Most Moscow museums are closed on Mondays, but this does not mean that the public does not have the opportunity to experience beauty. Especially for the first working day of the week, the editors of the online publication launched a new section “10 Unknowns”, in which we introduce you to ten works of world art, united by one theme. Print out our guide and feel free to take it to the museum starting Tuesday.

An exhibition of artist Leonid Sokov “Unforgettable Meetings” opened at the Tretyakov Gallery on Krymsky Val. According to the plan of the curator and author, 46 works by Sokov were scattered throughout permanent exhibition Soviet art. Thanks to this decision, the meaning of both has changed.

Leonid Sokov "Vitruvian Bear", 2016

“Unforgettable Meetings” is an exhibition-excursion that Leonid Sokov conducts for visitors Tretyakov Gallery. Through his objects he builds dialogues with the most significant works Soviet art from avant-garde to social art, as well as with images of world classics.

Sokov began working as an artist and animal sculptor under the guidance of teachers of the Moscow Secondary Art School Vasily Vatagin and Dmitry Tsaplin, as well as under the influence of European modernist sculpture of the early 20th century. These animalistic drawings and sculptures soon turned into symbolic signs. The work “Vitruvian Bear,” although completed in 2016, refers precisely to that early style of the artist’s works. On the one hand, this is an allusion to the “Vitruvian Man” by Leonardo da Vinci, perhaps himself famous drawing Italian Renaissance, on the other hand, the bear, whatever one may say, is one of the most popular symbols of Russia, its national element. And in Sokov’s work the bear becomes an important character.

Leonid Sokov "Two-headed crow in Letatlin", 2013

At the exhibition you can find comments from the author himself, which are often missing at exhibitions. contemporary art. About Letatlina Sokov says that this design is an illustrative example of the 1917 revolution. “The idea is very Russian: man is born for happiness, like a bird is born for flight.” The representative of the avant-garde, Vladimir Tatlin, and his projects became the brainchild of the revolution in the sense that it was the revolution, as it seemed, that would make man free and pave the way for him not only into space, but also to general prosperity. Tatlin worked on a project for an aircraft for the military department, which was propelled by human muscle power. But it didn’t work out to fly, just as it didn’t work out to realize the ideas of a new society. And the two-headed crow serves as a parody of the eagle, belittling the imperial ambitions of the symbol of the new Russia.

Leonid Sokov "Shirt", 1973

Leonid Sokov "Shirt", 1973

Sokov turns not only to visual images, but also to language. In Russian folklore there is a saying “to sew a wooden shirt,” that is, to put together a coffin. At the same time, this work contains a reference to world art, in particular to pop art, in which everyday consumer objects made in various techniques and materials, were immortalized in art objects.

Leonid Sokov "Glasses for everyone" Soviet man", 2000

The work "Glasses for every Soviet person" was completed in 2000, but falls out of modern context. It is directly related to the ideas of social art of the 1970s. In the Russian language there is an expression “to look at the world through rose-colored glasses,” that is, to be deceived, not to notice shortcomings. These “glasses” were imposed on Soviet people through ideas and propaganda. The symbol of the era is the red stars carved into Sokov’s wooden glasses.

Leonid Sokov "Dyr bul schyl" Kruchenykh", 2005

The “abstruse” poem “Dyr bul schyl” by Alexei Kruchenykh, written in 1912, became, along with Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square”, one of the most important symbols of the Russian avant-garde. According to the author, there was “more Russian nationality in him than in all of Pushkin’s poetry.” Sokov takes the poem into the context of the 1960-70s, when conceptual artists again returned to texts as a means of visual expression. “I can’t, like conceptualists, type something on a typewriter,” explains the author. “I wanted to record my admiration for the brilliant poem of the Kruchenykhs in space.”

Leonid Sokov "HERE", 2016, repetition of the work of 1978

“HERE” essentially also serves as a reference to Russian literature. Sokov took it from his contemporary, the poet Vsevolod Nekrasov. According to the artist, this word covered the situation of the 1970s and 80s and became its essential characteristic, because we say “here” when there is nothing else to say. And at that moment there was really nothing more to say: the era of the USSR was coming to an end.

Leonid Sokov "Meeting of two sculptures", 1994

One of the most interesting and subtle works of the artist is a play of meanings. Firstly, the sculpture of Lenin, which was reproduced millions of times, has become the same symbol Soviet era, like “The Walking Man” by Anthony Gomrley for Western European culture. Secondly, this is not just a “Meeting of two sculptures” from parallel realities, but also a meeting of two worldviews that do not intersect in space.

Leonid Sokov "Viewing angle", 1976

The abstract composition “Angle of View” again refers to the works of Kazimir Malevich or Alexander Rodchenko. It is composed of Suprematist elements and is supplemented with an inscription that could become the name of some creative association 1920s On the other hand, the material itself (wood) gives rise to an association with primitive art.

Leonid Sokov "Stalin and Monroe", 2008

Images of Stalin and Monroe were replicated in the USSR and the USA with approximately equal zeal. These cultural symbols of the era, opposite in essence, eventually turned into endlessly repeated and meaningless signs. Therefore, for Sokov, combining these signs in the space of one image was a completely logical move. According to the artist, in 300 years, when the world has forgotten the real historical context, everyone will believe his works and think that such a meeting really took place in history, just as we believe everything that is depicted in Renaissance paintings.

Leonid Sokov "Where did the aggression of the Russian avant-garde go?", 2002

The works of Kazimir Malevich still serve as an inexhaustible source of inspiration for Sokov. He rethinks them, trying to use their example to understand the evolution of the Russian avant-garde. “It was in the 1930s that Stalin began to build the Soviet military machine. the best minds and talents Soviet Union, says Sokov. – Look at the predatory hawk-like design of Soviet military aircraft from the 1930s, with their noses up and their landing gear extended like paws birds of prey. Or tank towers, the design of which contains a square, a triangle and a rhombus." Sokov says that the aggression of the Russian avant-garde was embodied in military equipment and creates an object whose shape simultaneously resembles a porcelain teapot in the spirit of the works of Malevich or Rodchenko and a tank with a turret and muzzle.

Cloud of "Juice". 1999. Oil on canvas.

The museum continues to introduce viewers to creativity major artists, our contemporaries, who determine the originality of the domestic cultural landscape second half of the twentieth century - beginning of the XXI century. The special project of Leonid Petrovich Sokov (born 1941), a sculptor and one of the leaders of Sots Art, is fundamentally different from the traditional monographic show. The master’s works are dispersed throughout the permanent exhibition “Art of the 20th Century” - from the halls of the early avant-garde to socialist realism 1940-1950s, bringing the irony of postmodernism into these spaces.

Thus, Sokov acts as a guide, commentator and interpreter of the Tretyakov Gallery collection, pointing out artists close to him, emphasizing the most important works, movements and periods. The special project is the result of the author’s reflections on the artistic searches of the masters of Russian art of the last century and at the same time - self-reflection, an attempt to understand one’s own plastic experience, its origins, specifics and patterns.

Conspiracy against the evil eye. 2012. Wood, charcoal, water, oil paint.

The museum is open to such experimental shows. In 2015, a special project by the largest Moscow conceptualists I. Makarevich and E. Elagina was presented in the halls of post-war art. Such projects make the usual exhibition alive and moving, update and analyze it, offering new points of view, and also raise issues of museumification of contemporary art.

During his years of study at the Moscow Secondary Art School and the Moscow Higher Art and Industrial School (formerly Stroganov), Sokov painted a lot at the Moscow Zoo, honing his skills, his ability to “grab” the characteristic features of living nature and generalize what he saw, discarding the unnecessary to achieve the greatest expressiveness. Like many Soviet sculptors, Sokov was influenced by Alexander Matveev - the teacher of his teachers. After graduating from college, Sokov became a member of the Moscow Union of Artists, and then a member of the bureau of the sculpture section. But he was too cramped within the boundaries established for the Soviet artist. He quickly evolved - the budding animal painter was interested in modern Western plastic arts and participated in unofficial exhibitions. A distinctive feature of his works was the ironic play of quotes, symbols and allegories. In 1979, the sculptor emigrated from the USSR.\

Searching with a flashlight in the light of the sun. 2010. Casting, garth.

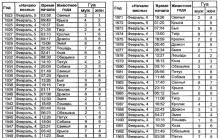

Now the Tretyakov Gallery houses about 30 works by Sokov. The first, in 1993, the museum received a gift from the author of the work “Stalin with a Bear’s Leg” (1993), in 1996 - “Toucan” and “Serval” (both 1971) from the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation. In the early 2000s, “Portrait of a Bureaucrat” (1984) and “Glasses (Glasses for Every Soviet Person)” (2000, the author’s repetition of a 1976 work) were received, the latter being works from the collection of the Soviet underground by Leonid Talochkin, transferred to the museum in 2014 .

In addition to works from the Gallery’s collection, the special project also includes works from the private collections of Dmitry Volkov, Shalva Breus, Ekaterina and Vladimir Semenikhin, Vladimir Antonichuk, Simona and Vyacheslav Sokhransky, which are important for revealing the theme.

According to Sokov, the special project “Unforgettable Meetings” does not pretend to be an active “invasion” or “intervention” of his works into the Gallery’s exhibition. Rather, it is an attempt by the sculptor to “blend” with those who influenced him and whom he loves. These are the leaders of the Russian avant-garde - Mikhail Larionov, Vladimir Tatlin, Kazimir Malevich, and the teacher of his teachers - Alexander Matveev. Especially for this show, the curators removed from the museum's storerooms rarely exhibited works by sculptors especially significant to Sokov - Vasily Vatagin, Alexander Matveev, Dmitry Tsaplin - and supplemented them with the permanent exhibition.

Shirt. 1973-1974. Tree.

Introducing his favorite artists to the viewer, Sokov shows how his own works were created in dialogue with them, in imitation or in opposition - from animal paintings and female nudes of the 1960s to ironic objects and installations of the 1990s-2010s. In the hall with Vasily Efanov’s painting “An Unforgettable Meeting” (1936-1937), Alexander Gerasimov’s painting “I.V. Stalin and K.E. Voroshilov in the Kremlin" (1938) and other large-format works of socialist realism include Sokov's work "Meeting of two sculptures. Lenin and Giacometti" (1994) is one of the iconic works of social art. An installation is also presented here: Stalin “performs” in front of a modernist sculpture - miniature replicas of the most famous works Western masters of the twentieth century. The dialogue of diametrically opposed semantic and plastic systems reveals Sokov’s main method - the ironic and absurdist deconstruction of familiar symbols, signs, and clichés.

As part of a special project, one of the most paradoxical objects Sokova is a life-size reproduction of a truck with Malevich’s suprematist coffin in the back and the “Black Square” on the hood. The truck, made of wood, resembles a giant children's toy, created in the tradition of Russian carved crafts. In combining interest in the avant-garde and folk tradition, archaic, primitive consists most important feature creative method Sokova.

Trying to understand the nature of popular consciousness and humor, Sokov discovered his predecessors among the artists of the Russian avant-garde, who drew energy and plastic ideas from the “grassroots” fairgrounds. cultural tradition. Therefore, it is no coincidence that the special project begins with Sokov’s objects in the halls of Mikhail Larionov, one of the main innovators of the Russian art scene the beginning of the last century. Sokovsky ironic hybrid objects became images of the collapse of the utopian ideas and plans of the first Russian avant-garde: a tank turret attached to Malevich’s Suprematist teapot, a crow in “Letatlin”, a stool erected above an architect.

Sokov’s most important character, the bear, one of the most recognizable symbols of Russia, took the place of the ideal human figure in the famous “Vitruvian Man” by Leonardo da Vinci. This “Vitruvian Bear” became the emblem of the project. Mobiles with bears, made in tradition folk toys, specially for the project, were released in a small edition and, together with other toy mobiles, will be available in gift shop.

Address: Krymsky Val, 10.

Directions to the station metro station "Park Kultury" or "Oktyabrskaya".

Operating mode: Tuesday, Wednesday, Sunday - from 10.00 to 18.00

(box office and entrance to the exhibition until 17.00)

Thursday, Friday, Saturday - from 10.00 to 21.00

(box office and entrance to the exhibition until 20.00)

day off - Monday

Ticket price: Adult - 500 rub. Preferential - 200 rubles. Read more.

With this ticket you can visit not only this exhibition, but also a permanent exhibition and other temporary exhibitions taking place at this time in the museum.

Every Wednesday, admission for individual visitors is free for the permanent exhibition and temporary exhibitions other than the exhibition.

Posts from This Journal by “GTG” Tag

Exhibition "Sculptor Anna Golubkina" - report.

Exhibition "Sculptor Anna Golubkina" - report.The exhibition “Sculptor Anna Golubkina” opened in the halls of the Tretyakov Gallery on Lavrushinsky Lane. Display of Golubkina’s works in…

Press conference of the Tretyakov Gallery.

Press conference of the Tretyakov Gallery.On Monday, May 20, a press conference was held dedicated to the restoration of Ilya Repin’s painting “Ivan the Terrible and his son Ivan November 16, 1581...

Exhibition "Head on the wall Paintings and graphics by B.A. Golopolosov 1920–1930s."

Exhibition "Head on the wall Paintings and graphics by B.A. Golopolosov 1920–1930s."Along with retrospectives of major Russian painters, the Tretyakov Gallery considers its most important mission to hold artist exhibitions,…

Exhibition "Semyon Faibisovich. Retrospective"

Exhibition "Semyon Faibisovich. Retrospective"The Tretyakov Gallery opens an exhibition of works by Semyon Faibisovich, one of prominent representatives art of the era of stagnation, perestroika and...

-

Since the 1970s, sculptor Leonid Sokov has been researching Soviet mythology, choosing for his sculptures typical images of Russian visual culture and transferring them to other environments, either comparing incompatible artistic traditions, or relocating the idols of society into the field of toy, pseudo-folk art. Brian Droitkur met with the sculptor in his New York studio to ask the master about the Moscow seventies that shaped him, his mentors and the art that inspired him, including Russian folklore.

Leonid Sokov. Photo: Alexandra Lerman, 2009

Brian Droitkur: Are you the only artist in your family?

Leonid Sokov: Yes. I was born in the village of Mikhalevo, in the Tver region. Before the war, my father was the director of a regional dairy plant; in 1941 he went to the front and died. I've never seen him. Mom raised two sons. In 1951, our house burned down, and my mother moved to Moscow.

B.D.: Was she proud that you entered the Stroganov School?

L.S.: Yes, sure. But before Stroganovka, I studied at the Moscow Secondary Art School from the age of 13. Along with general education subjects, every day there are 4 hours of sculpture, drawing, and painting. After graduating from MSHS I was already infected with bacilli artistic culture. Stroganov was a continuation of my studies, but the principles of my formation as an artist were laid down in the Moscow Art School. Interestingly, a circle of like-minded people has formed from the artists who graduated from the Moscow Art School, with whom I have been friends for about forty years. Yes, my mother was happy that I wasn’t fooling around and didn’t spend time in the alley with punks. But she did not submit documents for admission to art school for a long time - in her understanding, all artists were drunkards and unfounded people.

B.D.: How did your career develop after Stroganov?

L.S.: Many unofficial artists made money by illustrating children's books, and I sculpted animals for sculpture factories and designed children's playgrounds. Most often these were fairy tales: “The Fox and the Rooster”, “The Bear is a Lime Leg”, “The Goat and the Cabbage”. In the Moscow Union of Artists I became known as good animal painter, and they willingly gave me orders to depict animals. Having molded the next beast, it was possible for six months, without thinking about money, to calmly do things “for myself.”

Leonid Sokov. Taste of milk (Cow). 2007. Wrought iron, galvanized gold, cast iron, bell with swinging tongue. Source: official website of Leonid Sokov www.leonidsokov.org

B.D.: Why didn’t you like to sculpt people?

L.S.: These were not people. These were Marxes, Lenins, soldiers, pioneers. This contingent had to be made according to certain rules that existed in the sculpture plant: in which hand Lenin should hold his cap, how long the pioneer’s underpants should be, what kind of support leg Marx should have. It was disgusting to even think about these topics. I would love to make Lenin the way I wanted, but what artistic council would accept this? And who would pay for it? Although they paid three times less for a goat than for a Lenin figure of the same size.

B.D.: But you could sculpt the goats the way you wanted.

L.S.: Not right away. After graduating from Stroganovka, I was given my first order - for the park sculpture “Goat”. I was then fascinated by the wonderful 19th century sculptors Pimenov and Demut-Malinovsky, who often worked together. One of monumental sculptures Demut-Malinovsky - bulls that then stood in front of meat slaughterhouses in St. Petersburg. These bulls had huge eggs hanging between their legs like bells in an arch. I hung the same “bells” for my goat and considered it a successful “artistic find.” The artistic council has arrived. The men were discussing seriously, the ladies were giggling, I naively did not understand anything. My first order was not accepted. The secretary of the artistic council advised us to invite the then famous animal painter [George] Popandopulo. He immediately realized the “plastic mistake” of the young talent. When I unrolled the oilcloth on the goat sculpture, he immediately took hold of the eggs with his left hand and scooped up liquid clay into his right hand. Then he looked at me questioningly - I didn’t understand, I shrugged. Popandopulo pulled down: “And there might be wool here,” and right hand dashingly covered up the resulting empty place liquid clay. Afterwards he reported to the artistic council that he had accepted the work. In general, the first order from young people was always accepted with great difficulty. As one artist told me, his first commission, a children's book in which the main character was a hare, was accepted 16 times until the hare was drawn to meet all possible requirements. officials from director to publishing house fireman.

My career at Moscow Union of Artists was very successful. I had a subsidized workshop in the center of Moscow, I was accepted as a member of the Moscow Union of Artists, and later in the bureau of the sculpture section, they willingly gave orders for sculpting animals and appreciated me for my professional quality sculptor.

Leonid Sokov. Lenin and the new Russian. 1999. Wood, metal with rust. Source: official website of Leonid Sokov www.leonidsokov.org

BD: Why did you emigrate if you had such a good career?

L.S.: I mentioned one of the reasons. If we look at the case of the goat from the point of view of Sigmund Freud, then this is an unambiguous example of castration of the artist. And if I had not left, this probably would have happened. First “oink”, then “oink-oink”, then “oink-oink-oink”. Often very talented artists MOSKH, who worked to order, turned into mediocre sculptors before my eyes. In the 1970s, when I was in Moscow, there were 500 sculptors in the sculpture section of the Moscow Union of Artists alone. Can you name any of them who would be included in the modern anthology of sculpture or somehow appeared at the international level? Then I remembered the masters of the Russian avant-garde of the 1920s: Malevich, towards the end of his life, painted pioneers in realistic manner, Filonov painted portraits of Stalin and meticulously painted the machines in the factory workshop, and Tatlin created realistic still lifes. Mayakovsky, after a six-month trip to Paris or New York, reported with another poem: “Two in the room: me and Lenin in a photograph on a white wall.” These were brilliant artists and poets who broke one way or another. At that time I was interested in the question of the artist’s fulfillment. Before my eyes was the sad example of many avant-garde artists of the 1920s: Popova, Klyun, Ermilov, Rozanova, Mansurov, Stepanova, Chashnik, Kogan - all of them were poorly realized, but wonderful artists.

Leonid Sokov. Where did the aggression of the Russian avant-garde go? 2002. Ready-made. Porcelain, metal. State Tretyakov Gallery. Exhibit of the exhibition “Leonid Sokov. Unforgettable meetings" (2016-2017). Courtesy press service of the State Tretyakov Gallery

Since the early 1970s, exhibitions of unofficial art have been held in various research institutes and clubs. "" set the tone. She was the first and showed that art free from social order had appeared in Russian culture. But this was not a display of paintings to spectators, but a demonstration of unofficial artists against the existing order. Later, I was also invited to similar exhibitions, but I did not agree. I wanted to show my work not as a political gesture, but as an artistic one. In May 1976, I was offered to participate in an apartment exhibition, I agreed with the condition that it would be organized in my studio and I would curate it myself. And it took place in my studio and became one of seven apartment exhibitions that took place at that time in Moscow. It opened on May 10th. People from Bolshoy Sukharevsky Lane poured into the workshop. It was a fresh show for Moscow both in the sense of new names in unofficial art and in the sense of fresh ideas in the works. Everyone liked what we showed. As an artist and as the curator of the exhibition, I understood that I had hit the mark and received the approval of those whose opinions I valued. When I started making the exhibition, I didn’t expect similar results. Now it is clear that thanks to her, it was possible to transform the protest of unofficial artists into a display of works that were interesting from an artistic point of view. The exhibition had to be closed after 10 days - a local police officer began to come and ask why so many people were coming to the workshop. To hold an exhibition, permission was needed, and I said that I was just showing the work to friends. The experience of setting up an unofficial exhibition in my studio prompted me to leave. I wanted to do my own thing, and not sort things out with the authorities: why I do this or that work and why I show it. I was not a dissident, and I had no desire to fight the Soviet regime. I wanted to do my work the way I saw fit.

Leonid Sokov. Shirt. 1973-1974. Tree. State Tretyakov Gallery. Exhibit of the exhibition “Leonid Sokov. Unforgettable meetings" (2016-2017). Courtesy press service of the State Tretyakov Gallery

B.D.: How can you characterize your early unofficial works of the 1970s?

L.S.: At that time I was interested in the sculpture of the peoples of Siberia. They were attracted by the principles on the basis of which religious or everyday objects were made: idols, spoons, amulets. All this was prepared by a shaman - the spiritual leader of a primitive community. The shaman was a blacksmith, artist, healer, and fortune teller. I wanted to play the same role in society, and not just be a sculptor. There were no translations of Roland Barthes then, but when I later read his “Mythologies” and other articles, I confirmed my intuitions and unformulated thoughts that guided me when doing work in the 1970s.

And even now I am interested in the problem of modern mythology. For me, for example, it is interesting to trace how Russian national symbol- the bear - from a shamanic amulet turned into modern symbol party in power " United Russia" Each Siberian tribe had a bear festival, which ended with the eating of bear meat - the meat of God. The name of God cannot be pronounced, so an animal is described that is in charge of honey. And now a bear has been chosen as the symbol of the largest party. Why not, for example, choose an elephant - a strong, huge, intelligent animal? No, that bear again. And this is in the age of computers, flights to space and the moon, in the age of cloning and all kinds of technical miracles. Belonging to Russian culture pushes me to get to the roots of everything that concerns it.

Leonid Sokov. Bear. 1984. Painted wood, metal. Collection of Ekaterina and Vladimir Semenikhin. Exhibit of the exhibition “Field of Action. Moscow conceptual school and its context. 70-80s of the XX century" at the EKATERINA Cultural Foundation, 2010

B.D.: Doesn’t the distance to Russia make working with Russian archetypes more difficult? Or, on the contrary, is it easier to look at them from afar?

L.S.: In the early 1980s, a group of artists from Moscow emigrated to New York. Each in his own way was busy with the deconstruction of socialist realism. The impossibility of returning to Moscow and being in a different cultural context, the detachment helped to look at socialist realism from the outside. I believe that it was in New York in the early 1980s that the principles of Sots Art were formulated. What these artists did in Moscow was done on an intuitive level. By rearranging accents, using irony, and transferring the heroes of socialist realism to another context, artists from the USSR managed to create a new, fresh movement.

B.D.: When did you first encounter the term “socio art”?

L.S.: I first heard it in New York in the early 1980s. Even in the texts of this time this word is not used anywhere. Margarita Tupitsyna curated an exhibition with this title in the Semaphore gallery in 1984 and in 1986 at the New Museum. Subsequently, the exhibition traveled to museums in the USA and Canada. Attention to social art grew, and gradually this interest transferred to everything modern Russian art. Sots Art is the second original movement in fine art from the USSR and Russia over the past century. It is interesting that the Russian avant-garde of the 1920s appeared at the dawn of the USSR as a pathetic, utopian, abstract movement, and social art - at the end of the Soviet empire as ironic, antipathetic, figurative art.

Leonid Sokov. Stalin and Marilyn. 1989. Mixed media. State Museum fine arts named after A.S. Pushkin. Exhibit of the exhibition “Field of Action. Moscow conceptual school and its context. 70-80s of the XX century" at the EKATERINA Cultural Foundation, 2010

B.D.: How do you feel about attempts to extend the definition of “socio art” to post-Soviet artistic practices?

L.S.: With the disappearance of the USSR, social order, the basis of socialist realism, disappeared, and “classical” socialist art ended due to the disappearance of the context in which it grew and existed. A lot of followers of Sots Art appeared, even in China, but everything done after 1991 looks a lot like a political caricature. Political caricature is also an art, but an applied one, which always has short-lived political content in the foreground. With the disappearance of content, the art illustrating it also becomes irrelevant. Boris Efimov's caricatures of Hitler during World War II were very popular, but in terms of artistic quality they cannot be compared with the brilliant caricatures of Leonardo da Vinci, just as an anecdote cannot be compared with a myth.

Since the early 1990s, I have made a lot of work based on the same principles of the 1970s, but the relevance in Russian culture has shifted from social themes to others. The artist’s task also includes choosing an idea that should be tempting for his contemporary society. I'm interested in tracing how the myth about . When I arrived in New York, few people, even in the art world, knew about such an artist - only certain specialists involved in the Russian avant-garde. And now Malevich has turned from unknown artist into a genius of the twentieth century. In all this time he hasn’t done a single new job. Here is an example of how myth works and what a huge power it is.

The material uses a frame from a video interview with Leonid Sokov, filmed by the Moscow Museum of Modern Art as part of the “Contemporaries” program.

The Tretyakov Gallery on Krymsky Val is hosting a special project by the sculptor and one of the leaders of Sots Art, Leonid Petrovich Sokov (born 1941). The master’s works are dispersed throughout the permanent exhibition “Art of the 20th Century” - from the halls of the early avant-garde to the socialist realism of the 1940s-1950s, introducing the irony of postmodernism into these spaces.

Thus, Sokov acts as a guide, commentator and interpreter of the Tretyakov Gallery collection, pointing out artists close to him, emphasizing the most important works, movements and periods. The special project is the result of the author’s reflections on the artistic searches of the masters of Russian art of the last century and at the same time - self-reflection, an attempt to understand one’s own plastic experience, its origins, specifics and patterns.

During his years of study at the Moscow Secondary Art School and the Moscow Higher Art and Industrial School (formerly Stroganov), Sokov painted a lot at the Moscow Zoo, honing his skills, his ability to “grab” the characteristic features of living nature and generalize what he saw, discarding the unnecessary to achieve the greatest expressiveness. Like many Soviet sculptors, Sokov was influenced by Alexander Matveev, the teacher of his teachers. After graduating from college, Sokov became a member of the Moscow Union of Artists, and then a member of the bureau of the sculpture section. But he was too cramped within the boundaries established for the Soviet artist. He quickly evolved - the budding animal painter was interested in modern Western plastic arts and participated in unofficial exhibitions. A distinctive feature of his works was the ironic play of quotes, symbols and allegories. In 1979, the sculptor emigrated from the USSR.

Now the Tretyakov Gallery houses about 30 works by Sokov. The first, in 1993, the museum received a gift from the author of the work “Stalin with a Bear’s Leg” (1993), in 1996 - “Toucan” and “Serval” (both 1971) from the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation. In the early 2000s, “Portrait of a Bureaucrat” (1984) and “Glasses (Glasses for Every Soviet Person)” (2000, the author’s repetition of a 1976 work) were received, the latter being works from the collection of the Soviet underground by Leonid Talochkin, transferred to the museum in 2014 . In addition to works from the Gallery’s collection, the special project also includes works from the private collections of Dmitry Volkov, Shalva Breus, Ekaterina and Vladimir Semenikhin, Vladimir Antonichuk, Simona and Vyacheslav Sokhransky, which are important for revealing the theme.

As part of a special project, one of Sokov’s most paradoxical objects was placed in the courtyard of the Tretyakov Gallery on Krymsky Val - a life-size reproduction of a truck with Malevich’s suprematist coffin in the back and a “Black Square” on the hood. The truck, made of wood, resembles a giant children's toy, created in the tradition of Russian carved crafts. The combination of interest in the avant-garde and folk tradition, the archaic, and the primitive is the most important feature of Sokov’s creative method.

One of the main heroes of Sots Art, participant in the Venice Biennale and others international exhibitions, sculptor Leonid Sokov(b. 1941) in a special project for the State Tretyakov Gallery " Unforgettable meetings" reveals to the public his favorite artists, showing how his own works- from early animal paintings and female nudes to ironic installations with Soviet leaders. Especially for this project, the museum presents from its storerooms the works of such masters as Vasily Vatagin,Alexander Matveev,Dmitry Tsaplin. And in the courtyard of the building on Krymsky Val, one of Sokov’s objects has been standing since the summer - a car with a Suprematist coffin Malevich.

In 2012, you had a retrospective at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art. What now, what is the idea of your exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery?

When you live outside of Russia - and I’ve been doing this for 36 years, literally half my life I’ve lived in America - you see how a foreign culture does not accept you. People don't understand what you're doing. And in the end, a person who has lived there focuses on Russian culture. But from the very beginning I concluded that I would be interesting everywhere only if I showed what was unique to me through my culture. I conceived the exhibition in the form of dialogues with different visual cultural layers. And this is not an invasion, not an intervention - I cannot stand it. I don't want to fight with anyone. On the contrary, I want to mingle with the people who influenced me. And it turned out very fortunately that the Tretyakov Gallery has a lot of my works, and now more have been added from the collection Leonid Talochkina(collection recently transferred to the State Tretyakov Gallery from the Museum Center of the Russian State University for the Humanities. - TANR).

How many of your works are in the Tretyakov Gallery?

About 30. Once upon a time they bought " Portrait of a Bureaucrat"- This Andropov with moving ears - and « Glasses for every Soviet person". And then Andrey Erofeev(in the early 2000s, head of department the latest trends Tretyakov Gallery — TANR) in a friendly manner lured me out a large number of works, asked me to give them as a gift.

After all, you were initially involved in animal sculpture.

Yes, I made money from this, I was in the Moscow Union of Artists. When I left the USSR in 1979, I was expelled, of course, I was simply thrown out. And then, in modern times, friends who became high-ranking in the Moscow Union of Artists invited me to join it again. I got my ticket back, that's all. And in Soviet time I was a member of the bureau of the sculpture section.

Bureau member? Was this important?

Important. In order to be integrated into this society and make money, just not working as a watchman, that was important. And I all the time, even from the Moscow Art School (Moscow Secondary Art School, now the Moscow Academic Art Lyceum Russian Academy arts — TANR), was an animal painter, and Vasily Vatagin himself praised me as much as he could with his Buddhist philosophy.

I was into cats back then. I was a good draftsman and drew at the zoo all the time while I was studying at the Moscow Art School. From 1956 to 1961. I climbed over the wall because it was expensive to buy a ticket. At that time I was very influenced by French sculpture. Even then I knew who he was Pompon(François Pompon, 1855-1933. — TANR). By the way, he is little known here.

Pompon? I do not know either.

In France they love him. Small castings were common there, for salons, in the fashionable Napoleonic style. Let's say Bari(Antoine-Louis Bari, 1795-1875. - TANR) - remember, panthers, crocodiles? Rodin considered him my teacher, and then he Matisse copied. Pompom influenced, it seems to me, Arpa. Pompom was first a plaster molder for Rodin, and then he became an animal painter, making small sculptures: a pheasant, a duck and - the most famous - a polar bear. They are even sold as souvenirs at the Orsay Museum.

And yet, is your most famous “hero” - the Russian bear - at the exhibition? And in particular, your mobiles with bears, based on the idea of a folk toy?

These mobiles will not be at the exhibition. I came up with the idea of making souvenirs with them; there will be a limited edition of these toys.

The industries have all died. But there is popular consciousness, it also exists in other forms, for example in ditties, most often in obscene ditties. I have a lot of obscenity. I made a monument 2.3 m high out of three famous letters. Of course, you can’t exhibit it in the Tretyakov Gallery, you have a law. I didn't even argue. You can pass a lot of laws, but you cannot prohibit a person from speaking his language.

Does the Tretyakov Gallery provide exhibits from its collection for your exhibition? Works by other artists?

Yes. I will mix my works with Vatagin, I will have a hall, and with Tsaplin. Because I admired these people, I knew them a little. Dmitry Tsaplin (1890-1967. - TANR) little is known, although this is a very interesting sculptor. The Russians know how to do this: they will miss very interesting figures, and then frantically try to save works that have already disappeared somewhere. It's a whole story. When I graduated from Stroganovka, the Matveev school dominated there. Do you know the Matveev school? (Alexander Matveev, 1878-1960. - TANR). I succeeded in this and graduated from college very well. But then, of course, the question arose about being released from school. And I began to make small wax figures; I still have them.

Have the things you used to earn money survived?

I don't know. Then there were two plants, Moscow and regional. You came there, set up a model: I want to sculpt this. They said: well, brilliant! Once - and you sculpted 2 meters, some kind of goat. For children's playgrounds, or placed somewhere in parks.

There are also a lot of deer left. It would be interesting to know who their author is.

I made deer great sculptor Popandopulo(George Popandopulo, 1916-1992. - TANR). If you drive along the Golden Ring, they stand there - proud, like in a parade, only without medals. Once at my plant they wouldn’t accept another goat and they said: “Let Popandopulo decide.” I didn't know who it was then. He called me to his workshop. I came. The workshop is completely empty, only one wall is filled with horns of various animals. A whole wall. He is such a serious Greek-looking man, bald. And the first thing he did was not ask about my aesthetic views, he asked: “Who is this?” I say: “This is teke.”

And who is Teke?

Teke is a type of antelope. Then: “Who is this?” - “This is a Caucasian tour.” - "And who is this?" Conducted an exam on horns. And I answered everything to him, without hesitation. I knew all this by heart then. Well, he was completely stunned: “Let’s go.” He arrived and accepted my sculpture immediately. I realized that I had run into my own. Then, when I graduated from college, I began to sculpt these goats. This is where I was an expert. And there was also an animalist Marz(Andrey Marts, 1924-2002. - TANR). He accepted everything from me, he liked the way I did it. He simply cherished a dream... They all thought that I would be a great successor of animal art. But it was not there!

Yes, your trajectory is somewhat steep.

Director of the Tretyakov Gallery Zelfira Tregulova approved of the idea of mixing my works with Matveev’s sketches and Queen. Boris Danilovich. He also taught “living sculpture” at Vkhutemas. He started out as a cubist. For example, I erected a monument Bakunin. I made the work out of wood, and it was 1924, winter - the next day everything was taken away for firewood.

Thank God my sculptures were found different periods. 50 more pieces female figures I bought it once Norton Dodge. He bought it from me like a vacuum cleaner when I came to America.

Who was your main collector?

Then yes. I made these small sculptures myself from the garth. Garth is such a fusible material. I sculpted it from wax, melted it in a saucepan, and dried the plaster mold on a radiator. It will lie there for two weeks, and then you take this garth (it melts at 100 degrees), pour it in, and that’s it - you have a sculpture in the material.

You have several rooms dedicated to different important milestones, right?

It all starts with the permanent exhibition hall, where Mikhail Larionov And Natalia Goncharova, from the avant-garde. Then Korolev, Vatagin, Tsaplin, mixed with my works. And finally, since I am a social artist, I was allowed to stage “ Lenina and Giacometti"in the socialist realist hall, where Stalin and... all these “unforgettable meetings” (large canvases from the 1950s depicting Stalin’s meetings with the Soviet people. - TANR).

Do you feel comfortable in this room?

I'm not opposing man. For some reason, it is generally accepted that Sots Art is a movement that opposed Soviet reality. In fact, like any postmodernist movement, it was, as it were, a deconstruction of socialist realism, ironic and absurdist. This is called “heroic social art”. Then it seemed that Sots Art were those who opposed it. But in fact, no. Like any postmodernist movement, Sots Art fits well into the trends that existed in Europe at that time. Let's say, transavantgarde, which also relied on the past of art, Italian arte povera, German neo-expressionism. So did the Sots artists, they looked at their past, which is actually very interesting. We are used to saying: look, he sent Stalin. No! The fact is that Stalin was a hero of socialist realism, and I use him as a character, as the most mythological figure of the era of the Soviet Union. There will be an installation at the exhibition, where Stalin speaks in front of a modernist sculpture. The statue of Stalin is given from the storerooms. Back in 1992, I made this installation, where there are small modernist sculptures, such snags, and Stalin speaks in front of them.

Behind Last year Several rather odious exhibitions took place Soviet artists like Alexander Gerasimov. And no irony is felt anymore - everyone has a serious face. This scares many people. Do you think there was something truly valuable for art in that era, in the style of socialist realism?

I believe that socialist realism, whatever it was - a contribution to art or not - still existed. After all, it lasted for almost a century. As a child, I took it quite seriously that Stalin and Voroshilov- great people and great heroes. And I consider myself a person of Soviet-Russian culture. What's bad about it? What to be ashamed of? Socialist realism can be no less interesting than, say, the ideas that Giacometti developed. This was a social order after all, the order of time is a very interesting phenomenon. This is not something a person does under pressure. Mayakovsky Vladimir Vladimirovich, for example, he lived abroad for six months, then came and wrote a poem “ Lenin": "Two in the room. Me and Lenin - a photograph on a white wall.” So is this a bad poem?

You have seen a new exhibition of the latest trends in the Tretyakov Gallery. As an eyewitness and participant in many stories, maybe you are missing something there?

I'm glad that there is more space devoted to some people. For example, highlighted Mikhail Roginsky. Because he was not a party person, as they say now, a person. I knew already in the 1960s that he great artist. The only one who influenced me at all. As an artist. Let's say there are good artists somewhere far away, abroad, and this is a person who lives next to you and does wonderful things. It was inspiring. How he worked! He even made mistakes, and still everything was conscious and serious.

Now many people compare our current Russian time with the era of stagnation. Many artists don't understand what to do. Some feeling of confusion. Could you give advice to the younger generation?

If I were a young man, I doubt I would have left. Russian, with Russian culture. It still has its own language. Language is very important. You just need to delve into your own, in this... And if you react to this situation correctly, everyone will see it. Time selects those who reflect correctly. The most important thing is to catch this smell of the era.

Tsarevo █ Church of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker Tsarevo parish festive service June 05

Revival of the Sergius Church

Annexation of the Crimean Khanate to Russia Abolition of duties and the mint

Church of St. Dmitry the Myrrh-Streaming in the field

Group Bible Reading and Study Time of Voluntary Infirmity