Biography

Vera Mukhina's talent was admired by Maxim Gorky, Louis Aragon, Romain Rolland and even the "father of nations" Joseph Stalin. And she smiled less and less and reluctantly appeared in public. After all, recognition and freedom are not at all the same thing.In the photo, the sculptor Vera Mukhina

Childhood, family

Vera was born in Riga in 1889, in the family of a wealthy merchant Ignatius Mukhin. Mother lost early - after giving birth, she suffered from tuberculosis, from which she did not escape even in the fertile climate of the south of France. Fearing that the children might have a hereditary predisposition to this disease, the father moved his daughters to Feodosia. Here Vera saw the paintings of Aivazovsky and for the first time took up the brushes ...

When Vera was 14, her father died. Having buried the merchant on the shores of the Crimea, the relatives took the orphans to Kursk. Being noble people, they did not spare money for them. They hired a German woman as governess, then a French woman; the girls visited Berlin, Tyrol, Dresden.

In 1911 they were brought to Moscow to look for suitors. Vera did not immediately like this idea of the guardians. All her thoughts were occupied by the fine arts, the world capital of which was Paris, - it was there that she aspired with all her soul. In the meantime, she studied painting in Moscow art studios.

Misfortune helped Mukhina to get what she wanted. In the winter of 1912, while on a sleigh ride, she crashed into a tree. The nose was almost torn off, the girl underwent 9 plastic surgeries. “Well, okay,” Vera said dryly, glancing into the hospital mirror. "People live with more terrible faces." To console the orphan, her relatives sent her to Paris.

Sculpture

In the French capital, Vera realized that her vocation was to be a sculptor. Mukhina's mentor was Bourdel, a student of the legendary Rodin. One comment of the teacher - and she smashed her next job to smithereens. Her idol is Michelangelo, the genius of the Renaissance. If you sculpt, then not worse than him!Paris also gave Vera great love - in the person of the fugitive Social Revolutionary-terrorist Alexander Vertepov. In 1915, the lovers parted: Alexander went to the front to fight on the side of France, and Vera went to Russia to visit her relatives. There she was caught by the news of the death of the groom and the October Revolution.

Oddly enough, a merchant's daughter with a European education took the revolution with understanding. And during the First World War, and during the Civil War, she worked as a nurse. She saved dozens of lives, including her future husband.

Personal life

The young doctor Aleksey Zamkov was dying of typhus. For a whole month Mukhina did not leave the patient's bed. The better the patient became, the worse Vera herself: the girl realized that she had fallen in love again. She did not dare to tell about her feelings - the doctor was too handsome. Everything was decided by chance. In the fall of 1917, a shell hit the hospital. Vera lost consciousness from the explosion, and when she woke up, she saw the frightened face of Zamkov. "If you died, I would die too!" - Alexei blurted out in one breath ...

In the summer of 1918, they got married. The marriage was surprisingly strong. What the spouses did not have to go through: the hungry post-war years, the illness of the son of Vsevolod.

At the age of 4, the boy injured his leg, and tuberculous inflammation began in the wound. All doctors in Moscow refused to operate on the child, considering him hopeless. Then Zamkov operated on his son at home, on the kitchen table. And Vsevolod recovered!

Sculptor's works

In the late 1920s, Mukhina returned to the profession. The first success of the sculptor was a work called "Peasant Woman". Unexpectedly for Vera Ignatievna herself, the "people's goddess of fertility" received a laudatory review from the famous artist Ilya Mashkov and a grand prix at the exhibition "10 Years of October". And after the exhibition in Venice, "Peasant" was bought by one of the museums in Trieste. Today this creation adorns the collection of the Vatican Museum in Rome.

Inspired Vera Ignatievna worked without stopping: "Monument to the Revolution", work on the sculptural decoration of the future hotel "Moscow" ... But everything was useless - each project was mercilessly "hacked to death". And each time with the same wording: "because of the bourgeois origin of the author." My husband is in trouble too. His innovative hormonal drug "Gravidan" annoyed with the effectiveness of all doctors of the Union. Denunciations and searches brought Alexey Andreevich to a heart attack ...

In 1930, the couple decided to flee to Latvia. The idea was thrown up by agent provocateur Akhmed Mutushev, who came to Zamkov under the guise of a patient. In Kharkov, the fugitives were arrested and taken to Moscow. They interrogated them for 3 months, and then they were exiled to Voronezh.

Two geniuses of the era were saved by the third - Maxim Gorky. The same "Gravidan" helped the writer to improve his health. "The country needs this doctor!" - the novelist convinced Stalin. The leader allowed Zamkov to open his institute in Moscow, and his wife to take part in a prestigious competition.

The essence of the competition was simple: to create a monument praising communism. The year 1937 was approaching, and with it the World Exhibition of Science and Technology in Paris. The pavilions of the USSR and the Third Reich were located opposite each other, which complicated the task for the sculptors. The world had to understand that the future belongs to communism, not Nazism.

Mukhina presented the sculpture "Worker and Collective Farm Woman" for the competition, and unexpectedly for everyone she won. Of course, the project had to be finalized. The commission ordered both figures to be dressed (Vera Ignatievna had them naked), and Voroshilov advised "to remove the bags under the eyes from the girl."

Inspired by the era, the sculptor decided to assemble figures from shining sheets of steel. Before Mukhina, only the Eiffel with the Statue of Liberty in the United States dared to do this. "We will surpass him!" - Vera Ignatievna declared confidently.

A steel monument weighing 75 tons was welded in 2 months, dismantled into 65 parts and sent to Paris in 28 cars. The success was colossal! The composition was publicly admired by the artist Frans Maserel, the writers Romain Rolland and Louis Aragon. In Montmartre, inkpots, purses, scarves and powder boxes with the image of the monument were sold, in Spain - postage stamps. Mukhina sincerely hoped that her life in the USSR would change for the better. How wrong she was ...

In Moscow, Vera Ignatievna's Parisian euphoria quickly dissipated. Firstly, her "Worker and Kolkhoz Woman" was badly damaged on delivery to her homeland. Secondly, they installed it on a low pedestal and not at all where Mukhina wanted (the architect saw her creation either on the arrow of the Moskva River, or on the observation deck of Moscow State University).

Thirdly, Gorky died, and the persecution of Alexei Zamkov flared up with renewed vigor. The institute of the doctor was ransacked, and he himself was transferred to the position of an ordinary therapist in an ordinary clinic. All appeals to Stalin had no effect. In 1942, Zamkov died due to the consequences of a second heart attack ...

Once in Mukhina's studio, a call rang from the Kremlin. “Comrade Stalin wishes to have a bust of your work,” the official rapped out. The sculptor replied: “Let Joseph Vissarionovich come to my studio. Sessions from nature are required. " Vera Ignatievna could not even imagine that her businesslike answer would offend the suspicious leader.

From that day on, Mukhina was in disgrace. She continued to receive Stalinist prizes, orders and sit on architectural commissions. But at the same time, she had no right to travel abroad, hold personal exhibitions and even register a house-workshop in Prechistensky Lane as property. Stalin played with the sculptor like a cat with a mouse: he did not finish off completely, but he did not give freedom either.

Death

Vera Ignatievna survived her tormentor for six months - she died on October 6, 1953. The cause of death is angina pectoris. Mukhina's last work was the composition "Peace" for the dome of the Stalingrad planetarium. A majestic woman holds a globe from which a dove takes off. This is not just a will. This is forgiveness."In bronze, marble, wood, the images of people of the heroic epoch were carved with a bold and strong chisel - a single image of man and human, marked by the unique seal of great years "

ANDart critic Arkin

Vera Ignatievna Mukhina was born in Riga on July 1, 1889 in a wealthy family andreceived a good education at home.Her mother was Frenchfather was a gifted amateur artistand Vera inherited her interest in art from him.Her relationship with music did not work out:Verochkait seemed that his father did not like the way she played, and he encouraged his daughter to draw.ChildhoodVera Mukhinapassed in Feodosia, where the family was forced to move because of the serious illness of the mother.When Vera was three years old, her mother died of tuberculosis, and her father took her daughter abroad for a year, to Germany. Upon their return, the family settled again in Feodosia. However, a few years later, my father changed his place of residence again: he moved to Kursk.

Vera Mukhina - Kursk high school student

In 1904, Vera's father died. In 1906 Mukhina graduated from high schooland moved to Moscow.

Haveshe no longer had any doubts that she would be engaged in art.In 1909-1911 Vera was a student of a private studiofamous landscape painterYuona. During these years, he first showed interest in sculpture. In parallel with painting and drawing with Yuon and Dudin,Vera Mukhinavisits the studio of the self-taught sculptor Sinitsyna, located on the Arbat, where, for a reasonable fee, one could get a place to work, a machine tool and clay. At the end of 1911, Mukhin transferred from Yuon to the studio of the painter Mashkov.

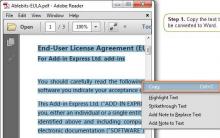

Early 1912 VeraIngatievnashe was staying with relatives on an estate near Smolensk and, while riding a sleigh from the mountain, she crashed and mutilated her nose. Home-grown doctors somehow "sewed" the face on whichfaithI was afraid to look. The uncles sent Vera to Paris for treatment. She steadfastly underwent several face plastic surgeries. But the character ... He became harsh. It is no coincidence that later many colleagues will christen her as a person of "tough disposition". Vera completed her treatment and at the same time studied with the famous sculptor Bourdelle, at the same time attended the La Palette academy, as well as the school of drawing, which was led by the famous teacher Colarossi.

In 1914 Vera Mukhina toured Italy and realized that her real vocation was sculpture. Returning to Russia at the beginning of the First World War, she creates the first significant work - the sculptural group "Pieta", conceived as a variation on the themes of Renaissance sculptures and a requiem for the dead.

The war radically changed the way of life. Vera Ignatievna leaves sculpture classes, enters nursing courses and in 1915-17 works in a hospital. Thereshe also met her betrothed:Alexey Andreevich Zamkov worked as a doctor. Vera Mukhina and Alexey Zamkov met in 1914, and got married only four years later. In 1919, he was threatened with execution for participation in the Petrograd mutiny (1918). But, fortunately, he ended up in the Cheka in the cabinet of Menzhinsky (from 1923 he headed the OGPU), whom he helped to leave Russia in 1907. “Eh, Alexey,” Menzhinsky told him, “you were with us in 1905, then you went to the whites. You can't survive here. "

Subsequently, when Vera Ignatievna was asked what attracted her to her future husband, she answered in detail: “He has a very strong creativity. Internal monumentality. And at the same time a lot from the man. Internal rudeness with great mental subtlety. Besides, he was very handsome. "

Alexey Andreevich Zamkov was indeed a very talented doctor, he treated in an unconventional way, tried folk methods. Unlike his wife Vera Ignatievna, he was a sociable, cheerful, sociable person, but at the same time very responsible, with an increased sense of duty. They say about such husbands: "With him she is like a stone wall."

After the October Revolution, Vera Ignatievna is fond of monumental sculpture and makes several compositions on revolutionary themes: "Revolution" and "Flame of the Revolution". However, her characteristic expressiveness of modeling, combined with the influence of Cubism, was so innovative that few people appreciated these works. Mukhina abruptly changes the field of activity and turns to applied art.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mukhinsky vases

Vera Mukhinais getting closer toI am with the avant-garde artists Popova and Exter. With themMukhinamakes sketches for several productions of Tairov at the Chamber Theater and is engaged in industrial design. Vera Ignatievna designed labelswith Lamanova, book covers, sketches of fabrics and jewelry.At the Paris Exhibition of 1925collection of clothescreated from sketches by Mukhina,was awarded the Grand Prix.

Icarus. 1938

"If now we look back and try once again with cinematic speed to survey and compress the decade of Mukhina's life,- writes P.K. Suzdalev, - past after Paris and Italy, then we will face an unusually difficult and turbulent period of the formation of the personality and creative searches of an outstanding artist of the new era, a woman artist who is emerging in the fire of revolution and labor, in an irrepressible striving forward and painfully overcoming the resistance of the old world. The impetuous movement forward, into the unknown, in spite of the forces of resistance, towards the wind and storm - this is the essence of Mukhina's spiritual life of the past decade, the pathos of her creative nature. "

From drawings-sketches of fantastic fountains ("Woman's figure with a jug") and "fiery" costumes to Benelli's drama "A Dinner of Jokes", from the extreme dynamism of "Archery" she comes to projects of monuments "Liberated Labor" and "Flame of Revolution", where this plastic idea takes on a sculptural existence, a form, albeit not yet fully found and resolved, but figuratively filled.This is how “Yulia” was born - named after the ballerina Podgurskaya, who served as a constant reminder of the shapes and proportions of the female body, because Mukhina greatly rethought and transformed the model. “It was not that heavy,” Mukhina said. The refined grace of the ballerina gave way in "Julia" to the fortress of consciously weighted forms. Under the sculptor's stack and chisel, not just a beautiful woman was born, but the standard of a healthy body, full of energy, harmoniously folded.

Suzdalev: ““ Julia, ”as Mukhina called her statue, is built in a spiral: all spherical volumes - head, chest, abdomen, thighs, calves - everything, growing out of each other, unfolds as it traverses the figure and spins again, giving rise to the sensation solid, filled with living flesh form of a female body. Separate volumes and the entire statue decisively fills the space occupied by it, as if displacing it, elastically pushing the air away from itself “Julia” is not a ballerina, the power of her elastic, consciously weighted forms is characteristic of a woman of physical labor; it is a physically mature body of a worker or a peasant, but for all the severity of the forms in the proportions and movement of a developed figure there is integrity, harmony and female grace. "

In 1930, Mukhina's well-established life broke down sharply: her husband, the famous doctor Zamkov, was arrested on false charges. After the trial, he is sent to Voronezh and Mukhina, along with her ten-year-old son, follows her husband. Only after Gorky's intervention, four years later, she returned to Moscow. Later Mukhina created a sketch of a tombstone for Peshkov.

Portrait of a son. 1934 Alexey Andreevich Zamkov. 1934

Returning to Moscow, Mukhina again began to design Soviet exhibitions abroad. She creates the architectural design of the Soviet pavilion at the World Exhibition in Paris. The famous sculpture "Worker and Collective Farm Woman", which became Mukhina's first monumental project. Mukhina's composition shocked Europe and was recognized as a masterpiece of 20th century art.

IN AND. Mukhina among the sophomore students of Vhutein

From the end of the thirties to the end of his life, Mukhina worked mainly as a sculptor-portraitist. During the war years, she creates a gallery of portraits of warriors-order-bearers, as well as a bust of Academician Alexei Nikolaevich Krylov (1945), which now adorns his tombstone.

Krylov's shoulders and head grow out of a golden block of elm, as if arising from the natural outgrowths of a dumpy tree. In places, the sculptor's chisel slides over the wood chips, emphasizing their shape. There is a free and relaxed transition from the untreated part of the ridge to the smooth plastic lines of the shoulders and the powerful volume of the head. The color of the elm gives a special, lively warmth and solemn decorative effect to the composition. The head of Krylov in this sculpture is clearly associated with images of ancient Russian art, and at the same time it is the head of an intellectual, a scientist. Old age, physical extinction are opposed to the strength of the spirit, the volitional energy of a person who devoted his whole life to the service of thought. His life is almost lived - and he almost completed what he had to do.

Ballerina Marina Semyonova. 1941.

In the semi-figured portrait of Semyonova, the ballerina is depictedin a state of external immobility and internal composurebefore going on stage. In this moment of "entering the image" Mukhina reveals the confidence of the artist, who is in the prime of her wonderful talent - a sense of youth, talent and fullness of feeling.Mukhina refuses to depict the dance movement, believing that the actual portrait task disappears in it.

Partisan. 1942

“We know historical examples, - Mukhina said at an anti-fascist rally. - We know Jeanne d'Arc, we know the mighty Russian partisan Vasilisa Kozhina. We know Nadezhda Durova ... But such a massive, gigantic manifestation of genuine heroism, which we meet among Soviet women on the days of battles against fascism, is significant. Our Soviet woman deliberately goes to I am not only talking about such women and girls-heroes as Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, Elizaveta Chaikina, Anna Shubenok, Alexandra Martynovna Dreiman - a Mozhaisk partisan mother who sacrificed her son and her life to the motherland, I am also talking about thousands of unknown heroines. Isn't it a heroine, for example, any Leningrad housewife who, in the days of the siege of her hometown, gave the last crumb of bread to her husband or brother, or just a male neighbor who made shells? "

After the warVera Ignatievna Mukhinafulfills two large official orders: creates a monument to Gorky in Moscow and a statue of Tchaikovsky. Both of these works are distinguished by the academic nature of their execution and rather indicate that the artist deliberately leaves modern reality.

|

|

|

The project of the monument to P.I. Tchaikovsky. 1945. Left - "Shepherd boy" - high relief to the monument.

Vera Ignatievna fulfilled the dream of her youth. figurinesitting girl, compressed into a lump, amazes with plasticity, melodiousness of lines. Slightly raised knees, crossed legs, extended arms, arched back, lowered head. Smooth sculpture, something subtly echoing with the "white ballet". In glass, it has become even more elegant and musical, acquired completeness.

Seated figurine. Glass. 1947

http://murzim.ru/jenciklopedii/100-velikih-skulpto...479-vera-ignatevna-muhina.html

The only work, apart from The Worker and the Collective Farm Woman, in which Vera Ignatievna managed to embody and bring to the end her figurative, collective-symbolic vision of the world, is the tombstone of her close friend and relative, the great Russian singer Leonid Vitalievich Sobinov. It was originally conceived as a herm depicting the singer in the role of Orpheus. Subsequently, Vera Ignatievna settled on the image of a white swan - not only a symbol of spiritual purity, but more subtly associated with the swan-prince from "Lohengrin" and the "swan song" of the great singer. This work was a success: Sobinov's tombstone is one of the most beautiful monuments of Moscow's Novodevichy cemetery.

Monument to Sobinov at the Moscow Novodevichy cemetery

The bulk of Vera Mukhina's creative discoveries and ideas remained at the stage of sketches, layouts and drawings, replenishing the ranks on the shelves of her workshop and causing (albeit extremely rarely) a stream of bittertheir tears of the impotence of the creator and the woman.

Vera Mukhina. Portrait of the artist Mikhail Nesterov

“He himself chose everything, and the statue, and my pose, and point of view. He himself determined the exact size of the canvas. All by myself"- said Mukhina. Admitted: “I hate it when they see me working. I never allowed myself to be photographed in the workshop. But Mikhail Vasilyevich certainly wanted to write me at work. I couldn't n not to yield to his urgent desire. "

Borey. 1938

Nesterov wrote it while sculpting "Borea": “I worked continuously while he was writing. Of course, I could not start something new, but I was refining it ... as Mikhail Vasilyevich correctly put it, I began to darn ".

Nesterov wrote with pleasure, with pleasure. “Something is coming out,” he reported to S.N. Durylin. The portrait he performed is amazing in the beauty of the compositional solution (Borey, tearing himself off his pedestal, as if flying to the artist), in the nobility of the colors: a dark blue robe, from under it a white blouse; the subtle warmth of its hue argues with the matte pallor of the plaster, which is further enhanced by the bluish-purple reflections of the robe playing on it.

For several years, neAgainst this, Nesterov wrote to Shadra: “She and Shadr are the best and, perhaps, the only true sculptors in our country,” he said. "He is more talented and warmer, she is smarter and more skilled."This is how he tried to show her - smart and skilled. With attentive eyes, as if weighing the figure of Boreas, with concentrated eyebrows, sensitive hands, able to calculate every movement.

Not a work blouse, but neat, even smart clothes - like the bow of a blouse is effectively pinned down with a round red brooch. His shadr is much softer, simpler, more frank. Whether he cares about a suit - he is at work! And yet the portrait went far beyond the framework initially outlined by the master. Nesterov knew this and was glad of it. The portrait does not speak about clever craftsmanship - about creative imagination, curbed by the will; about passion, holding backdriven by reason. About the very essence of the artist's soul.It is interesting to compare this portrait with photographstaken with Mukhina during work. Because, although Vera Ignatievna did not let photographers into the studio, there are such pictures - they were taken by Vsevolod.

Photo 1949 - working on the statuette "Root in the role of Mercutio". Drawn together eyebrows, a transverse fold on the forehead and the same intense focus of gaze as in the portrait of Nesterov. Lips are also slightly interrogative and at the same time resolutely folded.

The same hot force of touching the figure, the passionate desire to pour a living soul into it through the trembling of fingers.

Another message

Vera Ignatievna Mukhina (1889-1953) was born in Riga. Her artistic abilities were discovered early, but she began to work systematically only in Moscow, where she arrived in 1910. She studies at the private school of K.F. Yuona. She makes her first attempt to work on sculpture in the private workshop of Sinitsyna, where novice sculptors worked without a teacher. However, such work does not satisfy Mukhin.

At the end of 1912, Mukhina moved to Paris and entered one of the private academies where Bourdelle taught. Communication with Bourdel, a living example of his art, his subtle artistic intuition, his criticism develop in her a sense of plastic form, but, perhaps, Mukhina studies even more in museums.

Mukhina spent two years in Paris. Then a trip to Italy. Michelangelo's titanic creativity amazes her.

Mukhina's monumentalism is a natural expression of the main properties of her talent. This becomes especially clear when the victorious revolution of 1917 puts forward new tasks of monumental propaganda for sculpture. Mukhina successfully participates in a number of competitions. In 1925-1927 she exhibited a number of works that attracted the attention of the artistic community: "Julia", "Wind", "Female torso". Her "Peasant" is especially successful. A number of portraits created at that time - Professor Kotlyarovsky, Professor Koltsov, Doctor A.A. Zamkov, the bust "Kolkhoz Woman" testifies to Mukhina's great portrait talent.

The best work of the 30s was the Soviet pavilion at the World Exhibition in Paris, crowned with the sculptural work of Vera Ignatievna Mukhina. The Worker and Kolkhoz Woman group was perfectly aligned with the architecture of the pavilion.

When the Mukhinskaya sculptural group "Worker and Collective Farm Woman" was assembled in Paris in 1937 at the World Exhibition, the curious asked who performed this group, who was its creator. And one of our workers, who understood the question asked in a foreign language, answered like this: “Who? Yes, we are the Soviet Union! "

Feat, creativity, joy, love of life - everything is here, in this great creation by Mukhina. As if the epoch itself, the country itself, shaped this titanic symbol - the steel giants who raised the hammer and sickle skyward, and gave this symbol to the sculptor for execution.

When you see this pathos of flying steel, the forms are beautiful and powerful, when you are imbued with the lofty spirit of this creation, your thought is about your country. About your leadership in the current world. About high primacy, measured by all the difficulties, all the victories that were on the way of our people. This work has become truly epic, popular, included in a number of those values that uplift the soul of the people. The artist's thought seemed to have absorbed the thought of millions of people, became the focus of the people's thoughts about themselves, about their time.

Mukhina completed the project of a monument to Gorky in his hometown.

In the first years of the war, the sculptor creates wonderful portraits of B.A. Yusupova, I. L. Khizhnyak. In one of the halls of the Tretyakov Gallery, the bronze colonel Khizhnyak and the bronze colonel Yusupov are standing side by side. They were twinned with the art of Mukhina. The great artist of the Soviet era Vera Mukhina sculpted these heroic portraits.

The most important thing in Mukhina's work was that she knew how to notice in the character of her contemporaries all the best and the new, born of Soviet reality, to find a wonderful ideal in life and, embodying it, to call into the future. Mukhina achieves a tremendous power of typification in his work "Partizanka".

Monumental art cannot be prosaic, ordinary, it is the art of large, high, heroic feelings and a large image. The ideal is always beautiful. Idealization never contradicts reality, since it is the quintessence of all the beautiful that exists in life and what a person aspires to.

The therapist Krasnodar paid to find out the prices for the reception of the therapist Clinician.

Crimson tongues of flame, impenetrable darkness of the underworld, fantastic figures of ugly devils - everything

Despite the presence of the signature, it remains unclear who was the author of the Hermitage banner. There were several

This intimate everyday plot, which does not claim any philosophical or psychological significance,

His mighty realism, alien here to external effects, captures us with a heartfelt

Young, beardless Sebastian, with thick curly hair, naked, covered only by the loins, tied

The ebullient temperament of the great Flemish master made him very freely apply

The real fame of "Venus with a Mirror" began with an exhibition of Spanish painting organized by the Royal Academy

A variety of forms and colors, a lively rhythm, a special major tone and bright decorativeness are inherent in each of these paintings,

However, the Master of Female Half Figures developed his own personality.

He generalized forms, reduced the number of details and trifles in the picture, and strove for clarity of composition. In the image

Clear lines define the contours of bodies, contrasts of light and shadow reveal their plastic

Christ healing the blind is depicted in the center, but not in the foreground, but in the depths

In the "Night Cafe" - a feeling of emptiness of life and disunity of people. It is expressed all the more strongly that faith in life

This is a programmatic work of the artist, he wrote it with great enthusiasm and thought of it as a challenge to the academic

Wide beautiful forehead. Lips tightly closed. A man of action? Undoubtedly. But also a clever girl, with lively curiosity

It depicted a young woman trampling on the dead head of an enemy. Deep in thought, holding

It is impossible to take your eyes off these murals. They have harmony and grace, they have a light conviviality, they

The Last Judgment. The one on which, according to the teaching of the church, is rewarded to all: both the righteous and sinners. Scary, last

The colors that shone in the immortal paintings of Jan van Eyck were unmatched. They shimmered, sparkled,

The sacrament of marriage was somewhat different in the Middle Ages than it is today. Mutual decision to marry

Dmitrevsky began directing dramatic plays and performances of Russian comic operas in 1780 at the Knipper Theater, then all of Pashkevich's operas, melodrama were staged and partially with his participation.

With his works, Bumanz creates an atmosphere of pleasant surprise, bright uniqueness, soft perception. The paintings make you peer into your unconventional world, into their outlines, and their inviting colors, unpretentious and kind.

However, his appearance in Rome, Raphael, undoubtedly, was primarily indebted to himself - his irrepressible passion for improvement, for everything new, for large and large-scale work. The great take-off begins.

In December 1753, experts went to Piacenza. This time the monks gave them the opportunity to examine the painting. In his review, Giovanini will write: undoubtedly Raphael; the state of the painting is more or less bearable,

And Falcone decided to take on the casting of the statue himself. There is no other way out. Falcone cannot but complete his work. He has too much to do with this monument, and he must bring it to the end. Of course, he is not a caster. But if there is no master,

These ten years have greatly helped the artist to find his credo. Over the years, the apprentice carpenter turns into one of the most educated people of his age. He, who not long ago wrote with errors in French,

Her works were born from constant meditation and strong emotional experiences. Unusually emotional by nature, she reacted sharply to all manifestations of life, took joy and sorrow to her heart. She loved

Kochar tried himself in different directions of painting, wishing to find and confirm in art his individual approach to the world and the person in it. These searches were not limited to purely external techniques, they were

Zalkaln is full of ambitious projects and ideas, aspirations to give all the energy, all the creative experience to its people, to make the streets and squares of the city speak the language of art. He dreamed of "palaces of dreams" - the majestic

Nikolay fell in love with this work all his life. And when he grew up, he began to help his father. Metal became obedient to his hands too.

But did the young man think that it was not the top iron crafts, but the bronze masses of trees that would be submissive to his strong

The essence of the creative process for Belashova lies in the release of thought, and this is not an easy task that requires tremendous mental strength. For her, the purpose of art is to bring a person the joy of belonging.

To enter into a duel, into a dispute with a dead nature, with a viscous, heavy mass of clay, which had to be spiritualized, saturated with your excitement, pain, thought and feeling. She did not copy nature, but re-created the world - from clay

At the end of 1912, Mukhina moved to Paris and entered one of the private academies where Bourdelle taught. Communication with Bourdel, a living example of his art, his subtle artistic intuition, his criticism are developed in her

Huge self-discipline and amazing diligence made Matvey Manizer by the age of thirty a three-times educated person with a wide range of interests and an unusually extensive erudition. But the love of sculpture gained

The pre-revolutionary work of Merkurov was closely associated with the development of the so-called "modern" style, with stylization trends. The early works of Merkurov were characterized by static composition, stiffness of movements,

Of all types of art, this diversely gifted person chooses sculpture. This time forever. He wants to be the one who brings stones to life, who creates bronze legends. The great Repin himself, seeing Shadr's drawings, blessed him on this path.

Twenty years of creative work - and three monuments. Even if the sculptor did not create anything but them, his name would still be firmly embedded in the history of art. For all these three monuments are so dissimilar in content, mood, form

Vatagin studied art from time to time, haphazardly. But his real academy was working from life in many zoos - both during travels in his homeland and in distant overseas countries. Dreams come true

Erzya was not accepted into the Stroganov School in Moscow: he was overgrown (he was already twenty-five years old at that time). The director of the Globa school told him: "Come back to the village and bear those like yourself." The young man replied: “No, I will not come back! I will

Still, Sherwood manages to erect his monument. In 1910, according to his project, a monument to Admiral V.O. Makarov was erected in Kronstadt, on Anchor Square, in front of the Naval Cathedral. On a five-meter block of granite rises

Almost all Orsovites took part in the “Exhibition of Artistic Works for the Tenth Anniversary of the October Revolution”. For this exhibition Mukhina made "The Peasant Woman", first in plaster, then - immediately - in bronze. I chose the topic myself: "Since childhood, since I lived on the estate, I had contact, the inner sense of the peasants."

Is it a risk to conclude an agreement on a topic that is still alien to her art? Only once in her works there was an image of a broad-faced smiling woman tied with a scarf, holding a tight head of cabbage - Vera Ignatievna painted her for the cover of the Krasnaya Niva magazine. The artist was warned by many, but she only smiled in response. She did not object to anyone, did not explain anything, but she sculpted her "Krestyanka" without nature - she imagined her to herself to the smallest detail. “I only sculpted my hands from Alexei Andreevich,- she told later. - All Zamkovs have such arms, with short thick muscles. She sculpted her legs from one woman, the size, of course, was exaggerated in order to get this hammering in, inviolability. A face without nature, out of the head. "

Drawings for the "Peasant Woman" statue. 1927 g.

However, maybe the risk was not so great? It is worth taking a closer look at the drawings she made in those years: the slender figures of 1923, gravitating towards the antique standards of beauty, by 1928 become heavy, become full of flesh. And the movements of the figures are so swift and graceful that they seemed almost sliding in the sheets, replaced by motionless turns, the strength of a static position, and internal tension.

Everything in these pictures leads to the "Peasant". And the direct sketches for the sculpture no longer seem unexpected: sketches of a healthy country woman with a tucked skirt, powerful, widely spaced legs, now rested on the sides, now with arms crossed on her chest. The development of the artist's thought is natural and logical. And although the drawings do not yet have that generalization that will appear in the sketch and then in the statue, the type of the heroine being recreated is definite and unchanged.

It was thanks to the clarity and completeness of the plan that Mukhina managed to make both a half-meter sketch and a large, almost two-meter figure over the summer. She worked first in Borisov - in a temporary workshop built in the middle of the vegetable garden, compiled by Alexei Andreevich from two log cabins, then in Moscow, "Very persistently"... Even the guests who constantly visited Zamkov, fellow doctors and students, who rose from the hayloft at dawn, did not interfere: Alexey Andreevich accepted willingly, treated him widely, loved to come to him. In the morning he went fishing with the guests, in the evening he cooked home brew with the youth - it was noisy and merry.

Vera Ignatievna almost did not take part in the fun, she was in a hurry with modeling. However, she did not hide her work, if anyone asked to look, she let her in, and in the middle of July, when it became especially hot, she took the machine out of the workshop into the garden. True, the doctors in sculpture, and even unfinished, were poorly versed. Perhaps most of all they were interested in the fact that Vera Ignatievna sculpts the hands of the "Krestyanka" from the hands of her husband. “Not only brushes,- one of the students of Zamkov will clarify, - whole hands. Even the gesture of "Peasant" - Alexei Andreevich. He always folded his arms like a Roman patrician. "

"The goddess of fertility, Russian Pomona", said Mukhina about the "Peasant". And further: "Black earth"... There is no contradiction here. Not just Pomona - Russian Pomona, a pagan peasant goddess.

This is how it turned out: a little pagan, massive, as if roughly hewn and very earthly. A fabulous Russian woman, the one that "He will stop the galloping horse, enter the burning hut", will endure any suffering. Column legs grow out of the ground (only at the direction of the commission that accepted the sketch, Mukhina put her heroine on the sheaves); above them, the well-knit torso rises heavily and at the same time easily, freely rises. "Such one will give birth while standing and will not grunt",- said Mashkov; mighty shoulders, worthy of completing a lump of back; and above all this an unexpectedly small head, graceful for this powerful body.

Peasant woman. Bronze. 1927 g.

Tretyakov Gallery.

Tucked-up skirt with flowing pleats, slightly beveled at the back; straight, "top hat" shirt; a woman's handkerchief tied, under which a bunch of hair is guessed, parted in the front; hump nose; soft, somewhat sensual lips.

The folds of the shirt and skirt flow to the ground, and - from top to bottom - all forms of the figure become heavier and larger; each muscle fills up, becomes tangible, weighty, and it seems that there is no force capable of moving the "Peasant" from its place. In the words of Mukhina, here "The" visual weight "of the volumes is of particular importance"- one of the main properties of sculpture, a full-bodied, full-blooded sound of the mass in space.

Analyzing "Krestyanka", critics of the late twenties will remember Bourdelle. Yes, he was Mukhina's teacher. And according to the testimony of the wife of Ternovts N.V. Yavorskaya, in the second half of the twenties, interest in French sculpture again flared up in Vera Ignatievna with special force: again and again she returned in conversations to Bourdel and Mayol. After a year in Paris, Mukhina will visit dozens of sculptural workshops and exhibitions, visit the master and, asking him for the keys and a guide, will inspect all his workshops, every thing; will write an article about the artistic life of Paris and will reward Maillol and Bourdel there in full measure, calling them "the first violins in a general plastic concert", "two trunks that give juices to their younger branches." Yes, passing from "Julia" to "Peasant", she seems to be returning from physicality and intoxication with the harmony of Maillol's living body to the severe restraint and thoughtfulness of Bourdelle. And yet - only outwardly. ”In the same common points of contact that can be found among dozens of artists.

As in "Julia" there is no overt sensuality of Maillol, ( "Art is sensuality itself",- said he), and in "Krestyanka" there are completely different creative criteria and categories of thinking than in Bourdelle. No wonder in the same article Mukhina will separate herself from him, stating that "He has a lot of connoisseurs, but there are few pronounced followers, probably his temperament is very individual and cannot be repeated."

An interesting story is Lazar Isaakovich Dubinovsky, who studied with Bourdelle in the last years of the sculptor's life.

“Bourdelle recognized almost all of his former students, he had a good memory. He smiled, sympathetically, coldly spoke two or three phrases. But he gave the keys to the workshops only to those whose works, or at least photographs from them, seemed interesting to him. He said: "Imitators - and most of those who study here in Paris, do not rise above this - nothing needs to be shown." He did not tolerate imitators, and his favorite student, oddly enough, was Giacometti. "Frame sculpture, but what a talent, what independence of feeling and imagination!"Mukhina was not a copycat, and Bourdelle appreciated this. Of course, she studied the art of sculpture under Bourdelle, but this was a school, and creative influence cannot be understood as a slavish assimilation of one artist to another. “The influence of a great poet on other poets is not that his poetry is reflected in them, but that it excites their own powers; so the sunbeam, illuminating the earth, does not impart its power to it, but only excites the power contained in it ",- asserted V.G. Belinsky. Bourdelle's later things did not find a response in Mukhina ( “... did official things. I didn’t like his friezes at the Marseille Opera: it’s not a big style in which he used to work, but a schematic stylization ”).

The Peasant Woman is much more concrete in terms of the time expressed in it than most of Bourdelle's works. He sought to reveal in his heroes the universality of human feelings, called his students to the embodiment of the "universal and eternal." Mukhina's “Peasant Woman” does not pretend to be a timeless generalization, she is only an expression of her era, but this era is expressed in her truly comprehensively: socially, psychologically, and aesthetically. By her appearance, the structure of her head and figure, she is very Russian; in posture, demeanor, self-confidence - a woman of the late twenties, a peasant woman of the Soviet Union, the mistress of her life; as Vera Ignatievna herself said, "A conscientious person, not a slave."

The critics were unanimous in recognizing this. Mukhina's "Peasant Woman" is undoubtedly the best sculptural work at the exhibition. Crafted in a broad, truly monumental manner, this figure gives the image of great emotional strength ... Rough, thick-legged, with a tucked hem, heavily, firmly and stubbornly spreading her legs, she gives the impression of being hewn with wide swings of an ax, but her whole posture is full of impressive dignity and late strength. In this figure, Mukhina managed to give a truly artistic synthesis of the liberated "black earth". When you look at her, one involuntarily thinks: "Yes, she rules the earth herself."- wrote Ignatius Khvoinik.

Mukhina's long-term artistic searches found an outcome in "Krestyanka", her creative doubts were resolved. She herself said that with this sculpture she finally came to the concept of a generalized image as the basis for her art. She was glad that her formal searches were finally over. And although, as for any real artist, the search for a form for her will end only with death, the positive part of this statement is formulated precisely: the artist's main method from now on will be the generalization of concrete, life observations, the desire for a form that is metaphorically capacious, laconic and monumental. The one that A.V. Lunacharsky characterizes as "Very sparingly taken, expressively generalized realistic monumentalism."

I. D. Shadr. Cobblestone is the weapon of the proletariat. 1927 g.

Next to the "Krestyanka" at the "Exhibition of works of art for the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution" were exhibited such compositions, which deservedly entered the golden fund of Soviet art, such as "Cobblestone - the weapon of the proletariat" by I.D. Shadra, "October" by A.T. Matveeva. "Cobblestone - the weapon of the proletariat" became a symbol of the fighting and victorious working class: showing his hero straightening, Shadr, as it were, summed up the results of all three Russian revolutions, told the viewer not only about what was on the barricades of 1905, but also what followed - in 1917. "October" was impeccable in plastic: relying on classical models and techniques, Matveyev managed to get away from the rehash of conventional mythological images. From the courageous figures, from the spiritualized faces of the Red Army man, worker and peasant, there was an air of confidence in the steadfastness of the conquests of the revolution. And yet the "Peasant" stood out even in this magnificent environment. "Cobblestone - the weapon of the proletariat" was awarded the third prize, "October" - the second, "Peasant" - the first.

The bronze tint of the statue was installed in the Tretyakov Gallery, and in 1934 "Peasant Woman" was exhibited at the XIX International Exhibition in Venice and sold to the Museum of Trieste. For the Tretyakov Gallery, a second bronze ebb was made, and the first in 1946, after the end of the Second World War, became the property of the Vatican Museum in Rome. "If I had been predicted in 1914, when I was in this museum, I would never have believed it,"- Vera Ignatievna smiled.

"The peasant woman" brought Mukhina the opportunity to go to Paris for three months. It seemed that the time was running out: it was necessary to go around the workshops and exhibitions, to feel how the French sculptors live, to visit Cologne at the International Book Exhibition (Mukhina participated in its design), to stop by Budapest to visit Maria Ignatievna. And yet Vera Ignatievna shortened this business trip by another month: on August 11, she marked the tenth anniversary of her marriage to Zamkov. A celebration? Guests? No, the day passed as usual, but she did not want to be far from Alexei Andreyevich that day.

They lived together. Everyone who visited their house said that they did not hear in it either a raised voice or an irritated tone. A quarrel or a shout at all was unthinkable. And the point was not that they both had, as Mukhina said, "Flexible character", but in true respect for each other.

Outwardly, they seemed different, very different. She is restrained, dryish, “with the manners of a discerning teacher,” as one of her contemporaries noted. He is noisy, loud, openly emotional. She is always neat, tight, closed; from the expression on her face it is not easy to understand what is in her soul: she is happy - a barely noticeable half-smile, sad or angry - a stern look, slightly drawn eyebrows. He has something on his heart - then on his face: if he laughs, then to the top of his mouth, if he is sad, then like an autumn cloud. With external decency, he considered little, he could go to any reception with the collar unbuttoned.

Even though Vera Ignatievna gave her the lion's share of her time, she tried to do her work unnoticed by those around her, “alone with herself”. Alexey Andreevich loved to "show himself." He invited students to Borisovo on Saturday and Sunday, when peasants came to him, as if on a church holiday, for a reception - carts with horses stood along the entire street. Remembering that the village helped him survive the hungry years of the civil war, Zamkov received peasants free of charge, and the sick were brought from afar.

Vera Ignatievna was not that scrupulous in everything - she was pedantic. After the success of Julia and Vetra, after the fame brought by the Peasant Woman teaching sculpture in Vhutein, she never agreed to teach senior courses: “I myself have no academic education, what will I teach them?” Such doubts were alien to Alexei Andreevich, he trusted his intuition much more than a textbook. “I all inclined him to theory,” said D.A. Arapov, student of Zamkov, later the chief surgeon of the USSR Navy. - Before the operation, I persuade: "Let's read about such cases!" - “Okay, Mitya, let's read it. Let's do it and then read it. "

Whether Zamkov laughed at the zeal of the novice surgeon or actually "thought out a lot on the go", in any case he did not suffer from disbelief in himself and, on the contrary, on occasion was ready to show off his capabilities effectively. Not at all like Mukhina. And yet they had much more in common than different. Differences are in little things, in appearance, demeanor, in what is easy to get used to in a loved one. General - in the fundamental, the main.

And the main thing was the passion with which each of them devoted himself to his work, an interested, creative attitude to the world around him, goodwill towards people.

The papers left after Vera Ignatievna contain letters she received from people whom she did not personally know, letters of gratitude. From the disabled veteran Ivan Kochnev; Blinded and confused, he wrote to her only because on that day there was an article about her in the newspaper, wrote with a request to tell her where to buy a button accordion inexpensively. Vera Ignatievna herself bought and sent him this button accordion. From Flaxerman, also disabled: "After the war, I have been lying in bed for a year already"; money was transferred to him for treatment. From Palangina, - to her son who had tuberculosis, Mukhina bought a ticket to a sanatorium.

There are even more such letters in Zamkov's archive. Long, eloquent - and sometimes illiterate doodles: "I ask you to bother and send me boots, since I have no one else to turn to, I remember you at any time for your efforts to us." And he, in the thirties, one of the most famous doctors in Moscow, fussed, got, bought, sent.

“He didn’t know how to be indifferent to someone else’s misfortune, grief and could stay for hours by the person who needed his help, although he himself was very busy with other things, - told by Galina Serebryakova. - He never treated patients with the same medicine, according to the standard. Zamkov never tired of asking the patient about his feelings, found out the cause of the disease, he could not disdain to go to the kitchen to prepare a dish according to his recipe, which he considered no less effective for treatment than pills and potions ... And Zamkov had another powerful remedy. - he believed that the word is omnipotent. More than once, visiting him during the reception of patients, I listened with a growing sense of respect, how carefully, intelligently, sometimes with good humor, he spoke to patients, dispelled their fear, healed the soul. "His light hand and faithful eye were noted even before the revolution by Aleksinsky and Gagman, who were famous doctors at that time. Subsequently Burdenko will call him "Diagnostician of Zakharyin's class", in his mouth it will sound the highest mark. Zamkov was a diagnostician, surgeon, therapist, urologist, he treated the common cold and such an unexpectedly rare disease as the Pendinskaya ulcer, he knew medicines and folk medicine very well. Wrote a book on pharmacopoeia, according to Arapov, "Amazing"; almost completely finished, it got lost during the Patriotic War.

These years are some of the happiest for Vera Ignatievna. The son is recovering, gradually throws crutches; she sculpts it at the same time as "The Peasant", sculpts in full growth, without posing any problems. The poured little body on strong, yes, already strong legs. All of it is filled with health, strength.

The study is reliably accurate, almost documentary. One foot after an illness is shorter than the other - Vera Ignatievna reproduces it this way. What a disaster! No one will ever notice this, even the boy will not limp.

Life is adjusted, life does not take much time: Aleksandra Andreevna, her sister-in-law, is running the farm, Anastasia Stepanovna Sobolevskaya, an indispensable member of the family, a friend of Mukhina's mother, is looking after Volik. And although the boy is not always happy with her care: "She never allows me anything!" - he complains to his mother, but Vera Ignatievna is calm. She completely trusts Anastasia Stepanovna, she raised both her and Maria, as long as she can remember herself - Anastasia Stepanovna is always there.

She is surrounded by friends. Shadr. Lamanova. The Sobinov family - at the end of the twenties, Mukhina became very close to her second cousin Nina Ivanovna, the singer's wife. I made friends with Leonid Vitalievich - "Wonderful person." I visited each of the operas in which he sang many times, often took her son with her, and Vsevolod called the artistic box “our box”. She kept a funny poem by Sobinov, written by him after the success of "Krestyanka":

Mukhina willingly showed her acquaintances this funny impromptu. Leonid Vitalievich helped Vera Ignatievna to understand music deeper, broader. Before that, despite the fact that she played and sang, she loved only German composers, especially Wagner. Sobinov introduced her to the music of Russia - to Mussorgsky and Tchaikovsky. Her passion for opera will remain with her even after the death of Leonid Vitalievich. Complaining about the hardships that fame brings, he will quite seriously say: "The only thing she gives is premieres."

She also continues her friendship with Ternovts. Since 1919 he worked at the State Museum of New Western Art. Permanent for twenty years, the head of the museum (originally formed from the collections of I.A.Morozov and S.I. A full member of the State Academy of Art Sciences, a member of the State Academic Council for the Scientific and Art Section, an indispensable participant in the organization of Soviet departments at international exhibitions, Ternovets was a true polymath. No wonder he was called "a storehouse of knowledge" - no matter what country they talked about in his presence, he could always give accurate information, name the works of artists and dates, indicate the required bibliography. His immense authority helped him, almost without means, to increase the museum funds: he either made a successful exchange, then he gave the museum a work donated to him personally. It was not easy to compete with him in the knowledge of young Soviet art. Ternovets did not miss a single exhibition, reviewed them, visited the workshops of sculptors, followed the work of each; he wrote the first monographic article about Mukhina (it was published in 1934 in the magazine "Art"), the first book published in 1937 about her.

He visited the Zamkovs regularly, but even more often Vera Ignatievna went to his museum, she loved the atmosphere that reigned in it, businesslike and at the same time friendly. “Nobody looked for external success and recognition in our country,- told the head of the political and educational work of the museum A.P. Altukhova. - The main thing for all of us was the love of art and the desire to bring art closer to the people. Boris Nikolayevich always behaved very modestly, knew how “not to be the boss”, never gave orders or even indicated, did not reprimand anyone, but they worked with him not for fear, but for conscience. "

The desire to bring art closer to the people was always close to Mukhina, and it is not surprising that she looked closely at the work of museum workers: to visiting lectures at factories, where they organized small traveling graphic exhibitions; to a kind of excursion, during which the guides did not try to cover all the halls, but stopped with the audience in front of several paintings and did not begin a lecture - a conversation: by asking what feelings the paintings evoke, they helped to understand their meaning, to appreciate the artistic merits. A cheerful "methodical song", which was sung by the museum workers ( "We will show you three pictures, we will not say anything about them, you yourself will tell us how you will feel there"), Vera Ignatievna knew as well as they did.

After "Krestyanka" she decided to take a break from the big things, took up portraits. This genre attracted artists very much - they worked on portraits as members of the Society of Russian Sculptors and sculptors of the AHRR - the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, the most massive artistic association of the twenties.

Akhrrovites preferred documentary portraits, chose significant people for portraying who played a role in the life of the country, tried to follow nature as much as possible. The Orsovites believed that the portrait of an intimate psychological one should be replaced by portraits that are representative and at the same time generalized, realistically expressive and at the same time symbolic. Bryullov is right a thousand times! they exclaimed. In a portrait, you want to take all the best from a person! And this is the most difficult task for an artist.

Respect for nature, but not an attempt to imitate it - that was the slogan of the Society of Russian Sculptors.

“The physical image of a person does not always correspond to his psychological image, - explained Domogatsky ... - Under the influence of what we learn about his spiritual essence, or what we put into him, his physical image is also transformed in our representation. We exaggerate those features that are characteristic in our minds ... When you approach unfamiliar people without a preconceived opinion, the image (and characteristics) of the face is formed under the influence of the first laconic impressions. They are strong in their freshness, but insufficient, not complicated by a deeper knowledge of the personality. Usually, in this case, the similarity is superficial, and it is shared, like you, who are little familiar with people. After a while, the impression usually changes greatly, and the work, started on the fly, suffers complex alterations, in accordance with the found new characteristic. "Almost everyone in the Society of Russian Sculptors was engaged in portraits. And Domogatsky, and Kepinov, and Zlatovratsky, and Freekh-Khar, and the Andreev brothers, and Sandomirskaya, and Rakhmanov, and Korolev. Mukhina considered Shadra the founder of the Soviet portrait: in 1922, creating emblems for the first Soviet banknotes by order of Goznak, Ivan Dmitrievich sculpted portraits of his fellow countrymen-peasants: Cyprian Avdeev and Perfiliy Kalganov, having managed not only to find a characteristic Russian nature, but also to convey in the images of peasants something new that entered the life and psychology of the people after the revolution; not bonded - by free labor, his heroes are connected to the land.

I. D. Shadr. The Sower (Detail). 1922 g.

Mukhina also liked the portrait of Krasin performed by Shadr, and yet she considered the best portrait painter not to him, but to Sarra Dmitrievna Lebedeva: “She feels acutely, knows how to combine an open-minded attitude to the model with a serious study of it ... There are no simplifications in her portraits, her characters live a complex spiritual life, do not hide from themselves the tragic contradictions of reality, almost all of them are people of great will and high moral purity” ... In addition, Mukhina was impressed by Lebedeva's persistence in her work, her readiness to overcome obstacles: Sarah Dmitrievna always tried to work from nature, she even sculpted a portrait of F.E. Dzerzhinsky, although it was extremely difficult to bring the working machine and clay into his office at the Main Political Directorate.

S. D. Lebedev. Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky. 1925 g.

Vera Ignatievna also sculpts from life. Not intending to compete with Sarah Dmitrievna in the choice of the portrayed (she sculpted Tsyurup, Budyonny), she turns to those people whom she knows well, with whom she constantly meets. Sculpts Andrei Kirillovich Zamkov - the father of Alexei Andreevich, his sister - Alexandra Andreevna, his cousin - Alexander Alexeevich Zamkov. Sculpts his friends - Professor Sergei Alexandrovich Kotlyarevsky, Professor Nikolai Konstantinovich Koltsov - director of the Institute of Experimental Biology, where Alexey Andreevich works.

Portrait of S.A. Kotlyarevsky. 1929 g.

All these portraits are well-designed, most of them are performed by Vera Ignatievna in bronze. In those days it seems to her that bronze is the best material for a portrait: expressively viscous, obeying the barely noticeable pressure of the fingers; able to convey both the strength of the skeleton and the mobile variability of the human face; beautiful in color saturation.

In all the portraits, the resemblance is carefully recreated, in each face its own characteristic is revealed, but this accuracy is somewhat superficial. Mukhina failed to reveal the nature of her characters. Moreover, at times she followed the “path of least resistance”: in Andrei Kirillovich she emphasized her senile goodness, made him look like a saint in canonical Russian frescoes.

And he was by no means a saint, old man of Zamkov. On the contrary, he is spiteful, petty and indefatigable in desires. He was not loved in the family. Partly because of his difficult nature, suspicious, touchy. Partly because, having lived most of the waste in the city and returned to Borisovo to the grown-up children, he remained a stranger to them. While Marfa Osipovna was alive, she smoothed out family troubles, and now everything has come out. Not a day passed without Andrei Kirillovich complaining to one of his sons about the other or demanding money.

Portrait of a grandfather (Andrey Kirillovich Zamkov). 1928 g.

None of this can be read in a portrait. But the beauty of the old man made it possible to speculate that Mukhina was striving to create "Typical head of a peasant" or even "Thinker, prophet". With this look? Distrustful-wary? (However, one study says so: "... in the ancestral head of the castle, everything strong, energetic, Russian is sculpted and emphasized: a powerful open forehead, a gloomy suspicious look ...")

The portrait of Alexandra Andreevna is just as effective in modeling, but not too meaningful. Soft waves of hair, lush knot, gentle yet stately femininity. But what about her as a person? Beauty - yes! But that's all.

These portraits on display, despite the generally benevolent tone of the articles and reviews, did not evoke the same enthusiasm as the "Peasant" was greeted. Critics immediately noted their weakest point. Each of the portraits evoked direct and clear associations: grandfather - with icon painting; Alexandra Zamkova - with Greek antique heads; Kotlyarevsky - with expressionistic sculptural portraits.

Portrait of A.A. Zamkova. 1930 g.

Is it possible to agree with the opinion that, having seen sculptural portraits in Paris in 1928, replenished with a variety of methods, and unable to decide which of these methods is most suitable for her tasks, Mukhina decides to try them all: both the Greeks and Bourdelle , and Despio, and even Hanna Orlova? Unlikely. How can one imagine that a sculptor who has already felt himself an artist, who has received public recognition, voluntarily decides to do and exhibit things that arouse thoughts of imitation? Moreover, after the credo expressed by Mukhina: "It's scary to steal someone else's!" It is more logical to assume that the lack of awareness and vagueness of the creative intention, the leading thread, led to such a result. All works are professional, well done, but none of them carries the grain of the new.

The Kolkhoz Woman Matryona Levina stands out among these portraits. In it, too, there is also the superficial, "attracted"; No wonder, when I looked at Matryona's smile, the smile of Gioconda was so often recalled, and yet it is not so much a direct influence as its shadow.

She is very attractive, this young kolkhoz woman, although not with the clearly victorious beauty of Alexandra Zamkova. There is some kind of elusive pride in her. This woman is of a strong character, with a subtle and poetic perception of the world. And neither prominent cheekbones, nor large ears, nor a tightly fitting headscarf can hide this.

"Collective farm woman Matryona Levina" pleases not only with the skill of execution - with the density and fullness of the sovereign forms, as it were. In this work, as in embryo, it is outlined what will later become an indispensable quality of Mukhina the portraitist: an attraction to monumentalization, austerity of forms, to a demanding psychological characterization.

Collective farmer Matryona Levina. 1928 g.

This sculpture introduces Mukhina into a common channel with other portrait painters of the ORS. Not yet standing out among them, the artist declares her desire to rise to the philosophical understanding of the personality of the portrayed, to the typification of the image.

Life was measured. Summer in Borisov, winter in Moscow. Modeling portraits did not take Vera Ignatievna's entire time away. Distracting from her, she found time to teach, to work at exhibitions.

Mukhina was always happy when she had the opportunity to design an exhibition. I firmly knew: a thing should not only be beautiful in itself, it should be presented, "shown with a face." I recalled with pleasure:

“Together with Akhmetyev I took part in two exhibitions abroad. One of them was a book exhibition in Cologne in 1927, where we made a section of Ukrainian books. When I traveled abroad in 1928, I stopped in Cologne to see how our exhibitions sound ... The downside of all our decorations is our unrestrained desire to say everything without missing anything. A million words ... Foreigners are stingy in the techniques of exposure. The room, the counter, there are five books on the counter, but what books! And with us - perhaps more! The books were well illustrated, but all of this was presented too loudly, too loaded with numbers and so on. "Isn't it a contradiction? In the first case, Mukhina stands up for stinginess, in the second she tries to make sure that what really exists is doubled and tenfold in the eyes of the viewer. No, everything is logical and reasonable: each book should be considered separately, if there are too many of them, none of them will attract attention; a book is a thing that requires silence, solitude. Fur is a different matter. Sables, silver foxes are a luxury, and the more there are, the stronger the feeling of fabulous wealth will affect. And here and there - a strict calculation, the desire for functionality, a constructive solution to the problem.

“In 1930, an artist and I did part of a fur exhibition for Leipzig. Arranged a moving conveyor of foxes. Foxes are found everywhere - from the Pacific Ocean to Belarus. The further to the east, the darker they are, the more to the west, the redder they are. We have arranged them by color. We didn't have so many sables, but we had to make it as if there were a lot of them. We put the furs on strings of silver and gold, and put mirrors in the back. It turned out to be infinitely many sables " .

The gravitation towards constructive thinking is also reflected in her pedagogical activity: in 1926-1927 she taught modeling classes at the Handicraft Art College; in 1927-1930 years - teaches in Vhutein. Chaikov attracts Vera Ignatievna to this work. “I had to talk to her about her sculptures, and I noticed that she is rationalistic in the good sense of the word; she did not rely on a spontaneous, spontaneous feeling, every fold, every line was thought out, logically grounded. Therefore, I had no doubt that she would be a great teacher. "- he said.

Vera Ignatievna did not give lectures, she preferred to teach in person. I searched for a long time, I wanted the students to like the production, I tried to sculpt it without tension, without internal opposition.

I tried to make my explanations as accessible as possible, each of my requirements understandable to everyone.

“When you look straight into the face of your nature, which is closer to you, say, the bridge of the nose or the chin? - she asked the novice sculptor Govorov. - How deep are the eyes? How deep are the ears set from the face? .. One has a wide skull in its upper part and narrowed to the chin, the other has a radish head, narrow at the top and wide at the bottom ... Only after finding this initial portrait volume, make a nose, eyes, ears on it and so on, which in themselves should also be portraits. "

IN AND. Mukhina among the sophomore students of Vhutein

She remembered Bourdelle's teachings about "architecture of volumes" and "completeness of form." Now I passed on this knowledge to students:

“Always start with large volumes (whatever you do) and, once you find them, move on to smaller ones, and then to even smaller ones. Working like this, you will finally get to the surface. Never lick or smooth your surface to keep it smooth; you will get this smooth itself when you gradually emerge from the depths of large forms to the surface, making smaller forms. "I considered the most difficult thing in teaching to be the ability to understand the creative individuality of the student: “It's a terribly difficult job. Exhausts: afterwards you are squeezed out like a lemon peel. I tried to twist myself to the end. They said Mukhina was a good teacher. " She paid a lot of attention to teaching composition. I came up with such tasks in which the students could show not only the acquired knowledge, but also their own taste, understanding of harmony - everything that was included for Vera Ignatievna in the formula “creative individuality”. Asked: to decorate the facade of the house, the staircase of the interior with a sculpture. Smiled: "These classes gave me something myself ..."

In 1930 Vera Ignatievna will part with teaching. He will return to his problems only theoretically - in 1948, when he will speak at the USSR Academy of Arts at a conference on artistic education and training. Will talk about the need to give the student specific knowledge - "Teach him to look in the context of this art", to equip him with technical skill, to acquaint him in detail and comprehensively with the history of art, without hiding or hushing up anything in it. And also that the teacher is obliged to "preserve individuality", to allow the student to develop freely, not to suppress himself, but to help him find his own path.

This program. It is supplemented by individual fragmentary statements. On the compulsory school:

“We, modern sculptors, do not have enough knowledge ... We must know the shape, anatomy, as in the old days we knew the letter“ yat ”, where it was necessary to insert it without thinking.” On the need for creative independence: “Students can be taught the most amazing sculpting recipes, but if a student cannot look, you cannot do anything with him. To be able to see is a lot. If everyone knew how to sculpt, but not look, then all things would be the same. "For Mukhina, a sculptor was like a pianist, a musician. “Imagine a pianist who, with a passion for music, stumbles all the time in his performance, you will get a pretty concert. Or a virtuoso in performance, but more dispassionate than a machine - this is also an unimportant concert. " And here she, in every possible way trying to "see through the student" and "preserve the individuality of the student", taking care to "like nature", teaches from the basics: clear and clear drawing, knowledge of the volumetric form, painstaking and accurate rough work. Teaches which theme can be used in relief, which in round sculpture. Prevents fine detail and illustrativeness.

What did Mukhina demand from the teacher? Something that only a great artist can give.

“If a student has the ability to feel fervently, it is necessary to cultivate it in every possible way; if the fire of feelings burns brightly, you need to support it, if it burns weakly, you need to kindle it so that until the end of life the soul is forever young and passionate, like Michelangelo's, and always wise, stern and seeking, like Leonardo's, so as not to give your spirit to overgrow with a stale crust of well-being and self-complacency. "Will this concern for youth be reflected in the artist-teacher? Only in a good sense: if you don’t wake up the student’s soul - “your own” (not his, your own, you can hardly suspect Mukhina of poor grammar knowledge) “will grow a callous crust”; both souls are bound together.

The sculptor N.G. Zelenskaya, who studied at Vhutein, talked about what an attractive force Vera Ignatievna's class was, despite the fact that it was difficult to study with her: Mukhina never helped to sculpt, did not lay hands on student work, did not try to make it easier to obtain a diploma. Arming with craft techniques ( "Set specially the nature for the arms and legs"), tried to focus the attention of students on the main thing, on how important it is for the sculpture to bear the traces of the author's personality.

Vhutein existed until 1930; then the students by their specialties were assigned to other institutes, and the painters and sculptors were transferred to the Academy of Arts, to Leningrad. Mukhina refused to move with them - she did not want to part with Moscow.

And yet she soon had to leave - to Voronezh. This departure was associated with the work of Alexei Andreevich.

Working at the Institute of Experimental Biology on the problems of rejuvenation and the fight against old age. Zamkov found a drug that increases vitality. I carried out a series of experiments on animals and tried it on myself. Then he risked giving an injection to the hopelessly ill old woman who had not been able to get out of bed for many months. One injection, second, third, the result was favorable.

At first, Zamkov used the drug (he called it gravidan) only to increase general well-being, to stimulate vigor. Gradually began to use it for other diseases; it seemed to him that in many cases the drug was giving positive results.

Panacea? In medical circles, there was talk of quackery. “The issues of using gravidan are simpler than it seems,” objected Zamkov. - Any disease is, in essence, a violation of the hormonal flow of the body's vital processes ... The richness of gravidan in hormones and other active medicinal substances provides it with a powerful regulating effect on the nervous system and endocrine glands. Hence, the restoration of the disturbed balance in the course of life processes, that is, improvement or recovery. "

They didn’t believe him. At the institute, fermentation began, which Vera Ignatievna explained by "human envy." As a result, a feuilleton appeared in the central newspaper, in which Zamkov was called a charlatan. “The article appeared on the 9th of March,- said Mukhina, - on the birthday of Aleksey Andreevich, and hit him on the head with a butt ”.

Within a few weeks, Alexey Andreevich "turned into a bundle of nerves." Yes, and Vera Ignatievna's nerves were not much better: she was always restrained and calm, and ten years later she began to cry, remembering that time: "I cannot speak about this period of my life without excitement."

It all ended with Mukhina and Zamkov leaving Moscow for Voronezh.

Vsevolod was left with the Sobinovs under the supervision of Anastasia Stepanovna - funny and touching children's letters will fly to Voronezh: "They do not give chocolate." Alexey Andreevich and Vera Ignatievna live in Voronezh together, and they do everything themselves: she goes to the market, washes clothes, washes the floors; he - prepares dinner and washes dishes.

The castles did not give up. While working in a polyclinic serving workers of a carriage and locomotive repair plant, he continued to treat patients with his medicine. One, another, a third, a fourth rose to their feet. And again, queues began to line up at the door of his office.

“I came into contact with the management and party organization of the plant,- he said himself. - I said: you have many who are tired and old. I undertake to repair them. I will fix you, and you will fix the locomotives. Send me with notes. I worked especially with those who were ready to get up on disability. A lot of people have gone back to production. "

They returned to Moscow two years later with a shield, and a research institute was soon established, headed by Alexei Andreevich. They settled on the second floor of the former publisher Liksperov's mansion at the Red Gate. But although Vera Ignatievna lived there for almost fifteen years, she could not fall in love with this apartment. Huge halls, columns, paintings on the stairs: the chariots of Sardanapalus - on the second floor Liksperov had ceremonial rooms. Hastily rebuilt, partitioned off, but either because they did it in haste, or poorly thought out the project, it was not possible to erase the "spirit of formality" from the mansion. The only good thing was that now the workshop was together with the apartment.

In this workshop, Mukhina returned to work again. She performed portraits of Vsevolod, Alexei Andreevich, his brother Sergei. Outwardly, this is a continuation of the family portrait gallery, which began before leaving for Voronezh. The choice of characters does not change, but the troubles she has experienced make Vera Ignatievna study people more seriously and more attentively, ponder deeper into their inner essence, their attitude to life and the world.