and shrilly at the drunkard. She woke up the whole house, including the lady.

As a result, the dog was ordered to be disposed of. The servants took this too literally and decided to take Mumu’s life. Gerasim volunteered to relocate his beloved pet to a better world with his own hands. Then, unable to withstand the mental anguish, the janitor returned (in fact, fled) to his native land - to the village, again becoming an ordinary man. At first they looked for him, and when they found him, the lady said that “she doesn’t need such an ungrateful worker for nothing.”

Thus, if someone (most likely a schoolboy) decides to write an essay “Why Gerasim drowned Mumu,” he should answer this question in the context of the entire story, so that the author’s narrative acquires depth and richness.

Moral of the story

Turgenev specifically paints Gerasim so powerful in order to show in contrast his spiritual indecisiveness and timidity, one might say, slavery. The janitor drowned his dog not because he felt sorry for her: he imagined how she would wander around other people’s yards without him in search of food. He killed her because he could not resist the master's order and the pressure of other servants. And when the reader understands the whole essence of Gerasim’s inner world, he is shocked by two things: the skill of the writer and the deep tragedy of the story. After all, no one stopped Gerasim from escaping with the dog, in general, so to speak, from preparing the escape in advance when he realized that things were bad. But he didn’t do this, and all because of servile psychology.

Thus, to the question of why Gerasim drowned Mumu, the answers do not imply diversity. The key to understanding the work of I.S. Turgenev - in the slave psychology of Russian people, which the classic masterfully embodied in the image of a dumb janitor.

Mumu Tale

The story was written in the spring of 1851, in unusual conditions, “under arrest, on a congress” in St. Petersburg (see the preamble to “Notes of a Hunter,” p. 577). It was possible to publish “Mumu” only in the March issue of Sovremennik for 1854. The publication of the story caused extreme displeasure by the highest censorship authorities, and a remark was made to the Sovremennik censor V.N. Beketov, who allowed the clearly anti-serfdom work to be published. In 1856, when Turgenev was preparing a three-volume edition of his stories (undertaken on the initiative of P.V. Annenkov), in order to include “Muma”, it was necessary to seek special permission from the Minister of Education A.S. Norov. The Main Directorate of Censorship was forced to allow the re-publication of the story for political reasons, taking into account the psychology of the reader: banning a previously published story “could have more attracted the attention of the reading public to it (our italics - V. ( This material will help you write competently on the topic of Mumu Tale. A summary does not make it possible to understand the full meaning of the work, so this material will be useful for a deep understanding of the work of writers and poets, as well as their novels, stories, short stories, plays, and poems.) F.) and arouse inappropriate rumors, while its appearance in the collected works will no longer make on readers the impression that could be feared from the dissemination of this story in a magazine, with the lure of novelty" (Turgenev. Works, vol. V, p. .™-600). This submission by the Main Directorate of Censorship was authorized by the Minister of Education on May 31/June 12, 1856 (ibid.).

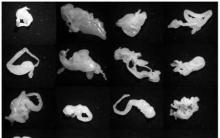

“Mumu” is a memoir story, the plot of which is taken from life. Almost all the prototypes of her characters are Turgenev's serf mothers, Varvara Petrovna Lutovinova. The writer’s half-sister, V.N. Shitova, whose childhood and youth were spent in Spassky, recalls: “Ivan Sergeevich’s entire story about these two unfortunate creatures is fiction. This whole sad drama happened before my eyes...” The prototype of Gerasim was Varvara Petrovna’s deaf-mute janitor, a man of rare beauty and strength.

“Varvara Petrovna showed off her giant janitor...

In Moscow, a shiny green barrel and a beautiful dapple-gray factory horse, with which Andrei went for water, were very popular at the fountain near the Alexander Garden, the memoirist recalls... His strength was extraordinary, and his hands were so large that when he Whenever someone picked me up, I felt like I was in exactly the right carriage. And this is how I was once brought into his closet, where I saw Mumu for the first time. A tiny dog, white with brown spots, was lying on Andrei’s bed...” (“Turgenev in the memoirs of his contemporaries”, vol. 1. M., “Fiction”, 1969, pp. 60-61). Zhitova’s memoirs, in addition to their authenticity, are also important for another reason. They provide an opportunity to evaluate the ideological sharpness of Turgenev’s plan. “Everyone knows the sad fate of Mumu,” writes Zhitova, “with the only difference being that Andrei’s affection for his mistress remains the same...” This difference is the essence of the story. After the death of Mumu, Gerasim leaves the city estate forever. “He hurried without looking back... to his village, to his homeland... He walked... with some kind of indestructible courage (our italics - V.F.), with desperate and at the same time joyful determination...” Turgenev ended the story with such an open ending, based on the highest idea of humanism and human dignity.

Modern criticism immediately drew attention to Turgenev’s story, comparing it with the most outstanding stories from “Notes of a Hunter” (“Notes of the Fatherland”, 1854, No. 4, pp. 90-91).

From completely different positions, but equally highly appreciated, the story was appreciated both in the Slavophile camp of the Aksakovs and in Westernizing and democratic circles, in particular by L. I. Herzen. He called Gerasim the Russian “Uncle Tom,” as if predicting the further European popularity of Turgenev’s short story, which during the writer’s lifetime became on a par with the famous Beecher Stowe novel (A. I. Herzen. Collected works in 30 volumes, vol. XIII . M., Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, p. 177),

"Mumu" left a deep mark in the history of Russian literature. Chekhov's “Kashtanka” and one of the most tragic and significant stories of the mature Chekhov “Tosca” go back to this Turgenev story created by the disgraced writer.

In the story: “Mumu,” not included in “Notes of a Hunter,” but close in spirit to the stories in this collection. In this story, two main characters are vividly outlined - the old lady and the deaf-mute janitor Gerasim. In addition to them, several other faces were depicted, also typical, although less striking.

Mumu. Cartoon

The old lady is depicted as a heartless tyrant, from whom even her own children turned their backs, and who lived out her last days, embittered, capricious, surrounded by a pack of hangers-on and a crowd of servants. Lies and stupid hatred, covered with servility and servility, reign in this house. Everything here trembles for fear of not pleasing the grumpy old woman; people don’t even dare to sleep at night when the lady can’t sleep.

The deaf and dumb Gerasim was brought to this lady's house from her village to serve as a janitor. This healthy, sedate and serious man was created for rural work and in the village he worked with pleasure and joy. The lady's whim tore him out of the expanse of fields and forests, and he found himself in a stuffy city. He languished here and was bored, but he did his job conscientiously and honestly. The servants feared and respected him. He fell in love with the washerwoman Tatyana, but the lady decided to marry her to the drunkard Kapiton, “for his correction.”

Gerasim's heart was broken, but he resigned himself to his fate. He found solace in the dog Mumu, which he raised and fed himself. But the dog annoyed the old lady by not only not coming up when she called her, but even baring her teeth and growling. Gerasim had to drown his only friend himself. After this second loss, Gerasim abandoned his mistress’s town house without permission and went to the village.

The heroine of the story is the washerwoman Tanya, a quiet, unresponsive girl who, under the humiliating oppression of serfdom, has been reduced to the point that she no longer has her own will. When she is told that the lady is marrying her to the drunkard Capiton, she submits to the decision meekly, without attempting to argue or resist...

This touching story is told simply and artlessly, but it has an even stronger effect on the reader. The useful and honest worker Gerasim, with his heroic strength, turns out to be helpless before the whim of an old, useless, hated old woman who has lost her mind. Offended by God, this hero must meekly endure human grievances. This helplessness of the serfs and the irresponsibility of the masters is the main tragedy of serfdom. And, of course, it was impossible to emphasize more strongly the ugliness of this system of life than to portray in the role of offended serfs - unhappy people, like Vlas’s family (“

Why do you dream about a baby boy or girl?

Interesting facts and events from around the world

Shocking facts about everything

What is the name of the modern state formerly called Persia?

It is a balm for the soul to see the spark of God in a person