The beginning of work on The Inspector General dates back to 1835. On October 7 of this year, Gogol wrote to Pushkin: “Do me the mercy, give me a plot; there will be a comedy of five acts, and I swear - much funnier than the devil. Pushkin really gave Gogol a story about an imaginary auditor. It was this plot that Gogol used as the basis of the comedy.

Pushkin told Gogol how the writer Svinin, who had arrived in Bessarabia, was mistaken for a Petersburg official. A similar case happened with Pushkin himself. When he went to collect material about Pugachev and stopped in Nizhny Novgorod, the local governor Buturlin mistook him for a secret inspector and, upon learning that Pushkin was going further to Orenburg, notified the local governor of Perovsky about this with a letter of the following content: “Pushkin came to us recently. Knowing who he was, I treated him kindly, but I must confess that I do not believe that he would go around to get documents about the Pugachev revolt; he must have been secretly instructed to collect information about faults ... I considered it my duty to advise you to be more careful "(1 P. G. Vorobyov, N. V. Gogol's comedy" The Inspector General "in the practice of studying it in high school. book "Study of creativity NV Gogol at school", 1954, p. 62).

In 1836 the first edition of the comedy "The Inspector General" was completed. In the same year, the comedy was staged for the first time on the stages of the capital. “During the rehearsals, Gogol had to exert a lot of effort in order to overcome the adherence of the actors to the established inert theatrical traditions. The actors could not dare to throw off powdered wigs from their heads, French caftans from their shoulders and put on a Russian dress, in a real Siberian coat of the merchant Abdulin or in Osip's well-worn and greasy frock coat.

Gogol was forced to give orders. He ordered to remove luxurious furniture from the mayor's room and replace it with simple ones, add canary cages and a bottle on the window. On Osip, who was dressed in livery with galloons, he himself put on an oily caftan, which he took off from the lamp-maker who worked on the stage "(2. A. G. Gukasova, Comedy" The Inspector General. "In the book" Gogol at School "Collection of articles, APN, 1954, p. 283).

Gogol continued his work on the comedy "The Inspector General" later, until 1842, when he created the final, sixth, edition.

This persistent and painstaking work of Gogol on comedy testifies to the exceptional importance that he attached to it.

He was especially worried about the idea of how the public understood his comedy correctly, and in order to clarify and deepen its meaning, Gogol wrote in 1842 "Theatrical patrol after the presentation of a new comedy" (which contains the ignorant rumors of a motley audience), in 1846 - "Decoupling of the Inspector", in 1847 - "Addition to" Decoupling of the Inspector ".

http://litena.ru/books/item/f00/s00/z0000023/st007.shtml

Answer the questions (write the answers in a notebook):1 ... In what year did N. V. Gogol begin work on the comedy "The Inspector General"?

2 .What was the plot for the creation of the comedy?

Gogol's element is laughter through which he looks at life both in the stories and in the poem Dead Souls, but it is in the dramatic works (The Inspector General, The Marriage, The Players) that the comic nature of Gogol's genius is especially fully revealed. In the best comedy "The Inspector General", the artistic world of Gogol the comedian is presented as original, integral, animated by the author's clear moral position.

Since working on The Inspector General, the writer has pondered a lot about the deep spiritual conditioning of laughter. According to Gogol, the "high" laughter of a true writer has nothing to do with the "low" laughter generated by light impressions, fluent wit, puns or caricatured grimaces. "High" laughter comes "straight from the soul", its source is a dazzling brilliance of the mind, which endows laughter with ethical and pedagogical functions. The meaning of such laughter is ridicule of the "lurking vice" and the maintenance of "sublime feelings."

In the essays that became literary companions of the "Inspector General" ("An excerpt from a letter written by the author after the first presentation of the" Inspector "to one writer", "Theatrical patrol after the presentation of a new comedy", "The denouement of the" Inspector the lack of ideas of comedy, he interpreted his laughter as "high", combining the sharpness of criticism with a high moral task that opened up to the writer and inspired him. Already in "The Inspector General" he wanted to appear before the public not only as a comic writer, but also as a preacher and teacher. The meaning of the comedy is that in it Gogol both laughs and teaches at the same time. In the "Theatrical passing" the playwright emphasized that the only "honest, noble person" in the "Inspector General" is precisely laughter, and clarified: it contains an eternally beating spring of it, which deepens the subject, makes what would have slipped brightly, without the penetrating power of which the trifle and emptiness of life would not frighten a person so much. "

The comedy in a literary work is always based on the fact that the writer selects in life itself the imperfect, low, vicious and contradictory. The writer discovers a "lurking vice" in the discrepancy between the external form and internal content of life phenomena and events, in the characters and behavior of people. Laughter is a writer's reaction to comic contradictions that objectively exist in reality or are created in a literary work. By laughing at social and human failings, the comic writer sets his own standard of values. In the light of his ideals, the imperfection or depravity of those phenomena and people who seem or pretend to appear exemplary, noble or virtuous are revealed. Behind the "high" laughter hides the ideal that allows you to give an accurate assessment of the depicted. In "high" comedy, the "negative" pole must be balanced by the "positive." Negative is associated with laughter, positive - with other types of assessment: indignation, preaching, protection of genuine moral and social values.

In the "accusatory" comedies created by Gogol's predecessors, the presence of a "positive" pole was mandatory. The viewer found him on the stage, the reader - in the text, since among the characters, along with the "negative" characters, there were necessarily "positive" characters. The author's position was reflected in their relationship, in the monologues of the characters, directly expressing the author's point of view, was supported by non-stage characters.

In the most famous Russian comedies - "The Minor" by DI Fonvizin and "Woe from Wit" by AS Griboyedov - there are all the signs of a "high" comedy. The "positive" characters in "Minor" are Starodum, Pravdin and Milon. Chatsky is also a character expressing the author's ideals, despite the fact that he is by no means a "model of perfection." Chatsky's moral position is supported by non-stage characters (Skalozub's brother, Prince Fyodor, nephew of Princess Tugouhovskaya). The presence of "positive" characters clearly indicated to the readers what was proper and what was condemnable. Conflicts in the comedies of Gogol's predecessors arose as a result of clashes between vicious people and those who, according to the authors, could be considered role models - honest, fair, truthful people.

The Inspector General is an innovative work, which differs in many respects from the previous and contemporary comedy of Gogol. The main difference is that in comedy there is no “positive” pole, “positive” characters expressing the author’s ideas about what officials should be like, there are no heroes-resonators, “mouthpieces” of the author’s ideas. The ideals of the writer are expressed by other means. In essence, Gogol, having conceived a work that was supposed to have a direct moral impact on the public, abandoned the forms of expressing the author's position that were traditional for public, "accusatory" comedies.

Spectators and readers cannot find direct author's instructions on what "exemplary" officials should be, there are no hints of the existence of any other moral way of life than the one depicted in the play. We can say that all Gogol's characters are of the same “color”, are created from similar “material”, and are lined up in one chain. The officials depicted in "The Inspector General" represent one social type - they are people who do not correspond to the "important places" they occupy. Moreover, not one of them ever even thought about the question of what an official should be like, how one should perform his duties.

The "greatness" of the "sins endowed by each" is different. Indeed, if we compare, for example, the curious postmaster Shpekin with the obliging and fussy trustee of charitable establishments Strawberry, it is quite obvious that the “sin” of the postmaster is reading other people's letters (“I love to know what is new in the world”) easier than the cynicism of an official who, on duty, must take care of the sick and the elderly, but not only does not show official zeal, but generally lacks signs of philanthropy (“A simple man: if he dies, then he will die anyway; if he recovers, then he will get well "). As Judge Lyapkin-Tyapkin thoughtfully remarked to the governor's words that “there is no person who does not have any sins behind him,” “sins are different to sins. I tell everyone openly that I take bribes, but why bribes? Greyhound puppies. This is a completely different matter. " However, the writer is not interested in the scale of the sins of the district officials. From his point of view, the life of each of them is fraught with a comic contradiction: between what an official should be and who these people really are. The comic "harmony" is achieved by the fact that there is no character in the play who is not even ideal, but simply a "normal" official.

In portraying officials, Gogol uses the method of realistic typification: the general, characteristic of all officials, manifests itself in the individual. The characters in Gogol's comedy have unique, inherent human qualities.

The appearance of the mayor Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky is unique: he is shown as "a very intelligent person in his own way", it is not for nothing that all district officials, with the exception of the "somewhat free-thinking" judge, are attentive to his remarks about disorder in the city. He is observant, accurate in his rude opinions and assessments, cunning and calculating, although he seems simple-minded. The governor is a bribe-taker and embezzler, confident in his right to use administrative power in his personal interests. But, as he remarked, parrying the attack of the judge, “he is firm in the faith” and goes to church every Sunday. The city for him is a family fiefdom, and the colorful policemen Svistunov, Pugovitsyn and Derzhimord do not so much keep order as they play the role of the mayor's servants. Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky, despite his mistake with Khlestakov, is a far-sighted and perceptive person who cleverly uses the peculiarity of the Russian bureaucracy: since there is no official without sin, it means that everyone, whether he is even a governor, even a “metropolitan thing”, can be “bought” or “deceived” ".

Most of the events in the comedy take place in the mayor's house: it is here that it becomes clear who keeps the luminary of the district bureaucracy "under the thumb" - his wife Anna Andreevna and daughter Marya Antonovna. Indeed, many of the "sins" of the mayor are the result of their whims. In addition, it is their frivolous relationship with Khlestakov that enhances the comic of his position, engenders absolutely ridiculous dreams of a general's rank and service in St. Petersburg. In "Notes for Messrs. Actors", which preceded the text of the comedy, Gogol indicated that the mayor began "heavy service with lower ranks." This is an important detail: after all, the "electricity" of the rank not only elevated Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky, but also ruined him, making him a man "with roughly developed inclinations of the soul." Note that this is a comic version of Pushkin's captain Mironov, the straightforward and honest commandant of the Belogorsk fortress ("The Captain's Daughter"). The governor is the complete opposite of Captain Mironov. If in the hero of Pushkin a person is higher than the rank, then in Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky, on the contrary, bureaucratic arrogance kills the human.

There are bright individual features in Lyapkin-Tyapkin and Strawberry. The judge is a county "philosopher" who has "read five or six" books and loves to speculate about the creation of the world. 11 rand, from his words, according to the mayor, "the hair just stands on end" - probably not only because he is a "Volterian", does not believe in God, allows himself to argue with Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky, but also simply because of absurdity and the absurdities of his "philosophizing". As the wise mayor subtly remarked, "well, otherwise a lot of intelligence is worse than it would be at all." The trustee of charitable institutions stands out among other officials with a penchant for phoning and denunciations. Probably not for the first time he did what he did during the “audience” with Khlestakov: violating the mutual responsibility of officials, Strawberry said that the postmaster “does nothing at all”, the judge - “reprehensible behavior”, the superintendent of schools - “worse than the Jacobin ". Strawberry is perhaps a truly terrible person, a werewolf official: he not only starves people in his charitable institutions and does not heal them (“we don’t use expensive medicines”), but also ruins human reputations, interfering with truth with lies and slander ... Luka Lukich Khlopov, the superintendent of schools, is an impenetrably stupid and cowardly person, an example of a learned slave who looks into the mouth of any bosses. “God forbid to serve on the scientific side! - Khlopov complains. "You are afraid of everything: everyone gets in the way, everyone wants to show that he is also an intelligent person."

The individualization of comic characters is one of the basic principles of Gogol the comedian. In each of them he finds a comic, a "hidden vice" worthy of ridicule. However, regardless of their individual qualities, each official is a variant of “general evasion” from true service to the Tsar and the Fatherland, which should be the duty and a matter of honor of a nobleman. At the same time, it must be remembered that the socially typical in the characters of The Inspector General is only a part of their human appearance. Individual flaws become a form of manifestation of universal human vices in every Gogol character. The meaning of the characters depicted is much larger than their social status: they represent not only the district bureaucracy or the Russian bureaucracy, but also “a person in general” with his imperfections, who easily forgets about his duties as a citizen of heavenly and earthly citizenship.

Having created one social type of official (such an official either steals, or takes bribes, or simply does nothing at all), the playwright supplemented it with a moral and psychological typification. In each of the characters there are features of a certain moral and psychological type: in the mayor it is easy to see an imperious hypocrite who firmly knows what his benefits are; in Lyapkin-Tyapkin - a "philosopher" - a brute who loves to demonstrate his learning, but flaunts only his lazy, clumsy mind; in Strawberry - an earpiece and flatterer, covering up his "sins" with other people's "sins"; in the postmaster, "treating" officials with a letter from Khlestakov - a curious person who loves to peep through the keyhole ... And of course, the imaginary "inspector" Ivan Aleksandrovich Khlestakov is the embodiment of thoughtless lies, an easy attitude to life and widespread human weakness - to ascribe to himself other people's affairs and someone else's glory. This is a man-labardan, that is, a mixture of stupidity, nonsense and nonsense, which pretend to be mistaken for intelligence, meaning and order. “I am everywhere, everywhere,” Khlestakov says about himself and is not mistaken: as Gogol remarked, “everyone, at least for a minute, if not for a few minutes, was or is being done by Khlestakov, but, naturally, he doesn’t just want to admit it ... ".

All characters are purely comic characters. Gogol does not portray them as some kind of extraordinary people - he is interested in them in what is found everywhere and in what ordinary, everyday life consists. Many minor characters reinforce the impression that the playwright is portraying quite ordinary people, no taller than "ordinary height." The second spectator at the “Theatrical passing” in response to the remark of the First spectator “... Do such people really exist? And yet they are not exactly villains "- said:" Not at all, they are not villains at all. They are exactly what the proverb says: "Not thin in soul, but just a cheat." The situation itself, caused by the self-deception of officials, is exceptional - it stirred them up, pulled them out of their usual order of life, only by enlarging, in the words of Gogol, "the vulgarity of a vulgar person." Self-deception of officials caused a chain reaction in the city, making both merchants and locksmiths with a non-commissioned officer, offended by the mayor, accomplices of the comic action. A special role in the comedy was played by two characters who are called “city landowners” in the list of characters - the comedy poster - Dobchinsky and Bobchinsky. Each of them is a simple duplication of the other (their images are created according to the principle: two people - one character). They were the first to report the strange young man they saw at the hotel. These insignificant people ("city gossips, damned liars") caused a stir with the imaginary "inspector", purely lucid persons, who led the county bribe-takers and embezzlers to a tragic denouement.

The comedy in "The Inspector General", in contrast to the pre-Golovian comedies, is a consistent, all-embracing comedy. To reveal the comic in the public environment, in the characters of the district officials and landowners, in the imaginary "inspector" Khlestakov — this is the principle of the author of the comedy.

The comic character in "The Inspector General" is revealed in three comedic situations. The first is the situation of fear caused by the received message about the imminent arrival of the inspector from St. Petersburg, the second is the situation of deafness and blindness of officials, who suddenly ceased to understand the meaning of the words pronounced by Khlestakov. They misinterpret them, they don't hear or see the obvious. The third situation is a substitution situation: Khlestakov was mistaken for an auditor, the real auditor was replaced by an imaginary one. All three comedic situations are so closely interrelated that the absence of at least one of them could destroy the comic effect of the play.

The main source of the comic in The Inspector General is fear, which literally paralyzes the district officials, transforming them from powerful tyrants into fussy, ingratiating people, from bribery to giving bribes. It is fear that deprives them of their reason, makes them deaf and blind, of course, not literally, but in a figurative sense. They hear what Khlestakov says, how he lies improbably and every now and then “cheats”, but they do not get the true meaning of what was said: after all, in the opinion of officials, in the mouths of a “significant person” even the most impudent and fantastic lie turns into truth. Instead of shaking with laughter, listening to tales about a watermelon "seven hundred rubles", about "thirty-five thousand couriers alone" galloping through St. Petersburg streets in order to invite Khlestakov to "manage the department", about how "in one evening" he wrote all the works of Baron Brambeus (O. Senkovsky), and the story "The Frigate" Hope "(A.A. Bestuzhev) and even the magazine" Moscow Telegraph "," the governor and others are shaking with fear ", encouraging the intoxicated Khlestakov “To get excited more,” that is to say complete nonsense: “I am everywhere, everywhere. I go to the palace every day. Tomorrow I will be promoted to field marsh now ... ". Even during the first meeting with Khlestakov, the mayor saw, but did not "recognize" in him a complete insignificance. Both fear and the deafness and blindness caused by it became the soil on which the substitution situation arose, which determined the "ghostly" nature of the conflict and the comedy plot of "The Inspector General".

In The Inspector General, Gogol used all the possibilities of the situational comic available to the comedyographer. Three basic comedic situations, each of which can be found in almost any comedy, in Gogol's play convince the reader with the whole "mass" of comic in the rigid conditionality of everything that happens on stage. "... Comedy should be knitted by itself, with all its mass, into one big, common knot," Gogol remarked in the "Theatrical passing".

In "The Inspector General" there are many farcical situations in which the meager mind and inappropriate fussiness of the district officials are shown, as well as the frivolity and carelessness of Khlestakov. These situations are designed for one hundred percent comic effect: they cause laughter, regardless of the meaning of what is happening. For example, frantically giving the last orders before the trip to Khlestakov, the mayor "wants to put on a paper case instead of a hat." In the phenomena XII-XIV of the fourth act, Khlestakov, who had just declared his love to Marya Antonovna and was kneeling in front of her, as soon as she left, expelled by his mother, "throws herself on her knees" and asks for a hand ... from the mayor's wife, and then, suddenly caught Marya Antonovna rushed in and asks "mama" to bless them with Marya Antonovna "constant love". The lightning-fast change of events caused by Khlestakov's unpredictability ends with the transformation of “His Excellency” into a groom.

The comic homogeneity of The Inspector General determines two major features of the work. First, there is no reason to believe that Gogol's laughter is only "exposing", scourging vices. In the "high" laughter, Gogol saw a "cleansing", didactic and preaching function. The meaning of laughter for a writer is richer than criticism, denial or scourging: after all, laughing, he not only showed the vices of people and the imperfection of the Russian bureaucracy, but also took the first, most necessary step towards their deliverance.

Gogol's laughter contains a huge "positive" potential, if only because those at whom Gogol laughs are not humiliated, but, on the contrary, are exalted by his laughter. The comic characters in the writer's portrayal are not at all ugly human mutations. For him, these are, first of all, people, with their shortcomings and vices, "black ones", those who especially need the word of truth. They are blinded by power and impunity, they are used to believing that the life they lead is real life. For Gogol, these are people who are lost, blind, who never knew about their "high" social and human destiny. This is how the main motive of Gogol's laughter in The Inspector General and in the works that followed it, including in Dead Souls, can be explained: "High" earthly and heavenly "citizenship".

Secondly, Gogol's consistent comedy leads to an almost limitless semantic expansion of comedy. It is not individual shortcomings of individual people whose life offends the moral sense of the writer and arouses in him bitterness and anxiety for the desecrated "title" of a person, but the whole system of relations between people. Gogol's “geography” is not limited to a district town lost somewhere in the Russian backwoods. The county town, as the writer himself noted, is a "prefabricated town", a symbol of Russian and general disorder and delusion. The district town, so absurdly deceived in Khlestakov, is a fragment of a huge mirror into which, according to the author, the Russian nobility, Russian people in general, should look at themselves.

Gogol's laughter is a kind of "magnifying glass" with which you can see in people what they themselves and themselves either do not notice, or want to hide. In ordinary life, the "distortion" of a person, camouflaged by a position or rank, is not always obvious. The "mirror" of the comedy shows the true essence of a person, makes visible real-life flaws. The mirror image of life is no worse than life itself, in which people's faces have turned into "crooked faces." This is what the epigraph to "The Inspector General" recalls.

The comedy uses Gogol's favorite technique - synecdoche. Having shown the "visible" part of the world of the Russian bureaucracy, laughing at the unlucky "fathers" of the district town, the writer pointed to a hypothetical whole, that is, to the shortcomings of the entire Russian bureaucracy and universal human vices. The self-deception of the officials of the county town, due to specific reasons, primarily the natural fear of retribution for what they have done, is part of the general self-deception that makes people worship false idols, forgetting about the true values of life.

The artistic effect of Gogol's comedy is determined by the fact that the real world “participates” in its creation - Russian reality, Russian people who have forgotten about their duty to the country, about the importance of the place they occupy, the world shown in the “mirror” of laughter, and the ideal world, created by the height of the author's moral ideal. The author's ideal is expressed not in a head-on collision of “negative” (more precisely, denied) characters with “positive” (ideal, exemplary) characters, but in the entire “mass” of comedy, that is, in its plot, composition, in the variety of meanings contained in each comic character, in each scene of the work.

The originality of the plot and composition of The Inspector General is determined by the nature of the conflict. It is due to the situation of self-deception of officials: they take what they wish for reality. The allegedly recognized, exposed by them official - "incognito" from St. Petersburg - makes them act as if there was a real auditor in front of them. The resulting comic contradiction makes the conflict illusory, non-existent. Indeed, only if Khlestakov were in fact an auditor, the behavior of officials would be quite justified, and the conflict would be a completely ordinary clash of interests of the auditor and the "audited", whose fate entirely depends on their dexterity and ability to "show off" ...

Khlestakov is a mirage that has arisen because “fear has big eyes,” since it is the fear of being caught unawares, not having time to hide the “disorder” in the city, that has led to the emergence of a comic contradiction, an imaginary conflict. However, Khlestakov's appearance is quite concrete, the reader or viewer from the very beginning (second act) is clear about his true essence: he is just a petty Petersburg official who has lost at cards and is therefore stuck in a provincial backwater. Only "extraordinary lightness of thought" helps Khlestakov not to lose heart in absolutely hopeless circumstances, out of habit hoping for "maybe". He is passing through the city, but the officials think that he came just for them. As soon as Gogol replaced the real auditor with an imaginary one, the real conflict also became an imaginary, ghostly conflict.

The originality of the comedy is not so much that Gogol found a completely new plot line, but in the reality of everything that happens. Each of the characters seems to be in their place, conscientiously playing their role. The county town has turned into a kind of stage, on which a completely "natural" play is performed, striking in its credibility. The script and the list of characters are known in advance, the only question is how the “actors” - officials will cope with their “roles” in the future “performance”.

Indeed, one can appreciate the acting skills of each of them. The main character, the real “genius” of the district bureaucratic scene, is the mayor Anton Ivanovich Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky, who in the past three times successfully played his “role” (“he deceived three governors”), the rest of the officials - who is better, who is worse - also cope with the roles , although the mayor sometimes has to prompt them, "prompting", as if recalling the text of the "play". Almost all of the first act looks like a "dress rehearsal" carried out in a hurry. It was immediately followed by an unplanned "show". After the plot of the action - the message of the mayor - a very dynamic exposition follows. It presents not only each of the "fathers" of the city, but also the county town itself, which they consider to be their fiefdom. Officials are convinced of their right to commit lawlessness, take bribes, rob merchants, starve the sick, rob the treasury, and read other people's letters. The fussy Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky, who rushed to the “secret” meeting and alarmed everyone with the message about a strange young man they had found in the hotel, hastened to push the “curtain” open.

The governor and officials try to "throw dust in the eyes" of an imaginary important person and tremble in front of her, sometimes speechless not only out of fear of possible punishment, but also because one should tremble before any bosses (this is determined by the role of the "audited"). They give bribes to Khlestakov when he asks for a "favor", because they should be given in this case, whereas usually they receive bribes. The governor is kind and helpful, but this is just an integral part of his "role" as a caring "father" of the city. In a word, the officials are doing well.

Even Khlestakov easily enters the role of an important person: he meets officials, accepts petitions, and begins, as befits a “significant person”, to “scold” the owners for nothing, making them “shake with fear”. Khlestakov is not able to enjoy power over people, he simply repeats what, probably, he himself experienced more than once in his St. Petersburg department. The unexpected role transforms Khlestakov, elevating him above everyone, makes him an intelligent, powerful and strong-willed person, and the mayor who really possesses these qualities, again in full accordance with his “role”, for a while turns into a “rag”, “icicle” , complete insignificance. The comic metamorphosis is provoked by the "electricity" of the rank. All the characters - both the district officials with real power, and Khlestakov, the "screw" of the St. Petersburg bureaucratic system, seem to be struck by the powerful current generated by the Table of Ranks, which replaced a person with rank. Even an imaginary bureaucratic "magnitude" is capable of bringing in a movement of generally intelligent people, making them obedient puppets.

Readers and viewers of the comedy are well aware that there was a substitution that determined the behavior of officials until the fifth act, before the appearance of postmaster Shpekin with Khlestakov's letter. The participants in the "performance" are unequal, since Khlestakov almost immediately guessed that he was confused with someone. But the role of the "significant person" is so well known to him that he coped with it brilliantly. Officials, shackled by both unfeigned and the “script” fear, do not notice the blatant inconsistencies in the behavior of the alleged auditor.

"The Inspector General" is an unusual comedy, since the meaning of what is happening is not limited to comic situations. Three dramatic plots coexist in the play. One of them - a comedic one - was realized in the second, third, fourth and at the beginning of the fifth act: the sham (Khlestakov) became a magnitude (auditor) in the eyes of officials. The plot of the comedy plot is not in the first, but in the second act - this is the first conversation between the mayor and Khlestakov, where they are both sincere and both are mistaken. Khlestakov, in the words of the observant mayor, is "nondescript, short, it seems that he would have crushed him with a fingernail." However, from the very beginning, the imaginary inspector in the eyes of the frightened "mayor of the local city" turns into a gigantic figure: Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky "shies", listening to Khlestakov's "threats" "stretching out and trembling with all his body." The governor is sincerely mistaken and behaves as one should behave with an auditor, although he sees that he is a nonentity. Khlestakov inspirational “hlestakovs”, assuming the appearance of a “significant person”, but at the same time speaks the real truth (“I am going to the Saratov province, to my own village”). The mayor, contrary to common sense, takes Khlestakov's words for a lie: “Nicely tied a knot! He lies, lies - and will not end anywhere! "

At the end of the fourth act, to the mutual delight of Khlestakov and the officials, who are not yet aware of their deception, the imaginary "inspector" is carried away from the city by the fastest troika, but his shadow remains in the fifth act. The mayor himself begins to "whistle", dreaming of a Petersburg career. It seems to him that he received "what a rich prize" - "what a devil they have become related to!" With the help of his future son-in-law, Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky hopes to "get a big rank, because he is a fellow with all the ministers and goes to the palace." The comic contradiction at the beginning of the fifth act becomes especially acute.

The culmination of the comedy plot is the scene of the mayor's triumph, who behaves as if he has already received the rank of general. He became above all, ascended above the district bureaucratic brethren. And the higher he ascends in his dreams, taking wishful thinking, the more painful it is for him to fall when the postmaster “in a hurry” brings a printed letter - Khlestakov, a writer, a scribe appears on the stage, and the mayor hates the scribe: for him they are worse than the devil ... It is the position of the mayor that is especially comical, but it also has a tragic connotation. The unlucky hero of the comedy himself considers what happened as a punishment from God: "Behold, truly, if God wants to punish, then he will take away the mind first." Add to this: and will deprive the irony and hearing.

In Khlestakov's letter, everyone discovers even more "unpleasant news" than in the letter of Andrei Ivanovich Chmykhov, read by the mayor at the beginning of the play: the auditor turned out to be an imaginary one, "a helper," "an icicle," a "rag." Reading a letter is the denouement of a comedy. Everything fell into place - the deceived side both laughs and is indignant, fearing publicity and, what is especially offensive, laughter: after all, as the mayor remarked, now “if you go into a laughing stock, there will be a clicker, a scribbler, and will insert you into a comedy. That's what's insulting! He will not spare the rank, he will not spare, and they will all bite their teeth and beat their hands. " The governor is not saddened by his human humiliation most of all, but is outraged by the possible insult of his "rank, title". There is a bitter comic connotation in his indignation: a person who has soiled a rank and title attacks the "clickers", "paper machine", identifying himself with the rank and therefore considering it closed to criticism.

Laughter in the fifth act becomes universal: after all, every official wants to laugh at the others, recognizing the accuracy of Khlestakov's assessments. Laughing at each other, savoring the jabs and slaps that the exposed "inspector" gives in the letter, the officials laugh at themselves. The stage laughs - the audience laughs. The famous remark of the mayor - “What are you laughing at? “You’re laughing at yourself! .. Oh, you! ..” - addressed both to those present on the stage and to the audience. Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky alone does not laugh: he is the most affected person in this whole story. It seems that with the reading of the letter and the clarification of the truth, the circle has closed, the comedy plot has been exhausted. But the whole first act is not yet a comedy, although there are many comic incongruities in the behavior and words of the participants in the meeting with the governor, in the appearance of Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky, and in the hurried gatherings of the governor.

Two other plots - dramatic and tragic - are outlined, but not fully realized. The first words of the mayor: “I invited you, gentlemen, in order to inform you of the unpleasant news: an inspector is coming to us”, supplemented by clarifications that this inspector is coming from Petersburg (and not from the province), incognito (secretly, without publicity), “ and also with a secret prescription ”, caused a serious commotion. The task facing the uyezd officials is quite serious, but feasible: "take precautions", how to prepare for a meeting with the formidable "incognito": cover up, patch up something in the city - maybe it will. The plot of the action is dramatic, vital: a terrible auditor will not fall like snow on his head, the ritual of receiving an auditor and cheating him could be realized. There is no auditor in the first act yet, but there is a tie: the officials woke up from hibernation, fuss. There is not even a hint of a possible substitution, only the fear that they might not be in time worries the officials, first of all the mayor: "You just expect that the door will open and go ..."

So, in the first act, the outlines of a future drama are outlined, in which a favorable outcome of the audit could depend only on officials. The governor's message about the letter he received and the possible arrival of the inspector is the basis for a dramatic conflict, which is quite common in any situation associated with the sudden arrival of the authorities. From the second act to the end of the play, a comedy plot unfolds. In the comedy, as in a mirror, the real world of the bureaucratic bureaucracy is reflected. In laughter, this world, shown from the inside out, revealed its usual features: falsehood, ostentatiousness, hypocrisy, flattery and the omnipotence of rank. Hurrying to the hotel, where the unknown visitor from St. Petersburg was staying, the mayor hurried into the comedy "behind the mirror", into the world of false, but completely plausible ranks and relations between people.

If the action in The Inspector General ended with the reading of Khlestakov's letter, Gogol would definitely have realized the “idea” of the work, suggested to him by Pushkin. But the writer went further, ending the play with "The Last Appearance" and "Dumb Scene": the finale of "The Inspector General" brought the heroes out of the "through the looking glass", in which laughter reigned, reminding them that their self-deception did not allow them to "take precaution", dulled their vigilance ... In the finale, a third plot is planned - a tragic one. The suddenly appeared gendarme informs about the arrival of not an imaginary, but a real inspector, terrible for officials not by his "incognito", but by the clarity of the task set before him by the tsar himself. Every word of the gendarme is like a blow of fate, this is a prophecy about the imminent retribution of officials - both for sins and for carelessness: “An official who came by personal order from St. Petersburg demands you to come to him right now. He is staying at a hotel. " The mayor's fears, expressed in the first act, have come true: “That would be nothing, damn incognito! Suddenly he will look: “Ah, you are here, darlings! And who, say, is the judge here? - "Lyapkin-Tyapkin". - “And bring Lyapkin-Tyapkin here! And who is the trustee of charitable institutions? " - "Strawberry". - "And serve Strawberries here!" That's what's bad! " The appearance of the gendarme is the imposition of a new action, the beginning of the tragedy, which the author took out of the stage. A new, serious "play", in which everyone will not be laughing, should, according to Gogol, not be played in the theater, but happen in life itself.

Its three plots begin with messages: a dramatic one with a message from the mayor, a comic one with a message from Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky, and a tragic one with a message from a gendarme. But only the comic ghost plot is fully developed. In a dramatic plot that remained unrealized, Gogol discovered comic potential, demonstrating not only the absurdity of the behavior of fooled officials, but also the absurdity of the action itself, in which the roles are pre-planned: both the auditor and the audited diligently throw dust in each other's eyes. The possibility of realizing the author's ideal is outlined in the comedy finale: the last and most important emphasis is made by Gogol on the inevitability of punishment.

The play ends with a scene of "petrification". This is a sudden stop of the action, which from that moment could turn from a comedy ending with Khlestakov's exposure into a tragic one. It all happened suddenly, suddenly. The worst happened: no longer a hypothetical, but a real danger loomed over the officials. “Silent Scene” is a moment of truth for officials. They are made "petrified" by a terrible guess about imminent retribution. Gogol the moralist asserts in the finale of The Inspector General the idea of the inevitability of a trial against bribe-takers and embezzlers who have forgotten about their official and human duty. This judgment, according to the writer's conviction, should be done by personal command, that is, by the will of the king himself.

In the finale of the comedy "The Minor" by DI Fovizin, Starodum says, pointing to Mitrofanushka: "Here they are, worthy fruits of malice!" There is no one in Gogol's comedy who even remotely resembled Starodum. The "silent scene" is the author's own finger, this is the "moral" of the play, expressed not by the words of the "positive" hero, but by the means of composition. The gendarme is a messenger from that ideal world created by Gogol's imagination. In this world, the monarch not only punishes, but also corrects his subjects, wants not only to teach them a lesson, but also to teach them. The pointing finger of Gogol the moralist is also turned towards the emperor; it was not for nothing that Nicholas I noticed, leaving the box after the performance on April 19, 1836: “Well, a play! Everyone got it, but I got it more than everyone else! " Gogol did not flatter the emperor. Having directly indicated where the retribution should come from, the writer, in essence, “bored” him, confident in his right to preach, teach and instruct, including the king himself. Already in 1835, when the first edition of the comedy was being created, Gogol was firmly convinced that his laugh was a laugh inspired by a high moral ideal, and not the laugh of a scoffer or an indifferent critic of social and human vices.

Gogol's faith in the triumph of justice, in the moral effect of his play can be assessed as a kind of social and moral utopia generated by his educational illusions. But if there were no such illusions, there would be no “Inspector General”. In it, the comic and laughter were in the foreground, but behind them is Gogol's belief that evil is punishable, and the punishment itself is carried out in the name of freeing people from the ghostly power of the rank, from the "bestial", in the name of their spiritual enlightenment. “Having seen his shortcomings and errors, a person suddenly becomes higher than himself, - the writer emphasized. "There is no evil that cannot be corrected, but you need to see what exactly evil consists in." The visit of the auditor is not at all a "routine" event. The auditor is important not as a specific character, but as a symbol. It is, as it were, the hand of an autocrat, just and merciless to lawlessness, reaching out to the provincial backwaters.

In The Denouement of The Inspector General, written in 1846, Gogol emphasized the possibility of a broader interpretation of the comedy's finale. The inspector is “our awakened conscience” sent “by the Named Supreme Command”, by the will of God, reminding a person of his “high heavenly citizenship”: “Whatever you say, but the inspector who is waiting for us at the door of the coffin is terrible. As if you don't know who this auditor is? What to pretend? This inspector is our awakened conscience, which will make us suddenly and at once look with all our eyes at ourselves. Nothing will hide before this auditor. ... Suddenly, before you, in you, such a monster will open up that a hair will rise from horror. " Of course, this interpretation is only one of the possible interpretations of the symbolically ambiguous ending of the comedy, which, according to the author's plan, should affect both the mind and the soul of viewers and readers.

"Comedy" The Inspector General. History of creation ".

Lesson objectives:

· To acquaint children with the history of the creation of comedy, to develop students' perception of a literary work.

· Give basic theoretical concepts. Explain the nature of Gogol's laughter, instill interest in the writer's works.

During the classes.

Teacher's word.

We ask for Russian! Give us yours!

What are the French and all the overseas people to us!

Do we have little of our people?

Russian characters? Your characters!

Let's ourselves! Give us our rogues ...

On stage! Let all the people see them!

Let them laugh!

Gogol is one of the most read by the school curriculum of writers. In this capacity, he can even compete with Pushkin. Gogol at school is our everything, solid and reliable. For all grades - from 5th to 10th. In all forms - epic, drama and even lyrics. Methodical literature - do not reread (there are even several books with the same title "Gogol in School").

With all this, Gogol is one of the most unread writers in the school. And here, too, is Pushkin's fate: the soul is “in the cherished lyre,” “für Wenige,” and the crowd continues to trail its senseless path to the idol monument. Isn't it about this school-scale monument that Alexander Kushner is talking about:

To be a classic is to stand on a wardrobe

A senseless bust, clavicle bristling.

Oh, Gogol, is this all in a dream, in reality?

So they put a scarecrow: a snipe, an owl.

You stand instead of a bird.

He wrapped himself in a scarf, he loved to tinker

Vests, camisoles.

Not like undressing - swallowing a piece

Couldn't be in front of witnesses - the sculptor was naked

Delivered. Is it nice to be a classic?

Be a classic - watch from the closet in the classroom

For schoolchildren; they will remember Gogol

Not a wanderer, not a righteous man, not even a fancy one,

Not Gogol, but Gogol's top third.

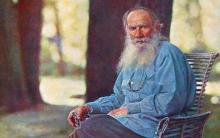

A word about life and creativity.

- years of life.

After graduating from high school - Petersburg, worked as a history teacher, clerical officer. Acquaintance with writers and artists. Since 1831 the name of Gogol is widely known to the Russian reader - the collection “Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka” has been published.

In 1848. after a pilgrimage to the Holy Land to the Holy Sepulcher (Jerusalem), Gogol returns to his homeland. Most of the time he lives in Moscow, visits St. Petersburg, Odessa, Ukraine. In February, in the house on Nikitsky Boulevard, where he lived with the count, in a state of deep mental crisis, the writer burns a new edition of the second volume of Dead Souls. A few days later, on February 21, he died. The writer's funeral took place with a huge crowd of people at the cemetery of St. Danilov Monastery (in 1931, Gogol's remains were reburied at the Novodevichy Cemetery).

Comedy "The Inspector General".

It was 1835. Gogol in St. Petersburg, a city of theaters. Having met with Pushkin, the writer asked: "Do grace, give some funny or unfunny, but purely Russian anecdote ... Do mercy, give a plot, the spirit will be a comedy of five acts, and I swear it will be funnier than the devil." And the poet told him how in Nizhny Novgorod he was mistaken for an auditor; told about how one of his acquaintances presented himself in Bessarabia (Moldavia) as an important St. Petersburg official. The anecdote about the alleged auditor attracted Gogol so much that he immediately got the idea of writing The Auditor, and the comedy was written surprisingly quickly, in two months, by the end of 1835. The person was not taken for who he really is, the person “insignificant” appeared as “significant”. There is confusion behind all this. But error, confusion is the soul of comedy, a constant source of the funny.

The play was first staged on April 19, 1836. at the St. Petersburg Alexandrinsky Theater, and on May 25 - at the Moscow Maly Theater.

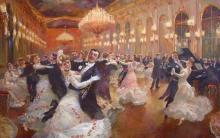

On the evening of April 19, 1836, extraordinary excitement reigned in the theater square. Carriages drove up, carriage doors slammed. Lodges and armchairs were filled with the highest Petersburg nobility, dignitaries. In the royal box - Nicholas I with the heir, the future Alexander II. The gallery is crowded with spectators of the democratic circle. There are many acquaintances of Gogol in the theater - V, Zhukovsky, B. Vyazemsky, I. Krylov, M. Glinka and others. Here is what Annenkov tells about this first performance of the “Inspector General”: “After the first act, bewilderment was written on all faces. Perplexity grows with every act. Everything that happened on the stage passionately captured the hearts of the audience. The general indignation was completed by the fifth act ”.

The tsar laughed a lot at the performance, apparently wanting to emphasize that the comedy is harmless and should not be taken seriously. He understood perfectly well that his anger would be another confirmation of the veracity of Gogol's satire. Publicly expressing the royal complacency, he wanted to weaken the public sound of the "Inspector General". However, being left alone with his retinue, the king could not resist and said: “What a piece! Everyone got it, but I got it more than anyone. "

Plot Comedies were presented to Gogol by Pushkin. A widespread anecdote about an imaginary auditor allowed the author of the play to reveal the customs of officials of Nikolaev's time: embezzlement, bribery, ignorance and arbitrariness. Officialdom became power. Feathers creaked all over the country, uniforms were rubbed, and mountains of papers swelled. And behind all this Russia lived, suffered, sang and cried.

genre Comedy was conceived by Gogol as a genre of public comedy, touching upon the most fundamental questions of people's, social life. Pushkin's anecdote from this point of view was very suitable for Gogol. After all, the protagonists of the story about the alleged auditor are not private people, but officials, representatives of the authorities. The events associated with them inevitably capture many people: both those in power and those under control. The anecdote told by Pushkin easily succumbed to such artistic development, in which it became the basis of a truly social comedy.

Gogol wrote in The Author's Confession: “In The Inspector General, I decided to put together everything that was bad in Russia that I knew then, all the injustices that are done in those places and in those cases where justice is most required of a person. and laugh at everything at once. "

So the comedy was staged. But a few true connoisseurs - educated and honest people - were delighted. Most did not understand comedy and reacted to it with hostility.

“Everyone is against me…” Gogol complained in a letter to the famous actor Shchepkin. "The police are against me, the merchants are against me, the writers are against me." A few days later, in a letter to the historian, he notes with bitterness: “And what the enlightened people would accept with loud laughter and sympathy, the very same outrages the bile of ignorance; and this ignorance is universal ... "

After the performance of The Inspector General on stage, Gogol is full of dark thoughts. He was not satisfied with the acting in everything. He is depressed by the general misunderstanding. In these circumstances it is difficult for him to write, it is difficult for him to live. He decides to go abroad, to Italy. Reporting this to Pogodin. He writes with pain: “A modern writer, a comic writer, a writer of morals must be far from his homeland. There is no glory for the prophet in the homeland. ” But as soon as he leaves the borders of his homeland, the thought of her, great love for her with renewed vigor and acuteness arises in him: “Now there is a foreign land in front of me, a foreign land around me, but Russia is in my heart, not an ugly Russia, but only beautiful Russia ”.

Literary commentary.

In order to understand the work "The Inspector General", we will talk with you about what are the features of a literary work intended for the theater, for staging on stage (this work is called a play).

Features of a literary work intended for theater, for staging on stage: (plays)

- Drama(play) is a literary genus. Drama genres: tragedy, comedy and drama. Comedy- a kind of drama in which the action and characters are interpreted in the forms of the funny or imbued with the comic. Collision- a clash of opposing views, aspirations, interests. Remarks- explanations for stage directors and actors.

They tell you which characters are involved in the play, what they are in terms of age, appearance, position (author's remarks are called posters), the place of action is indicated (room in the house, city, nothing), it is indicated what the hero of the play is doing and how he pronounces the words of the role (“looking back”, “to the side”).

The play is divided into parts - actions or acts. Inside the action there can be pictures or scenes. Each arrival or departure of a character gives rise to a new phenomenon.

2. In the play, the speech of the characters and their actions are recreated in a dialogical and monological form.

In terms of its volume, the play cannot be large, since it is designed for stage performance (2-4 hours). Therefore, in the plays, events develop rapidly, energetically, colliding the characters leading the struggle, latent or explicit - conflict.

The composition of the piece.

3. The action in the play develops through the following steps:

Exposition- the action of the play, drawing the characters and positions of the characters before the start of the action.

Tie- the event from which the active development of the action begins.

Climax- the moment of the highest tension in the piece.

Interchange- an event that completes an action.

Hanger "href =" / text / category / veshalka / "rel =" bookmark "> hangers Gogol knew: a theater begins with a poster.

Gogol said that “if we want to understand dramatic works and its creator, we must enter into his field, get to know the characters” ...

Let's open the program and, carefully familiarizing ourselves with the characters of the comedy, we will try to guess by the last name about the character of the hero.

|

|

Anna Andreevna | His wife |

without a name and patronymic. |

|

Ammos Fedorovich Lyapkin-Tyapkin | Judge. |

Artemy Filippovich Strawberry |

|

Postmaster. |

|

Peter Ivanovich Bobchinsky | Urban |

Ivan Alekseevich Khlestakov | |

Christian Ivanovich Gibner | County doctor. |

Private bailiff. |

|

Svistunov | Police officers. |

What did you think about when you got acquainted with the names of the characters?

Demonstration of a creative task: “At the playbill”.

· Make a poster for the play.

· Make a program for the performance.

Draw illustrations for the play (of any character)

Parade of heroes

Governor.

The mayor, who has already grown old in the service and is not very stupid in his own way. Although he is a bribe-taker, he behaves very respectably; rather serious, somewhat even reasonable; speaks neither loudly nor softly, neither more nor less. His every word is significant. His facial features are coarse and tough, like anyone who has begun a heavy service from the lowest ranks. The transition from fear to joy, from baseness to arrogance is quite quick, as in a person with roughly developed inclinations of the soul. He is dressed, as usual, in his uniform with buttonholes and boots with spurs. His hair is cut with gray.

Anna Andreevna and Marya Antonovna.

Anna Andreevna, his wife, a provincial coquette, not quite old yet, brought up half on novels and albums, half on the hassle of her pantry and girl's. Very curious and shows vanity on occasion. Sometimes he takes power over her husband just because he is not able to answer her; but this power extends only to trifles and consists in reprimands and ridicule. She changes into different dresses 4 times during the play.

Marya Antonovna- daughter of Anton Antonovich Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky (Governor)

Khlestakov.

Khlestakov, a young man of 23 years old, thin, thin; somewhat silly and, as they say, without a king in his head - one of those people who are called empty in the offices. Speaks and acts without consideration. He is unable to stop constant attention on any thought. His speech is abrupt, and the words fly out of his mouth completely unexpectedly. The more the person fulfilling this role shows sincerity and simplicity, the more he will benefit. Dressed in fashion.

Osip.

Osip, the servant, is the way servants of several elderly years usually are. He speaks seriously, looks somewhat downward, is reasonable and loves to read lectures for his master himself. His voice is always almost even, in conversation with the master takes on a stern, abrupt and somewhat even rude expression. He is smarter than his master, and therefore more likely to guess, but does not like to talk much, and silently is a rogue. His suit is a gray or blue shabby coat.

Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky,

both are short, short, very curious; are extremely similar to each other; both have small bellies, both speak quickly and help tremendously with gestures and hands. Dobchinsky is a little taller and more serious than Bobchinsky, but Bobchinsky is more cheeky and lively than Dobchinsky.

Lyapkin-Tyapkin,

a judge, a person who has read five or six books, and therefore somewhat free-thinking. The hunter is big on guesswork, and therefore gives weight to every word. The person who represents it must always keep it. He speaks in a bass, with an elongated stretch, wheezing and glanders, like an old clock that first hiss and then chimes.

Strawberry,

the trustee of charitable institutions, a very fat, clumsy and awkward person, but with all that a sneak and a rogue. Very helpful and fussy.

Laughter is the only "honest, noble face in comedy"

In his article “The Petersburg Scene in 1835-36,” the brilliant satirist said that when creating his comedy, he set himself the goal of “noticing” the common elements of our society, driving its springs. To depict on the stage “chaff” from which life is not good and for which no law is able to follow ”.

Epigraph: “There is no reason to blame the mirror, if the face is crooked” characterizes the genre of comedy - a socio-political comedy.

“The exposure of negative characters is given in the comedy not through a noble person, but through action, deeds, dialogues of themselves. Negative heroes of Gogol themselves expose themselves in the eyes of the viewer ”.

But ... heroes are exposed not through morality and morality, but through ridicule. “Only laughter is striking here vice” (Gogol).

Homework announcement.

https://pandia.ru/text/77/499/images/image004_10.png "alt =" (! LANG: C: \ Documents" align="left" width="50" height="79 src=">5. “Человек “пожилых лет”, смотрит вниз, в разговоре с барином принимает грубое выражение”!}

THE CLEVEREST

1. Poltava is located 1430 versts from Petersburg and 842 versts from Moscow. 1 verst = 1.067m. What is the distance from Moscow to Poltava and from St. Petersburg to Poltava?

2. “However, I just mentioned the district court, but to tell the truth, hardly anyone will look there. This is such an enviable place, God himself protects him ”. How does the mayor explain this statement?

3. His surname is a synonym for the autocratic police regime in the sense of: willful and rude administrator.

4. “Mail” is defined as:

1) “establishment of an urgent message for the forwarding of letters and things”;

2) “place of receiving letters and parcels”.

There are 2 meanings in “The Inspector General”. What other responsibilities did Shpekin have?

5. What rank was Khlestakov?

6. Who is the mayor?

7. What are God-pleasing institutions?

8. Who is a private bailiff?

9. What does incognito mean?

10. What are boots?

11. Who wrote the novel "Yuri Miloslavsky"?

12. What is the “labardan” dish?

13. Who such and what is bad manners?

Last name __________________ First name _________________ Date _____________

0 "style =" border-collapse: collapse; border: none ">

Anton Antonovich Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky - mayor.

* What is the first part of the name "Skvoznik" associated with?

In the Explanatory Dictionary of the Russian Language Ozhegov "Draft is a stream of air blowing a room through openings located opposite each other."

This suggests that the governor is characterized by lawlessness, swagger, complete impunity.

Anna Andreevna

His wife

without a name and patronymic.

Ammos Fedorovich Lyapkin-Tyapkin

Judge.

The surname discloses the principle of his attitude to official affairs "tyap-blooper" and the case is ready, as well as his mental awkwardness, incongruity, clumsiness, tongue-tied speech.

Artemy Filippovich Strawberry

Trustee of charitable institutions.

A careful and cunning man.

Postmaster.

The surname is formed from the word "spy" - he constantly spies, reading other people's letters, unceremonious in his innocence.

Peter Ivanovich Bobchinsky

Peter Ivanovich Dobchinsky

Urban

Replaced only one letter in the surname, in everything they are similar, curious, talkative.

Ivan Alekseevich Khlestakov

"Whipping", "whipping - hitting, hitting with something flexible"

Christian Ivanovich Gibner

County doctor.

The surname is associated with the word "perish".

Private bailiff.

The surname is formed by adding two bases "twirling the ear".

Svistunov

Pugovitsyn

Derzhimorda

Police officers.

The names themselves speak of the actions of these guards.

The people portrayed by Gogol in the comedy "The Inspector General" with surprisingly unprincipled views and ignorance of any reader amaze and seem completely fictional. But in reality, these are not random images. These are the faces typical for the Russian province of the thirties of the XIX century, which can be found even in historical documents.

In his comedy, Gogol raises several very important public issues. This is the attitude of officials to their duties and the implementation of the law. Oddly enough, but the meaning of comedy is relevant in modern realities.

The history of writing "The Inspector General"

Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol describes in his works a rather exaggeration of the images of Russian reality at that time. At the time of the emergence of the idea of a new comedy, the writer is actively working on the poem "Dead Souls".

In 1835, he turned to Pushkin on the idea of a comedy, in a letter he stated a request for help. The poet responds to requests and tells a story when the publisher of one of the magazines in one of the southern cities was mistaken for a visiting official. A similar situation, oddly enough, happened with Pushkin himself at the time when he was collecting materials to describe the Pugachev revolt in Nizhny Novgorod. He was also mistaken for the capital auditor. The idea seemed interesting to Gogol, and the very desire to write a comedy captivated him so much that work on the play took only 2 months.

During October and November 1835, Gogol wrote a complete comedy and a few months later read it to other writers. The colleagues were delighted.

Gogol himself wrote that he wanted to collect everything that is bad in Russia into a single heap and laugh at it. He saw his play as a cleansing satire and a weapon in the struggle against the injustice that existed in society at that time. By the way, the play based on the works of Gogol was allowed to be staged only after Zhukovsky personally made a request to the emperor.

Analysis of the work

Description of the work

The events described in the comedy "The Inspector General" take place in the first half of the 19th century, in one of the provincial towns, which Gogol simply refers to as "N".

The governor informs all city officials that the news of the arrival of the capital inspector has reached him. Officials are afraid of inspections, because they all take bribes, do not work well and in the institutions under their control, a mess reigns.

Almost immediately after the news, the second appears. They realize that a well-dressed man who looks like an inspector is staying at a local hotel. In fact, the unknown is a petty official Khlestakov. Young, windy and stupid. The Governor personally came to his hotel to get to know him and offer to move to his house, in conditions much better than the hotel. Khlestakov happily agrees. He likes this kind of hospitality. At this stage, he does not suspect that he was not mistaken for who he is.

Khlestakov is also introduced to other officials, each of whom hands him a large sum of money, supposedly in debt. They do everything to make the check not so thorough. At this moment, Khlestakov realizes who he was mistaken for and, having received a round sum, is silent that this is a mistake.

Then he decides to leave the city N, having previously made an offer to the daughter of the Governor himself. Joyfully blessing the future marriage, the official rejoices at such a relationship and calmly says goodbye to Khlestakov, who is leaving the city and, naturally, is not going to return to it anymore.

Before that, the main character writes a letter to his friend in St. Petersburg, in which he talks about the embarrassment that happened. The postmaster, who opens all the letters in the mail, also reads Khlestakov's message. The deception is revealed and everyone who gave bribes is horrified to learn that the money will not be returned to them, and there has not been a check yet. At the same moment, a real auditor arrives in the city. Officials are horrified by the news.

Comedy heroes

Ivan Alexandrovich Khlestakov

Khlestakov's age is 23 - 24 years old. Hereditary nobleman and landowner, he is thin, thin and stupid. Acts without thinking about the consequences, has an abrupt speech.

Khlestakov works as a registrar. In those days, this was the lowest-ranking official. At the service he is not present much, more and more often plays cards for money and walks, so his career is not progressing anywhere. Khlestakov lives in St. Petersburg, in a modest apartment, and his parents, who live in one of the villages of the Saratov province, regularly send him money. Khlestakov does not know how to save money, he spends them on all sorts of pleasures, without denying himself anything.

He is very cowardly, loves to brag and lie. Khlestakov is not averse to hitting on women, especially pretty, but only stupid provincial ladies succumb to his charm.

Governor

Anton Antonovich Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky. Aged in the service, in his own way not stupid official, making quite a solid impression.

He speaks carefully and in moderation. His mood changes quickly, his facial features are hard and rough. He performs his duties poorly, he is a fraudster with extensive experience. The Governor profits everywhere, wherever possible, and among the same bribe-takers he is in good standing.

He is greedy and insatiable. He steals money, including from the treasury, and unscrupulously violates all laws. Doesn't even shun blackmail. A master of promises and an even greater master of breaking them.

The Governor dreams of being a general. Ignoring the mass of his sins, he attends church weekly. A passionate card player, he loves his wife, treats her very tenderly. He also has a daughter, who at the end of the comedy, with his own blessing, becomes the bride of the nosy Khlestakov.

Postmaster Ivan Kuzmich Shpekin

It is this character who, in charge of forwarding letters, opens Khlestakov's letter and discovers the deception. However, he is engaged in opening letters and parcels on an ongoing basis. He does this not out of precaution, but solely for the sake of curiosity and his own collection of interesting stories.

Sometimes he does not just read the letters that he especially liked, Shpekin keeps for himself. In addition to forwarding letters, his responsibilities include managing post stations, caretakers, horses, etc. But this is not what he does. He does almost nothing at all, and therefore the local mail works extremely poorly.

Anna Andreevna Skvoznik-Dmukhanovskaya

The Governor's wife. A provincial coquette whose soul is inspired by novels. She is curious, vain, loves to get the best of her husband, but in fact it turns out only in small things.

An appetizing and attractive lady, impatient, stupid and capable of talking only about trifles, but about the weather. At the same time, she likes to chat incessantly. She is arrogant and dreams of a luxurious life in St. Petersburg. The mother is not important, since she competes with her daughter and boasts that Khlestakov paid more attention to her than to Marya. From the entertainment of the wife of the Governor - fortune-telling on the cards.

The Governor's daughter is 18 years old. Attractive in appearance, cutesy and flirtatious. She is very windy. It is she who, at the end of the comedy, becomes Khlestakov's abandoned bride.

Plot composition and analysis

The basis of Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol's play "The Inspector General" is a common anecdote, which at that time was quite widespread. All images of the comedy are exaggerated and, at the same time, believable. The play is interesting in that here all its characters fit together and each of them, in fact, acts as a hero.

The plot of the comedy is the arrival of the inspector expected by the officials and their haste in drawing conclusions, due to which Khlestakov is recognized as the inspector.

Interesting in the composition of the comedy is the absence of a love affair and a love line as such. Here vices are simply ridiculed, which are punished according to the classical literary genre. In part, they are already orders to the frivolous Khlestakov, but the reader understands at the end of the play that even greater punishment awaits them ahead, with the arrival of a real inspector from St. Petersburg.

Through a simple comedy with exaggerated images, Gogol teaches his reader honesty, kindness and responsibility. The fact that you need to respect your own service and comply with the laws. Through the images of the heroes, each reader can see his own shortcomings, if among them there are stupidity, greed, hypocrisy and selfishness.

Gogol began work on the play in the fall. Traditionally, it is believed that the plot was suggested to him by A.S. Pushkin. This is confirmed by the memoirs of the Russian writer VA Sollogub: "Pushkin met Gogol and told him about an incident in the town of Ustyuzhna, Novgorod province - about a passing gentleman who pretended to be a ministry official and robbed all city residents."

There is also an assumption that he goes back to the stories about the business trip of P.P. Svinin to Bessarabia c.

It is known that while working on the play, Gogol repeatedly wrote to Alexander Pushkin about the course of writing it, sometimes wanting to leave it, but Pushkin insistently asked him not to stop working on The Inspector General.

Characters

- Anton Antonovich Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky, mayor.

- Anna Andreevna, his wife.

- Marya Antonovna, his daughter.

- Luka Lukich Khlopov, the superintendent of schools.

- Wife his.

- Ammos Fedorovich Lyapkin-Tyapkin, judge.

- Artemy Filippovich Strawberry, trustee of charitable institutions.

- Ivan Kuzmich Shpekin, postmaster.

- Pyotr Ivanovich Dobchinsky, Peter Ivanovich Bobchinsky- urban landowners.

- Ivan Alexandrovich Khlestakov, an official from St. Petersburg.

- Osip, his servant.

- Christian Ivanovich Gibner, the county doctor.

- Fedor Ivanovich Lyulyukov, Ivan Lazarevich Rastakovsky, Stepan Ivanovich Korobkin- retired officials, honorary persons in the city.

- Stepan Ilyich Ukhovertov, private bailiff.

- Svistunov, Pugovitsyn, Derzhimorda- police officers.

- Abdulin, merchant.

- Fevronya Petrovna Poshlepkina, locksmith.

- Non-commissioned officer's wife.

- bear, the mayor's servant.

- Servant tavern.

- Guests and guests, merchants, bourgeoisie, petitioners

Plot

Ivan Aleksandrovich Khlestakov, a young man with no specific occupation, who rose to the rank of collegiate registrar, follows from St. Petersburg to Saratov, with his servant Osip. He turns out to be passing through a small county town. Khlestakov lost at cards and was left without money.

Just at this time, all the city authorities, mired in bribes and embezzlement, starting with the governor Anton Antonovich Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky, in fear awaited the arrival of the inspector from St. Petersburg. City landowners Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky, accidentally learning about the appearance of the defaulter Khlestakov in the hotel, report to the mayor about the incognito arrival from St. Petersburg to the city.

A commotion begins. All officials and officials bustlingly rush to cover up their sins, but Anton Antonovich quickly comes to his senses and realizes that he needs to bow to the auditor himself. Meanwhile Khlestakov, hungry and unsettled, in the cheapest hotel room, ponders where to get food.

The appearance of the mayor in Khlestakov's room is an unpleasant surprise for him. At first, he thinks that he, as an insolvent guest, was reported by the owner of the hotel. The governor himself is frankly shy, believing that he is talking with an important official in the capital, who has arrived on a secret mission. The mayor, thinking that Khlestakov is an auditor, offers him bribe... Khlestakov, thinking that the mayor is a kind-hearted and decent citizen, takes from him on loan... “I screwed him instead of two hundred and four hundred,” the mayor rejoices. Nevertheless, he decides to pretend to be a fool in order to elicit more information about Khlestakov. “He wants to be considered incognito,” the mayor thinks to himself. - “Okay, let us let the Turus go too, let's pretend we don't know at all what kind of person he is.” But Khlestakov, with his inherent naivete, behaves so directly that the mayor is left with nothing, without losing his conviction, however, that Khlestakov is a "thin thing" and "you need to be on the alert with him." Then the mayor has a plan to give Khlestakov a drink, and he offers to inspect the godly establishments of the city. Khlestakov agrees.

Then the action continues in the mayor's house. Pretty drunk Khlestakov, seeing the ladies - Anna Andreevna and Marya Antonovna - decides to "show off". Drawing in front of them, he tells fables about his important position in St. Petersburg, and, what is most interesting, he himself believes in them. He ascribes to himself literary and musical works, which, due to "extraordinary lightness in thought," supposedly, "in one evening, it seems, he wrote, amazed everyone." And he is not even embarrassed when Marya Antonovna practically accuses him of lying. But soon the language refuses to serve the decently drunken guest of the capital, and Khlestakov, with the help of the mayor, goes to "rest."

The next day he does not remember anything, and wakes up not as a "field marshal", but as a collegiate registrar. Meanwhile, city officials "on a military footing" line up to bribe Khlestakov, and he, thinking that he is borrowing, accepts money from everyone, including Bobchinsky and Dobchinsky, who, it would seem, have no reason to bribe the inspector. And even he begs for money, referring to a "strange case" that "I was completely spent on the road." After seeing the last guest out, he manages to look after Anton Antonovich's wife and daughter. And, although they have known each other for only one day, he asks for the hand of the mayor's daughter and receives parental consent. Further, petitioners break through to Khlestakov, who "beat the governor with their foreheads" and want to pay him in kind (wine and sugar). Only then does Khlestakov realize that he was given bribes, and flatly refuses, but if he was offered a loan, he would take it. However, Khlestakov's servant Osip, being much smarter than his master, understands that nature and money are still bribes, and takes everything from merchants, motivating it by the fact that “the rope will come in handy on the road”. Osip strongly recommends that Khlestakov get out of the city quickly before the deception is revealed. Khlestakov leaves, finally sending his friend a letter from the local post office.

The governor and his entourage take a deep breath. First of all, he decides to "ask pepper" to the merchants who went to complain about him to Khlestakov. He swaggers over them and calls them last words, but as soon as the merchants promised a rich treat for the engagement (and later - for the wedding) of Marya Antonovna and Khlestakov, the mayor forgave them all.

The mayor gathers a full house of guests to publicly announce Khlestakov's engagement to Marya Antonovna. Anna Andreevna, convinced that she has become related to the big bosses of the capital, is delighted. But then the unexpected happens. The postmaster of the local office (at the request of the mayor) opened Khlestakov's letter and it appears from it that he turned out to be incognito a swindler and a thief. The deceived mayor has not yet had time to recover from such a blow when the next news arrives. An official from St. Petersburg who is staying at the hotel demands him to come to him. It all ends with a mute scene ...

Performances