We already live in the 21st century and we think that many secrets of science and technology have already been revealed, many social issues have been resolved, etc. Despite all these achievements, there are still places where, to this day, social society are divided into different layers - castes. What is the caste system? Caste (from the Portuguese casta - gens, generation and descent) or Varna (translated from Sanskrit - color), a term applied primarily to the main division of Hindu society in the Indian subcontinent. According to Hindu belief, there are four main Varnas (castes) - Brahmans (officials), Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (merchants) and Shudras (peasants, workers, servants). Of the most early works It is known from Sanskrit literature that the peoples who spoke Aryan dialects during the period of the initial settlement of India (from approximately 1500 to 1200 BC) were already divided into four main classes, later called Varnas. Modern castes are divided into a large number of sub-castes - jati. Hindus believe in reincarnation and believe that whoever follows the rules of his caste future life rises by birth to a higher caste, the one who violates these rules will lose social status. Brahmans Brahmans are the highest layer of this system. Brahmins serve as spiritual mentors, work as accountants and accountants, officials, teachers, and take possession of lands. They are not supposed to follow the plow or perform certain types of manual labor; women from their midst can serve in the house, and landowners can cultivate plots, but not plow. Members of each Brahmin caste marry only within their own circle, although it is possible to marry a bride from a family belonging to a similar subcaste from a neighboring area. When choosing food, a Brahmin observes many prohibitions. He has no right to eat food prepared outside his caste, but members of all other castes can eat food from the hands of brahmanas. Some Brahmin sub-castes may consume meat. Kshatriyas Kshatriyas are right behind the brahmanas in ritual terms and their task is mainly to fight and protect their homeland. Today, kshatriyas' occupations include working as estate managers and serving in various administrative positions and in the military. Most kshatriyas eat meat and, although they allow marriage with a girl from a lower subcaste, a woman under no circumstances can marry a man from a subcaste lower than her own. Vaishyas Vaishyas are the layers that engage in trade. Vaishyas are more strict in their observance of food regulations and are even more careful to avoid ritual pollution. The traditional occupation of Vaishyas is trade and banking; they tend to stay away from physical labor, but sometimes they are included in the management of the farms of landowners and village entrepreneurs, without directly participating in the cultivation of the land. Shudras “Pure” Shudras are a peasant caste. They, due to their numbers and ownership of a significant part of local land, play an important role in solving social and political issues in some areas. Shudras eat meat, and widows and divorced women are allowed to marry. The lower Shudras are numerous sub-castes whose profession is of a highly specialized nature. These are the castes of potters, blacksmiths, carpenters, joiners, weavers, oil makers, distillers, masons, barbers, musicians, tanners, butchers, scavengers and many others. Untouchables Untouchables are engaged in the dirtiest jobs and are in many ways outside the boundaries of Hindu society. They are engaged in cleaning dead animals from streets and fields, toilets, tanning leather, etc. n. Members of these castes are forbidden to visit the houses of the “pure” castes and take water from their wells, they are even forbidden to step on the shadows of other castes. Most Hindu temples until recently were closed to untouchables; there was even a ban on approaching people from higher castes closer than a set number of steps. The nature of caste barriers is such that they are believed to continue to pollute members of “pure” castes, even if they have long since abandoned their caste occupation and are engaged in ritually neutral activities such as agriculture. Although in others social conditions and situations, for example, being in an industrial city or on a train, an untouchable may have physical contact with members of higher castes and not to pollute them, in his native village untouchability is inseparable from him, no matter what he does. Throughout Indian history, the caste structure has shown remarkable stability in the face of change. Neither Buddhism, nor the Muslim invasion that ended with the formation of the Mughal Empire, nor the establishment of British rule shook fundamentals caste organization of society.

It will come across, I know many Indian travelers who live there for months, but are not interested in castes because they are not necessary for life.

The caste system today, like a century ago, is not exotic, it is part of the complex organization of Indian society, a multifaceted phenomenon that has been studied by Indologists and ethnographers for centuries, dozens of thick books have been written about it, so I will publish only 10 here interesting facts about Indian castes - about the most popular questions and misconceptions.

1. What is an Indian caste?

Indian caste is such a complex phenomenon that it is simply impossible to give an exhaustively complete definition!

Castes can only be described through a number of characteristics, but there will still be exceptions.

Caste in India is a system of social stratification, a separate social group related by origin and legal status its members. Castes in India are built according to the following principles: 1) general (this rule is always observed); 2) one profession, usually hereditary; 3) members of castes enter into relationships only among themselves, as a rule; 4) members of the caste as a rule do not eat with outsiders, with the exception of other Hindu castes of significantly higher social position than their own; 5) caste members can be determined by who they can accept water and food, processed and raw.

2. There are 4 castes in India

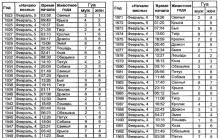

Now in India there are not 4, but about 3 thousand castes, they can be called differently in different parts of the country, and people with the same profession can have different castes in different states. For a complete list of modern castes by state, see http://socialjustice...

What nameless people on tourist and other near-Indian sites call 4 castes are not castes at all, they are 4 varnas - chaturvarnya - an ancient social system.

4 Varnas (वर्ना) is an ancient Indian class system. Brahmins (more correctly a brahmin) historically are clergy, doctors, teachers. Varna Kshatriyas (in ancient times it was called Rajanya) are rulers and warriors. Varna vaishyas are farmers and traders, and varna sudras are laborers and landless peasants who work for others.

4 Varnas (वर्ना) is an ancient Indian class system. Brahmins (more correctly a brahmin) historically are clergy, doctors, teachers. Varna Kshatriyas (in ancient times it was called Rajanya) are rulers and warriors. Varna vaishyas are farmers and traders, and varna sudras are laborers and landless peasants who work for others.

Varna is a color (in Sanskrit again), and each Indian varna has its own color: the Brahmins have white, the Kshatriyas have red, the Vaishyas have yellow, the Shudras have black, and before, when all representatives of the varnas wore a sacred thread - he was just their varna.

Varnas correlate with castes, but in very different ways, sometimes there is no direct connection, and since we have already delved into science, it must be said that Indian castes, unlike varnas, are called jati - जाति.

Read more about Indian castes at modern India

3. Caste Untouchables

The untouchables are not a caste. During times ancient india everyone who was not part of the 4 varnas automatically found themselves “outside” of Indian society; these strangers were avoided and not allowed to live in villages, which is why they are called untouchables. Subsequently, these untouchable strangers began to be used in the dirtiest, lowest-paid and shameful work, and formed their own social and professional groups, that is, untouchable castes, in modern India there are several of them, as a rule this is associated with either dirty work or murder living creatures or death, so that all hunters and fishermen, as well as gravediggers and tanners, are untouchable.

4. When did Indian castes appear?

Normatively, that is, legislatively, the caste-jati system in India was recorded in the Laws of Manu, which date back to the 2nd century BC.

The Varna system is much older; there is no exact dating. I wrote in more detail about the history of the issue in the article Castes of India, from varnas to modern times

5. Castes have been abolished in India

Castes in modern India are not abolished or prohibited, as is often written.

On the contrary, all castes in India are counted and listed in the annex to the Indian Constitution, which is called the Table of Castes. In addition, after the population census, changes are made to this table, usually additions; the point is not that new castes appear, but that they are recorded in accordance with the data indicated about themselves by the census participants.

Only discrimination on the basis of caste is prohibited, this is written in Article 15 of the Indian Constitution, see the test at http://lawmin.nic.in...

6. Every Indian has a caste

No, this is also not true.

Indian society is very heterogeneous in its structure, and besides the division into castes there are several others.

There are caste and non-caste, for example, representatives of Indian tribes (aboriginals, adivasis), with rare exceptions, do not have castes. And the part of non-caste Indians is quite large, see the census results http://censusindia.g...

In addition, for some misdemeanors (crimes) a person can be expelled from the caste and thus deprived of his status and position in society.

7. Castes exist only in India

No, this is a fallacy. There are castes in other countries, for example, in Nepal and Sri Lanka, since these countries developed in the bosom of the same huge Indian civilization, as well as on. But there are castes in other cultures, for example, in Tibet, and Tibetan castes do not correlate with Indian castes at all, since the class structure of Tibetan society was formed from India.

For the castes of Nepal, see Ethnic mosaic of Nepal

8. Only Hindus have castes

No, this is not the case now, we need to go deeper into history.

Historically, when the overwhelming majority of the Indian population professed - all Hindus belonged to some caste, the only exceptions were pariahs expelled from castes and the indigenous, tribal peoples of India who did not profess Hinduism and were not part of Indian society. Then other religions began to spread in India - India was invaded by other peoples, and representatives of other religions and peoples began to adopt from the Hindus their class system of varnas and the system of professional castes - jati. Now there are castes in Jainism, Sikhism, Buddhism and Christianity, but they are different from the Hindu castes.

It is curious that in northern India, in the modern states, the Buddhist caste system is not of Indian, but of Tibetan origin.

It is even more curious that even European Christian missionary preachers were drawn into the Indian caste system: those who preached the teachings of Christ to high-born Brahmins ended up in the Christian “Brahmin” caste, and those who communicated with untouchable fishermen became Christian untouchables.

9. You need to know the caste of the Indian you are communicating with and behave accordingly.

This is a common misconception, propagated by travel sites, for no known reason and not based on anything.

It is impossible to determine which caste an Indian belongs to just by his appearance, and often by his occupation too. One acquaintance worked as a waiter, although he came from a noble Rajput family (that is, he is a kshatriya). I was able to identify a Nepalese waiter I knew by his behavior as an aristocrat, since we had known each other for a long time, I asked and he confirmed that this was true, and the guy was not working because of a lack of money at all.

My old friend started his labor activity at the age of 9, as a laborer, he removed garbage from a shop... do you think he is a Shudra? no, he is a Brahmin (Brahmin) from a poor family and the 8th child... another Brahmin I know sells in a shop, he The only son, you have to earn...

Another friend of mine is so religious and bright that one would think that he is a real, ideal Brahmin. But no, he was just a sudra, and he was proud of it, and those who know what seva means will understand why.

And even if an Indian says what caste he is, although such a question is considered rude, it will still give nothing to the tourist; a person who does not know India will not understand what and why it works in this amazing country. So there is no need to be puzzled by the caste issue, because in India it is sometimes difficult to even determine the gender of the interlocutor, and this is probably more important :)

10. Caste discrimination in modern times

India is a democratic country and, in addition to prohibiting caste discrimination, has introduced benefits for representatives of lower castes and tribes, for example, there are quotas for admission to higher education institutions and for holding positions in state and municipal bodies.

discrimination against people from lower castes, Dalits and tribal people in India is quite serious, casteism is still the basis of life for hundreds of millions of Indians outside large cities, it is there that the caste structure and all the prohibitions arising from it are still preserved, for example, in some temples in India Indian Shudras are not allowed in, this is where almost all caste crimes take place, for example, a very typical crime

Instead of an afterword.

If you are seriously interested in the caste system in India, I can recommend, in addition to the articles section on this site and publications on the Hindunet, reading major European Indologists of the 20th century:

1. Academic 4-volume work by R.V. Russell "and the castes of the central provinces of India"

2. Monograph by Louis Dumont "Homo hierarchicus. Experience in describing the caste system"

Besides, in last years A number of books on this topic have been published in India, unfortunately I have not held them in my hands.

If you are not ready to read scientific literature, read the novel “The God of Small Things” by the very popular modern Indian writer Arundhati Roy, it can be found in RuNet.

CASTES, a term applied primarily to the major division of Hindu society in the Indian subcontinent. It is also used to designate any social group that adheres to strict norms of group behavior and does not allow outsiders into its ranks. The main characteristics of the Indian caste: endogamy (marriage exclusively between members of the caste); hereditary membership (accompanied by the practical impossibility of moving to another caste); prohibition on sharing meals with representatives of other castes, as well as having physical contact with them; recognition of the firmly established place of each caste in the hierarchical structure of society as a whole; restrictions on choosing a profession; autonomy of castes in regulating intra-caste social relations.

STORY

Origin of Varnas . From the earliest works of Sanskrit literature it is known that the Aryan-speaking peoples during the period of the initial settlement of India (from approximately 1500 to 1200 BC) were already divided into four main classes, later called “varnas” (Sanskrit “color”). : Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (traders, herders and farmers) and Shudras (servants and laborers).

Hindus believe in reincarnation and believe that those who follow the rules of their caste will rise to a higher caste by birth in a future life, while those who violate these rules will lose social status. See also METEMPSYCHOSIS.

Stability of castes . Throughout Indian history, the caste structure has shown remarkable stability in the face of change. Even the rise of Buddhism and its adoption as the state religion by Emperor Ashoka (269-232 BC) did not affect the system of hereditary groups. Unlike Hinduism, Buddhism as a doctrine does not support caste division, but at the same time it does not insist on the complete abolition of caste differences.

During the rise of Hinduism, which followed the decline of Buddhism, from a simple, uncomplicated system of four varnas, a complex multi-layered system grew, which built a strict order of alternation and correlation of different social groups. Each varna defined in the course of this process the framework for many independent endogamous castes (jatis). Neither the Muslim invasion, which ended with the formation of the Mughal Empire, nor the establishment of British rule shook the fundamental foundations of the caste organization of society. See also BUDDHA AND BUDDHISM; HINDUISM.

Castes in modern India . The Indian castes are literally countless. Since each named caste is divided into many sub-castes, it is impossible to even approximately calculate the number of social units possessing the minimum necessary characteristics of jati. The official tendency to downplay the importance of the caste system has led to the disappearance of the corresponding column in the once-a-decade population censuses. The last time information about the number of castes was published was in 1931 (3000 castes). But this figure does not necessarily include all local podcasts that operate as independent social groups.

It is widely believed that in the modern Indian state castes have lost their previous value. However, developments have shown that this is far from the case. The position taken by the INC and the Government of India after Gandhi's death is controversial. Moreover, universal suffrage and the need politicians in the support of the electorate they gave new importance to esprit de corps and internal cohesion of the castes. As a consequence, caste interests became an important factor during election campaigns.

NATURE OF CASTE

Brahmins. In a typical rural areas The highest layer of the caste hierarchy is formed by members of one or more Brahman castes, constituting from 5 to 10% of the population. Among these Brahmins there are a number of landowners, a few village clerks and accountants or accountants, and a small group of clergy who perform ritual functions in local sanctuaries and temples. Members of each Brahmin caste marry only within their own circle, although it is possible to marry a bride from a family belonging to a similar subcaste from a neighboring area. Brahmins are not supposed to follow the plow or perform certain types of manual labor; women from their midst can serve in the house, and landowners can cultivate plots, but not plow. Brahmins are also allowed to work as cooks or domestic servants.

A Brahman has no right to eat food prepared outside his caste, but members of all other castes can eat from the hands of Brahmans. When choosing food, a Brahmin observes many prohibitions. Members of the Vaishnava caste (who worship the god Vishnu) have adhered to vegetarianism since the 4th century, when it became widespread; some other castes of Brahmins who worship Shiva (Shaiva Brahmins) do not, in principle, renounce meat dishes, but abstain from the meat of animals included in the diet of the lower castes.

Brahmins serve as spiritual guides in the families of most high- or middle-status castes, except those considered "impure". Brahmin priests, as well as members of a number of religious orders, are often recognized by their “caste marks” - patterns painted on the forehead with white, yellow or red paint. But such marks indicate only membership in a major sect and characterize a given person as a worshiper of, for example, Vishnu or Shiva, and not as a subject of a particular caste or sub-caste.

Brahmins, more than others, adhere to the occupations and professions that were provided for in their varna. Over the course of many centuries, scribes, clerks, clergymen, scientists, teachers and officials emerged from their midst. Back in the first half of the 20th century. in some areas, brahmins occupied up to 75% of all more or less important government positions.

In communicating with the rest of the population, Brahmins do not allow reciprocity; Thus, they accept money or gifts from members of other castes, but they themselves never make gifts of a ritual or ceremonial nature. There is no complete equality among the Brahman castes, but even the lowest of them stands above the rest of the highest castes.

Kshatriyas. After the Brahmins, the most prominent hierarchical place is occupied by the Kshatriya castes. In rural areas they include, for example, landowners, possibly related to former ruling houses(for example, with the Rajput princes in North India). Traditional occupations in such castes are working as managers on estates and serving in various administrative positions and in the army, but now these castes no longer enjoy the same power and authority. In ritual terms, the Kshatriyas are immediately behind the Brahmins and also observe strict caste endogamy, although they allow marriage with a girl from a lower subcaste (a union called hypergamy), but in no case can a woman marry a man from a subcaste lower than her own. Most kshatriyas eat meat; they have the right to accept food from Brahmins, but not from representatives of any other castes.

Vaishya. The third category of "twice-born" castes includes merchants, shopkeepers and moneylenders. These castes recognize the superiority of the Brahmins, but do not necessarily show the same attitude towards the Kshatriya castes; as a rule, vaishyas are more strict in observing the rules regarding food, and are even more careful to avoid ritual pollution. The traditional occupation of Vaishyas is trade and banking; they tend to stay away from physical labor, but sometimes they are included in the management of the farms of landowners and village entrepreneurs, without directly participating in the cultivation of the land.

"Pure" Shudras. Members of the above "twice-born" castes constitute only a minority of the inhabitants of any rural area, while the majority of the agrarian population consists of one or more castes, called the "pure" Shudra castes. Although such castes are included in the fourth varna, this does not mean that they occupy the lowest stage in social hierarchy: There are many areas where the peasant caste, due to its numbers and ownership of a significant part of the local land, plays a vital role in resolving social and political issues. In ancient times, the Shudra peasant castes recognized the political dominance of the Kshatriyas who ruled the area, but today these relations are a thing of the past, and the superiority of the Kshatriya landowners is recognized only in ritual terms, and even then not always. Peasants employ Brahmins as family priests and market their produce through members of merchant castes. Individuals from “pure” sudras can act as tenants of plots from brahmanas, landowners, and merchants.

All peasant castes are endogamous, and even with approximately equal status, as is observed in many areas, out-of-caste marriages are not allowed. The rules regarding food intake among the farming castes are less strict than among the “twice-born”; they eat meat. Their regulations also leave much more space for social acts, allowing, for example, the marriage of widows and divorced women, which is strictly prohibited among the “twice-born”.

Lower Shudras. Below those Shudras who are engaged in agriculture are numerous castes whose profession is of a highly specialized nature, but is generally considered less respectable. These are the castes of potters, blacksmiths, carpenters, joiners, weavers, oil makers, distillers, masons, barbers, musicians, tanners, butchers, scavengers and many others. Members of these castes are supposed to practice their hereditary profession or craft; however, if a Shudra is able to acquire land, any of them can engage in agriculture. Members of many craft and other professional castes have traditionally had traditional relationships with members of higher castes, which consist of the provision of services for which no salary is paid, but an annual remuneration in kind. This payment is made by each household in the village whose requests are satisfied by a given member of the professional caste. For example, a blacksmith has his own circle of clients, for whom he makes and repairs equipment and other metal products all year round, for which he, in turn, is given a certain amount of grain.

The Untouchables. Those whose professions require physical touching of clients (such as barbers or people who specialize in washing clothes) serve members of castes higher than their own, but potters or blacksmiths work for the entire village, regardless of the caste of the client. Activities such as tanning leather or slaughtering animals are considered clearly polluting, and although this work is very important to the community, those who engage in it are considered untouchables. In many respects they are outside the boundaries of Hindu society, they were called "outcaste", "low", "scheduled" castes, and Gandhi proposed the euphemism "harijans" ("children of God"), which became widely used. Members of these castes are prohibited from visiting the houses of the “pure” castes and drawing water from their wells. Most Hindu temples until recently were closed to untouchables; there was even a ban on approaching people from higher castes closer than a set number of steps. The nature of caste barriers is such that Harijans are believed to continue to pollute members of the “pure” castes, even if they have long abandoned their caste occupation and are engaged in ritually neutral activities, such as agriculture. Although in other social settings and situations, such as being in an industrial city or on a train, an untouchable may have physical contact with members of higher castes and not pollute them, in his home village untouchability is inseparable from him, no matter what he does.

Economic interdependence . The various professional castes are economically interdependent, and their functions are complementary rather than competitive. Each caste has the right to perform certain jobs that other castes are prohibited from doing. Its members in any given locality usually form a closely knit group of relatives who do not compete to provide services to other castes, but by mutual agreement share the clientele among themselves. For this reason, they are in an advantageous position in relation to members of the castes at the top of the caste hierarchy, who are forbidden to change at their discretion the blacksmith, barber or person who washes their clothes.

Lack of competition does not apply to those cultivating the land. Although there are traditional peasant castes from which people will never become potters or weavers, tillage is not an exclusively hereditary occupation and a member of any caste can work the land. Wherever a group of artisans becomes too numerous and lacks a clientele, or where the advent of machine-made goods creates unemployment, those who can no longer live on the traditional trade tend to turn to peasant labor and become agricultural laborers or tenants.

The special patron-client relationship between the upper, land-owning castes and the professional castes of artisans and laborers is called the jajmani system. To jajman, which means patron-landlord in Hindi, people from other castes provide services in exchange for a certain amount of grain received annually.

Hierarchy. The rigid hierarchy and economic interdependence of castes have the closest connection with the fact that castes and sub-castes are endogamous and represent hereditary groups. However, in practice, a person from a high caste may be accepted into a lower caste; Thus, in the case of an unequal marriage between members of two different castes deviating from the rule, the person who is higher in status has no choice but to ask for his (or her) life partner. Such mobility is always unilinear and directed from top to bottom.

The idea of maintaining social distance between castes is based on the concepts of pollution and ritual purity. Many activities, from performing religious rites and offering prayers to cooking, are permitted only in a state of ritual purity. Thus, a person belonging to a high caste may be defiled not only by an intentional act, such as sexual intercourse with an untouchable, but also unintentionally, such as by eating food prepared by a person of lower ritual status, or even by sharing a meal with a person of another high caste, having, however, lost their ritual purity. Defilement is contagious, and the family or caste group must remain constantly vigilant against any contact with a potential carrier of defilement. Caste members in highest degree are intolerant of deviant behavior on the part of fellow caste members and excommunicate anyone who does not comply with accepted norms. Most castes have their own regional councils, which deal with issues affecting the welfare and especially the prestige of the caste. These councils also function as judicial bodies and have the power to investigate and punish misconduct, expelling the offender from the caste if necessary. Return to it is possible in all cases, except for particularly egregious ones, provided that the violator pays a fine and undergoes a purification ceremony. Being extremely strict regarding the observance of rules and prohibitions within their own caste, Hindus are usually tolerant of the norms of behavior accepted in other castes.

Indian caste system outside India . This system is widespread throughout the country, with the exception of a few marginal tribal areas such as Nagaland. It also prevails in much of Nepal, where immigrants from India brought with them a social order essentially replicating that of medieval India. The indigenous population of the main Nepalese cities where the Newars live is largely organized on a caste basis, but the idea of castes has not spread to the peoples of the mountainous regions and adherents of Tibetan Buddhism.

In Bangladesh, the caste system continues to operate among the remaining Hindus there, and even in the country's Muslim community there is a similar stratification.

In Sri Lanka, Sinhalese Buddhists and Tamil Hindus are also divided into castes. Although there are no Brahmins or other “twice-born” on the island, here, as in India, the division of labor along caste lines and mutual obligations of a ritual and economic nature are preserved.

Outside India, the ideas and practices inherent in the caste system prevail, often in a modified and weakened form, wherever significant numbers of Indians have settled, such as Malaysia, East Africa and Fiji.

Caste is the original civilizational model,

built on its own conscious principles.

L. Dumont “Homo Hierarchicus”

The social structure of the modern Indian state is unique in many ways, primarily due to the fact that, like several thousand years ago, it is still based on the existence of a caste system, which is one of its main components.

The word “caste” itself appeared later than the social stratification of ancient Indian society began. Initially the term "varna" was used. The word "varna" Indian origin and means color, manner, essence. In the later laws of Manu, instead of the word “varna”, the word “jati” was sometimes used, meaning birth, gender, position. Subsequently, in the process of economic and social development, each varna was divided into big number castes, in modern India there are thousands of them. Contrary to popular belief, the caste system in India has not been abolished, but still exists; Only discrimination on the basis of caste is abolished by law.

Varna

In ancient India there were four main varnas (chaturvarnya), or classes. The highest varna - brahmans - are priests, clergy; their duties included studying sacred texts, teaching people and performing religious rituals, since they were the ones who were considered to have the proper holiness and purity.

In ancient India there were four main varnas (chaturvarnya), or classes. The highest varna - brahmans - are priests, clergy; their duties included studying sacred texts, teaching people and performing religious rituals, since they were the ones who were considered to have the proper holiness and purity.

The next varna is the kshatriyas; these are warriors and rulers who had the necessary qualities (for example, courage and strength) to govern and protect the state.

They are followed by Vaishyas (merchants and farmers) and Shudras (servants and laborers). The attitude to the last, fourth varna is told in the ancient legend about the creation of the world, which says that at first three varnas were created by God - brahmanas, kshatriyas and vaishyas, and later people (praja) and cattle were born.

The first three varnas were considered the highest, and their representatives were “twice-born”. The physical, “first” birth was only a door to this earthly world, however, for internal growth and spiritual development, a person had to be born a second time - anew. This meant that representatives of privileged varnas underwent a special rite - initiation (upanayana), after which they became full members of society and could learn the profession that they inherited from representatives of their clan. During the ritual, a cord of a certain color and material, prescribed in accordance with the tradition of this varna, was placed around the neck of a representative of a given varna.

It was believed that all varnas were created from the body of the first man - Purusha: brahmanas - from his mouth (the color of this varna is white), kshatriyas - from his hands (the color is red), vaishyas - from the thighs (the color of varna is yellow), shudras - from his feet (black color).

The “pragmatism” of such a class division lay in the fact that initially, as is assumed, a person’s assignment to a certain varna occurred as a result of his natural inclinations and inclinations. For example, a brahmana became one who could think with his head (therefore the symbol is the mouth of Purusha), who himself had the ability to learn and could teach others. A Kshatriya is a person with a warlike nature, more inclined to work with his hands (that is, to fight, therefore the symbol is the hands of Purusha), etc.

Shudras were the lowest varna, they could not participate in religious rituals and study the sacred texts of Hinduism (Vedas, Upanishads, Brahmins and Aranyakas), they often did not have their own household, and they were engaged in the most difficult types of labor. Their duty was unconditional obedience to the representatives of the higher varnas. The Shudras remained “once-born,” that is, they did not have the privilege of rebirth to a new, spiritual life (probably because their level of consciousness was not ready for this).

Varnas were absolutely autonomous, marriages could only take place within a varna, the mixing of varnas, according to the ancient laws of Manu, was not allowed, as well as the transition from one varna to another - higher or lower. So tough hierarchical structure was not only protected by laws and tradition, but was directly connected with the key idea of the Indian religion - the idea of reincarnation: “As childhood, youth and old age come to the embodied here, so does a new body come: the sage cannot be puzzled by this” (Bhagavad Gita).

It was believed that being in a certain varna is a consequence of karma, that is, the cumulative result of one’s actions and deeds in past lives. The better a person behaved in past lives, the more chances he had in next life to incarnate in a higher varna. After all, varna affiliation was given by birth and could not change throughout a person’s life. This may seem strange to a modern Westerner, but a similar concept, completely dominant in India for several thousand years until today, created, on the one hand, the basis for the political stability of society, on the other, it was a moral code for huge sections of the population.

Therefore, the fact that the varna structure is invisibly present in the life of modern India (the caste system is officially enshrined in the main law of the country) is most likely directly related to the strength of religious convictions and beliefs that have stood the test of time and have remained almost unchanged to this day.

But is the secret of the “survivability” of the varna system only in the power of religious ideas? Perhaps ancient India managed to anticipate the structure in some way modern societies And is it not by chance that L. Dumont calls castes a civilizational model?

A modern interpretation of the varna division might look, for example, like this.

Brahmins are people of knowledge, those who receive knowledge, teach it and develop new knowledge. Since in modern “knowledge” societies (a term officially adopted by UNESCO), which have already replaced information societies, not only information, but knowledge is gradually becoming the most valuable capital, surpassing all material analogues, it becomes clear that people of knowledge belong to the highest strata of society .

Kshatriyas are people of duty, senior managers, government-level administrators, military personnel and representatives of the “security agencies” - those who guarantee law and order and serve their people and their country.

Vaishyas are people of action, businessmen, creators and organizers of their business, whose main goal is to make a profit; they create a product that is in demand in the market. Vaishyas now, just like in ancient times, “feed” other varnas, creating the material basis for the economic growth of the state.

Shudras are people for hire, hired workers, for whom it is easier not to take responsibility, but to carry out the work assigned to them under the control of management.

Living “in your varna,” from this point of view, means living in accordance with your natural abilities, innate predisposition to a certain type of activity and in accordance with your calling in this life. This can give a feeling of inner peace and satisfaction that a person is living his own, and not someone else’s, life and destiny (dharma). It is not for nothing that the importance of following one’s dharma, or duty, is spoken of in one of the sacred texts included in the Hindu canon - the Bhagavad Gita: “It is better to fulfill one’s duties, even imperfectly, than the duties of others perfectly. It’s better to die doing your duty; someone else’s path is dangerous.”

In this “cosmic” aspect, the varna division looks like a completely pragmatic system for realizing a kind of “call of the soul”, or, in higher language, fulfilling one’s destiny (duty, mission, task, calling, dharma).

The Untouchables

In ancient India there was a group of people who were not part of any of the varnas - the so-called untouchables, who de facto still exist in India. The emphasis on the actual state of affairs is made because the situation with the untouchables in real life is somewhat different from the legal formalization of the caste system in modern India.

The untouchables in ancient India were a special group that performed work associated with the then ideas about ritual impurity, for example, dressing animal skins, collecting garbage, and corpses.

In modern India, the term untouchables is not officially used, as are its analogues: harijan - “children of God” (a concept introduced by Mahatma Gandhi) or pariah (“outcast”) and others. Instead, there is a concept of Dalit, which is not believed to carry the connotation of caste discrimination prohibited in the Indian Constitution. According to the 2001 census, Dalits constitute 16.2% of India's total population and 79.8% of the total rural population.

Although the Indian Constitution has abolished the concept of untouchability, ancient traditions continue to dominate the mass consciousness, which even leads to the killing of untouchables under various pretexts. At the same time, there are cases when a person belonging to a “pure” caste is ostracized for daring to do “dirty” work. Thus, Pinky Rajak, a 22-year-old woman from the caste of Indian washerwomen, who traditionally wash and iron clothes, caused outrage among the elders of her caste because she began cleaning at a local school, that is, she violated the strict caste ban on dirty work, thereby insulting her community.

Castes Today

To protect certain castes from discrimination, there are various privileges given to citizens of lower castes, such as reservation of seats in legislatures and public service, partial or full tuition fees in schools and colleges, quotas in higher education educational institutions. In order to avail the right to such a benefit, a citizen belonging to a state-protected caste must obtain and present a special caste certificate - proof of his membership in a particular caste listed in the caste table, which is part of the Constitution of India.

Today in India, belonging to a high caste by birth does not automatically mean high level material security. Often, children from poor families of upper castes who enter college or university on a general basis with big competition, are much less likely to receive an education than children from lower castes.

The debate about actual discrimination against upper castes has been going on for many years. There are opinions that in modern India there is a gradual erosion of caste boundaries. Indeed, it is now almost impossible to determine which caste an Indian belongs to (especially in large cities), and not only by appearance, but often also by the nature of his professional activity.

Creation of national elites

The formation of the structure of the Indian state in the form in which it is presented now (developed democracy, parliamentary republic) began in the 20th century.

In 1919, the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms were carried out, the main goal of which was the establishment and development of a system of local government. Under the English governor-general, who had previously virtually ruled the Indian colony single-handedly, a bicameral legislative body was created. In all Indian provinces, a system of dual power (diarchy) was created, when both representatives of the English administration and representatives of the local Indian population were in charge. Thus, at the very beginning of the twentieth century, democratic procedures were introduced for the first time on the Asian continent. The British, unwittingly, contributed to the formation of the future independence of India.

After India gained independence, the need arose to attract national personnel to lead the country. Since only the educated sections of Indian society had real opportunity“restart” of public institutions under conditions of independence, it is clear that the leading role in governing the country mainly belonged to the brahmanas and kshatriyas. That is why the unification of the new elites was practically conflict-free, since the brahmins and kshatriyas historically belonged to the highest castes.

Since 1920, the popularity of Mahatma Gandhi, who advocated a united India without the British, began to grow. The Indian National Congress, which he headed, was not so much a party as a national social movement. Gandhi managed to accomplish something that no one had succeeded before - albeit temporarily, but he practically eliminated the conflict of interests between the higher and lower castes.

What tomorrow?

In India in the Middle Ages there were no cities similar to European ones. These cities could rather be called large villages, where time seemed to stand still. Until recently (especially intensive changes began to occur in the last 15–20 years), tourists coming from the West could feel themselves in a medieval atmosphere. Real changes began after independence. The course towards industrialization taken in the second half of the twentieth century caused an increase in the rate of economic growth, which, in turn, led to an increase in the share of the urban population and the emergence of new social groups.

Over the past 15–20 years, many Indian cities have changed beyond recognition. Most of the almost “homey” neighborhoods in the center turned into concrete jungles, and the poor neighborhoods on the outskirts were transformed into residential areas for the middle class.

According to forecasts, by 2028, India's population will exceed 1.5 billion people, the largest percentage of them will be young people and, compared to Western countries, the country will have the largest population labor resources.

Today, in many countries there is a shortage of qualified personnel in the field of medicine, education and IT services. This situation has contributed to the development in India of such a rapidly growing sector of the economy as the provision of remote services, for example, the United States and countries Western Europe. The Indian government is now investing heavily in education, especially in schools. You can see with your own eyes how in the mountainous regions of the Himalayas, where 15-20 years ago there were only remote villages, state technological colleges have grown up in large areas, with beautiful buildings and infrastructure, intended for local children from the same villages. The bet on education in the age of “knowledge” societies, especially on school and university education, is a win-win, and it is no coincidence that India occupies one of the leading places in the field of computer technology.

This projection of Indian population growth could be optimistic for India and lead to significant economic growth as well. But growth doesn't happen by itself. It is necessary to create conditions: new jobs, ensuring industrial employment and, no less important, providing qualified training to all this huge mass of human resources. All this is not an easy task and rather a challenge for the state, rather than a bonus. If the necessary conditions are not met, there will be mass unemployment, a sharp decline in the living standards of the population and, as a consequence, negative changes in social structure.

Until now, the existing caste system has been a kind of “fuse” against various kinds of social upheavals throughout the country. However, times are changing, Western technologies are intensively penetrating not only the Indian economy, but into the consciousness and subconscious of the masses, especially in cities, forming a new, non-traditional for many Indians model of desires according to the principle “I want more now.” This model is intended primarily for the so-called middle class (“so-called” because for India its boundaries are blurred and the criteria for membership are not entirely clear). The question of whether the caste system can still serve as a protector against social cataclysms in the new conditions remains open.

Dating back to the ancient Indian varnas and sanctified by Hinduism, the caste system has been the basis of the social structure of India since ancient times. Belonging to one caste or another was associated with a person’s birth and determined his status for his entire life. At times, life introduced amendments to the rigid scheme: the rulers of states and principalities coming from among the Shudras acquired the status of a kshatriya. The same status was acquired by those foreigners who, like the Rajputs, remained primarily warriors and thereby performed the functions of the ancient kshatriyas. In general, the varna-caste status of the kshatriyas, more than others determined by political and therefore very dynamic factors, was in this sense quite flexible. The hereditary status of the brahmans was much more rigid: it was very difficult to lose it, even when the brahman ceased to be a priest and was engaged in other, much more worldly affairs, but it was even more difficult, almost impossible, to gain again. As for the Vaishyas and Shudras, the difference between them in the hierarchy of statuses has been decreasing since ancient times and was practically now small, but the line has changed somewhat: the Vaishyas began to predominantly belong to the castes of traders and artisans, and the Shudras - farmers. The proportion of outcaste outcasts, untouchables (harijans, as they were called later), who performed the most difficult and dirty work, increased greatly.

The Varna caste system as a whole, precisely because of its rigid hierarchy, formed the backbone of the social structure of India; unique in form, it not only turned out to be an effective alternative to a weak political administration (and perhaps vice versa: its uniqueness gave rise to and determined the weakness of the state administration - why do we need a strong administrative system if there is no lower level, if the lower classes live according to the laws self-regulating caste principles and communal norms?), but also successfully compensated for this weakness, although this kind of compensation, as already discussed, did not in any way contribute to the political stability of states in India. However, society as a whole did not suffer from this instability - this is how traditional India differed favorably from both Islamic states and the Far East, where the crisis of the state invariably affected the well-being of society.

The fact is that the Varnov-caste system, despite any political upheavals, very successfully maintained an unshakable status quo in the lower levels of society. Of course, society was not indifferent whether there were wars or not; The Indian lower classes, as elsewhere, suffered a lot from them. And the point is not that society prospered when states waged armed struggle with each other for power. What is meant is something else: this struggle did not lead to a crisis in the social structure and did not coincide with anything of that kind. And the top political struggle for power did not noticeably affect the bulk of Indians. And here not only the Varna-caste system played an important role, but also the traditional Indian community, built on the basis of the same system.

The communal form of organization of farmers is universal. The specificity of India was not the very fact of the existence of a community there, even a strong one, but the place that this community, thanks to the existence of the Varna-caste system, occupied in the social and economic structure of society. IN in a certain sense we can say that the structure of the Indian community and its internal connections were an indestructible microcosm of Indian society, which, in turn, as a macrocosm, copied this structure. What was this cell reduced to?

The traditional Indian community in its medieval modification was, especially in the south, a complex social entity. Geographically, it usually included several neighboring villages, sometimes an entire district, organizationally united into something single. Each village had its own headman, often a community council (panchayat), and representatives of each village, headmen and members of the panchayat, were part of the community council of the entire large community. In the north of the country, where communities were smaller, they could consist of one large village and several neighboring small villages adjacent to it and have one headman and one community council. Headed by a council, often elected from among the farmers of one caste that was dominant in a given area, the community was a kind of self-regulating mechanism or, more precisely, a social organism that practically did not need contact with the outside world. Inner life communities, strictly regulated by the norms of communal routine and caste relationships, were subject to the same principle of jajmani, studied by specialists relatively recently using the example of a rather late Indian community, but clearly rooted in ancient times. Its essence boiled down to a strictly obligatory reciprocal exchange, to a strictly and clearly regulated order for centuries in the mutual exchange of products and services necessary for everyone within the closed framework of the community - in mandatory compliance with the norms of the Varna-caste hierarchy.

The community was dominated by its full members, communal farmers, who owned communal plots and had hereditary rights to them. The allotments could be and were different. Each family, large or small, farmed individually on its own plot, which could sometimes even be alienated, although under the control of the community. Not all landowners in the community cultivated their plots themselves. The wealthiest families, most often Brahman families, used the labor of their land-poor neighbors, renting out their land to them. The labor of inferior members of the community, mercenary farm laborers (karmakars), etc. was also used for this. Needless to say, the poor and disadvantaged, tenants, and especially farm laborers, most often belonged to the lower castes. Moreover, the entire caste system of compulsory reciprocal exchange (jajmani) was primarily aimed at sanctifying and legitimizing social and property inequality in the community, as well as in society as a whole. Representatives of the upper castes had, according to established norms, the undeniable right to use, literally for pennies, the services of people from lower castes and, especially, untouchables, who should also be treated with contempt. And what is characteristic: such a right has never been subjected to even a shadow of doubt by anyone. This is necessary, this is the norm of life, the law of life. This is your destiny, such is your karma - both the upper caste community and the caste and non-caste lower classes lived with this consciousness.

In practice, the jajmani principle meant that every member of the community - be he a farmer, a farm laborer, a rich Brahmin, an artisan, a despised cattle slaughterer or scavenger, a washerman, etc. - in a word, each in his place and in strict accordance with his caste position should was not only clearly aware of his place, rights and responsibilities, but also strictly fulfilled everything that others had the right to expect from him. Actually, this is what made the community self-regulating and viable, almost independent of contacts with the outside world. At the same time, the jajmani principle did not mean at all that everyone who uses the labor, products and services of others himself pays for it in an equivalent way - especially with those who gave or did something to him. More often than not, the situation was just the opposite: everyone fulfilled his duties, serving everyone else, giving to others what he had to give, and at the same time receiving the products and services necessary for his life (in accordance with the caste-determined quality of his life). Outside the jajmani system, the community had only private transactions such as renting or hiring a farm laborer. Everything else was tightly tied to this traditional system of mutual obligations in strict accordance with the caste duties and position of each of those who lived in the community.

Led the entire complex system internal relations, the community council, which also examined complaints, held court, passed sentences, i.e., was simultaneously both the governing body of the corporation (community) and the local authority. The headman played a significant role in the council, whose prestige was high, and usually his income as well. For the outside world, and in particular for the administrative-political and fiscal system of the state, it was the headman who was both a representative of the community and an agent of local authorities, responsible for the payment of taxes and order.

The organization of Indian cities was also a kind of variant of the communal caste system. In the cities, castes played, perhaps, an even greater role than in the communal village - at least in the sense that the communities here were usually single-caste, that is, they completely coincided with the castes, be it a guild of representatives of some craft or a guild of merchants . All artisans and traders, the entire working population of the city were strictly divided into castes (castes of weavers, gunsmiths, dyers, traders of vegetable oil, fruits, etc.), and representatives of related or related castes and professions were often united into larger specialized shreny corporations, also headed by boards and executives responsible to the authorities. Indian crafts - weaving, jewelry, etc. - were famous throughout the world. Trade connections connected Indian cities with many countries. And in all these connections, the huge, decisive role was played by the castes and corporations of urban artisans and traders, who decided all issues and regulated the entire life of their members, from rationing and quality of products to litigation and donations to temples.

Tsarevo █ Church of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker Tsarevo parish festive service June 05

Revival of the Sergius Church

Annexation of the Crimean Khanate to Russia Abolition of duties and the mint

Church of St. Dmitry the Myrrh-Streaming in the field

Group Bible Reading and Study Time of Voluntary Infirmity